The works that are commonly attributed to Imām Abū Ḥanīfa are:

- Fiqh al-Akbar II (transmitted by Ḥammād b. Abī Ḥanīfa)

- Fiqh al-Akbar II (transmitted by Muqatil ibn Khityan/Abd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī, attribution to Abu Hanifa denied by Dr. Harvey and others)

- Al-ʿĀlim wa al-Mutaʿallim (Anwar Shāh Kashmīrī denies Abu Hanifa attribution)

- Risāla ilā ʿUthmān al-Battī (Anwar Shāh Kashmīrī denies Abu Hanifa attribution)

- Musnad of Abu Hanifa (Falsely attributed to Abu Hanifa by Hadith Fabricator: Abu Muhammad Abdullah ibn Muhammad ibn Yaqub al-Harithi)

The doubt in these attributions isn’t some fringe theory, there are canonical doubts from within the tradition itself from transmitters of hadith, to big sheikhs like Al-Albani. In the 52nd tape of the series Al-Huda wa Al-Nur by the scholar Al-Albani, he was asked about the creed of Imam Abu Hanifa, and whether he had written any books on the subject. He replied:

First: He [Abu Hanifa] did not have a recorded creed.

Second: There is a book attributed to him called Fiqh Al-Akbar. Considering his early period (d. 150 AH), he did not leave behind any books, but he left behind students. The book attributed to him represents the views of those affiliated with Abu Hanifa.“Al-Fiqh al-Akbar is often attributed to Imam Abu Hanifa (may God have mercy on him), but this attribution is not correct.”

Al-Huda wa Al-Nur tape 52 & Jami’ Turath al-Allama al-Albani fi al- ‘Aqidah al-Nu’man Center Edition

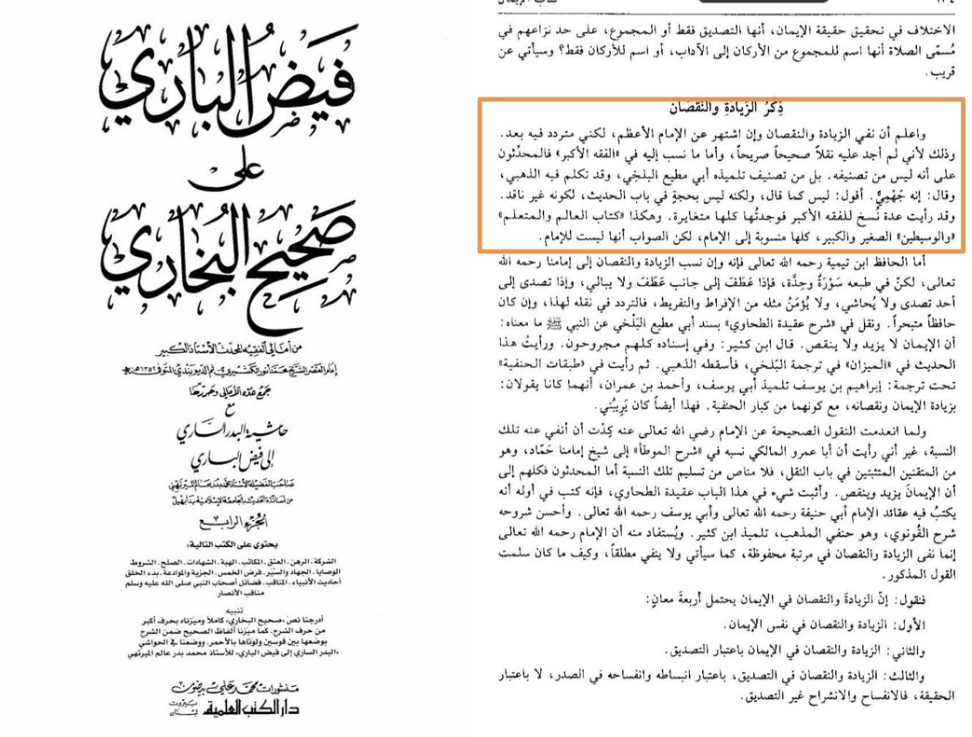

In the following, we have Anwar Shāh Kashmīrī saying that the ‘muhadithun’ (scholars of Hadith) agreed that this book was not by Abu Hanifa. They attributed it to another man, Abu Muṭīʿ al-Balkhi.

Translation:

“Know that the discussion of increase and decrease is not from the writings of the Great Imam (Abu Hanifa), but it was later added to it. This is because no authentic narration has been found from him stating it explicitly. As for what is attributed to him in Fiqh al-Akbar and other writings, it is not from his own authorship but rather from the works of his students. Some of them expressed it in a way that suggests it was dictated by the Imam, while others merely attributed it to him. However, its attribution to him is not accurate.

I have seen several copies of Fiqh al-Akbar, all differing in wording and content. Likewise, the works Al-‘Alim wal-Muta‘allim and Ar-Risalah, both shorter and longer versions, contain various differences. Thus, they cannot be definitively attributed to the Imam, but the correct view is that they are not his own writings.“

Book 1: Fiqh al-Akbar II – Imam Ahmad vs Imam Abu Hanifa (The Anachronisms)

There’s a passage within Fiqh al-Akbar that causes one to be concerned if they adhere to Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal’s circle, or Imam Abu Hanifa’s circle. The issue has to deal with top creedal issues that I will attempt to simplify. The first is about God’s Actions: some believe that God’s actions, like creation, are timeless and pre-eternal, meaning they have always existed and were not limited by time. Others believe that God’s actions happen in time, meaning they started at a specific point.

The second issue is about God’s Speech, specifically the Quran: some believe that God’s Speech, including the Quran, is uncreated and eternal, while others argue that the actual letters or words of the Quran were created at a certain point. This disagreement creates a dilemma for followers, as it forces them to choose between the differing views.

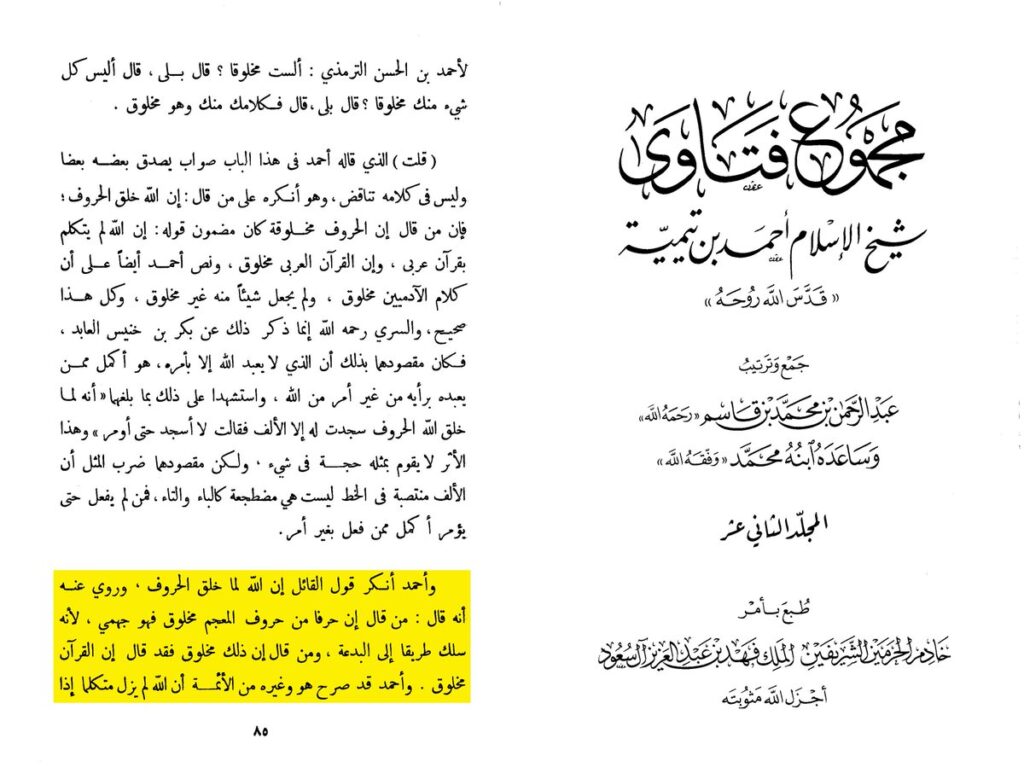

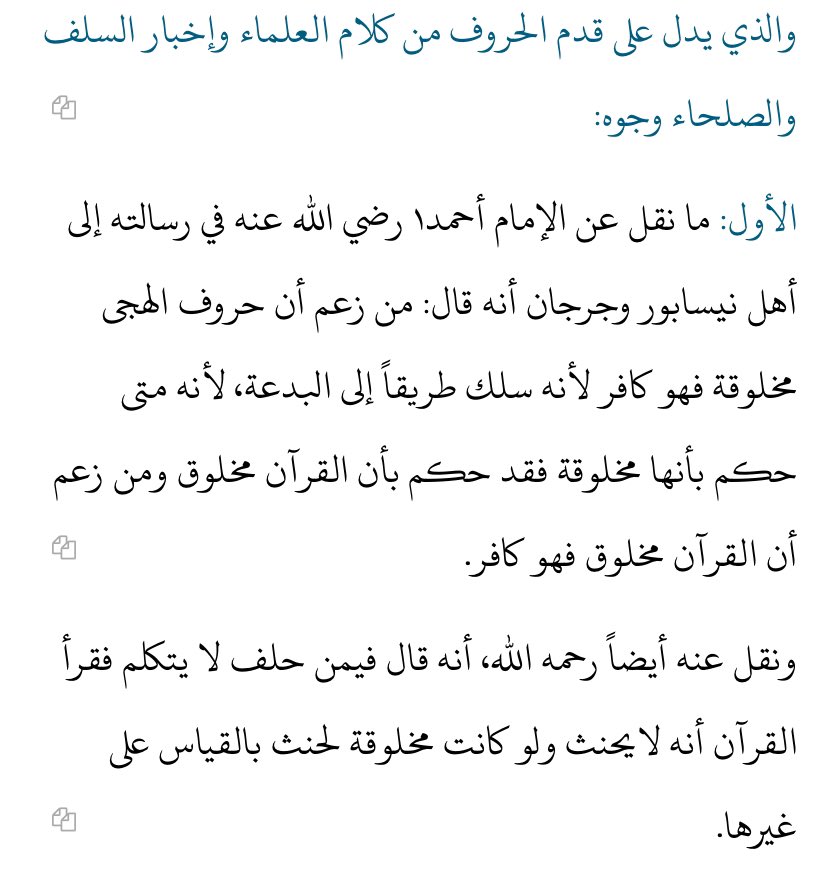

The central issue is whether al-Fiqh al-Akbar is authentic and accurately reflects Imam Abu Hanifa’s theological position, particularly since it contradicts Imam Ahmad’s position on the nature of God’s actions and the status of the Quranic letters. The dilemma is further complicated by the fact that Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal took a strong stance against those who deviated from his views. Specifically, Imam Ahmad declared takfir on anyone who believed that the letters of the Quran were uncreated.

“The spoken word is the speech of God, and it is not created, and the spoken word is created because the spoken word is the result of the reciters acquisition, which is the movement and sound, and the

production of letters, for that is something that the reciter has created, and he has not created the letters of the Quran or its meanings, but rather he has created his pronunciation of it. So the spoken word is a common denominator between both, and for that reason Imam Ahmad did not permit: My spoken word of the Quran is created or not created, because each of the two statements is ambiguous. And God knows best.”

“Ahmad rejected the statement of the one who said that when God created the letters, and it was narrated from him that he said: Whoever says that a letter of the alphabet is created, then he is a Jahmite who has taken a path to innovation, and whoever says that it is created has said that the Quran is created. Ahmad and other imams have stated that God has always been speaking.”

On the other hand, Imam Abu Hanifa, whose teachings are foundational to the Hanafi school, supported the belief in God’s timeless actions and uncreated Speech (assuming Fiqh Al-Akbar is legitimately his). This sharp disagreement between the two imams forces their madhab followers into the difficult position of having to choose between them, especially if they consider al-Fiqh al-Akbar to be an authentic reflection of Imam Abu Hanifa’s theology:

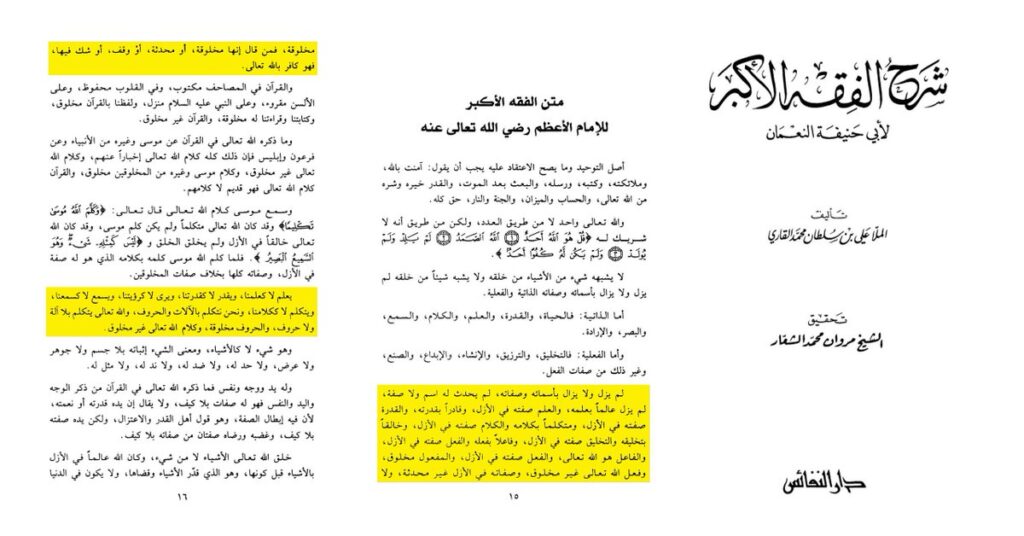

Translation:

He has always existed with His names and attributes; no name or attribute was newly originated for Him. He has always been knowledgeable with His knowledge, and His attribute (of knowledge) is eternal. He has always been powerful with His power, and His attribute of power is eternal. His speech, will, and action are His eternal attributes. Creation, governance, and actions are among the attributes of God the Exalted that have always existed eternally. His actions are not newly originated with a newly created attribute, and His eternal attributes are not created. The actions of God the Exalted are not created, and His attributes are not created.

He knows, but not like our knowledge; He decrees, but not like our decreeing; He sees, but not like our seeing; He hears, but not like our hearing; and He speaks, but not like our speaking. We speak using instruments and letters, while God speaks without instruments or letters. Letters are created, but the speech of God the Exalted is not created.

—

Based on Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal’s strict stance on the theological issues, particularly regarding the Qur’an and God’s attributes, there are specific points in the quotes provided that would fall under the beliefs he considered kufr (disbelief). These points align with the issues where Imam Ahmad declared takfir. Here’s the analysis:

Exact Quotations from Abu Hanifa’s Texts:

- “Creation, governance, and actions are among the attributes of God the Exalted that have always existed eternally. His actions are not newly originated with a newly created attribute, and His eternal attributes are not created.”

- This implies that God’s actions, such as creation and governance, are eternal and pre-eternal. Imam Ahmad strongly opposed this idea, as he believed that God’s actions, including creation, occur within time. For Imam Ahmad, saying actions like creation are eternal implies a fundamental contradiction and would fall under kufr.

- “Letters are created, but the speech of God the Exalted is not created.”

- Imam Ahmad explicitly declared that anyone who says the letters of the Qur’an are created is a disbeliever. This statement from Abu Hanifa aligns with the belief that the letters are created, which Imam Ahmad equated to the Jahmi position and considered to be a deviation worthy of takfir.

Imam Ahmad viewed the claim that actions such as creation are eternal as problematic because it conflicts with his belief that God’s actions occur by His will and power within time. To say creation is eternal would imply an ongoing act of creating, which undermines the temporal nature of the created universe. Imam Ahmad wrote explicitly, “Whoever claims the letters of the Arabic alphabet are created is a disbeliever since he has taken the path of the people of innovation.” Abu Hanifa’s position that “letters are created” directly aligns with this, placing him in the category Imam Ahmad condemned. Essentially, Abu Hanifa’s stance that “Creation, governance, and actions are eternal attributes” would result in takfir by Ahmad (assuming that Fiqh al-Akbar authentically represents Abu Hanifa’s views and that Ahmad would apply his takfir consistently). Additionally, Abu Hanifa’s assertion that “letters are created” would likewise warrant takfir according to Ahmad’s theological framework.

Now, when talking about the differing views between Ahmad and Abu Hanifa, it’s important to point out that these views of ‘Abu Hanifa’ are being extracted from specifically the Fiqh al-Akbar II, transmitted through ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī. There’s another version of the text transmitted from Hammad, that has an opposing view and lacks these theological intricacies that are anachronistically attributed to Abu Hanifa within ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī transmission. This reported dialogue reveals a significant inconsistency in the historical narrative around al-Fiqh al-akbar II. Ḥammād, who supposedly transmitted this creed, displays a distinctly traditionalist approach that avoids deep theological speculation about the Quran’s nature.

It is narrated from al-Ḥasan b. Ziyād, may God have mercy on him, that he said: Ḥammād b. Abī Ḥanīfa and I went to Dāwūd al-Ṭāʾī and something was mentioned, such that Dāwūd said to Ḥammād,

“O Abū Ismāʿīl, whenever a theologian (mutakallim) speaks about something, he hopes that he will be safe from it. Be warned against speaking about the Quran, except that which God, Most High, has said [in it]. I heard your father—that is, Abū Ḥanīfa—say, ‘God has let us know that it is his speech, so whoever takes from what God has informed him has grasped the firmest hand-hold (fa-qad istamsaka bi-l-ʿurwa al-wuthq). Is there, after grasping the firmest hand-hold, anything but falling into perdition?’” Ḥammād then said, “May God reward you friend, how well you speak!”

Al-Ustawāʾī, Kitb al-Iʿtiqd, 167.

This stance contrasts with the sophisticated theological arguments and detailed doctrinal positions we find in al-Fiqh al-akbar II (Muqatil/Bukhari version). The disconnect between Ḥammād’s straightforward, speculation-averse methodology and the text’s complex theological formulations raises important questions about the creed’s true origins and development. Such a disparity suggests that the theological framework presented in al-Fiqh al-akbar II (Muqatil/Bukhari version) likely emerged from a later period when Muslim scholars had become more comfortable engaging in detailed theological discourse about the Quran’s attributes and nature.

The previous points represent a theological issue for those who believe Fiqh al-Akbar II genuinely represents the view of Abu Hanifa. Building on AJ Wensinck’s observation, the theological sophistication and nuanced dialectics present in Fiqh Akbar II suggest it emerged from a later period of Islamic theological development than traditionally attributed. The text’s careful treatment of the Quran’s ontological status – affirming it as uncreated while explicitly rejecting anthropomorphic implications of divine speech through sounds and letters (the battle that Ahmad attempts to refute by blanket takfiring)- reflects the kind of refined theological discourse that became prominent during the 3rd-4th AH/9th-10th AD centuries. Fiqh Al-Akbar II’s sophisticated treatment of divine speech mirrors discussions found in the works of later theologians like al-Ash’ari and al-Maturidi, who developed complex frameworks to explain how God’s speech could be eternal and uncreated while avoiding anthropomorphic implications. This kind of nuanced theological reasoning was largely absent from 8th-century religious discourse, which exposes the anachronistic features.

During Abū Ḥanīfa’s time in the 2nd/8th century, Islamic theological discourse was still in its relatively early stages of development. The refined theological vocabulary and complex conceptual frameworks that we see in Fiqh Akbar II (Muqatil/Bukhari version) had not yet fully evolved. FA II engages with theological questions in ways that clearly reflect the intellectual environment of the 4th/10th century, when Ashʿarī theology was becoming increasingly influential. The text was just too advanced for the time of Abū Ḥanīfa.

Book 1: Fiqh al-Akbar II (FA II) – The Transmission Problem and the Role of ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī

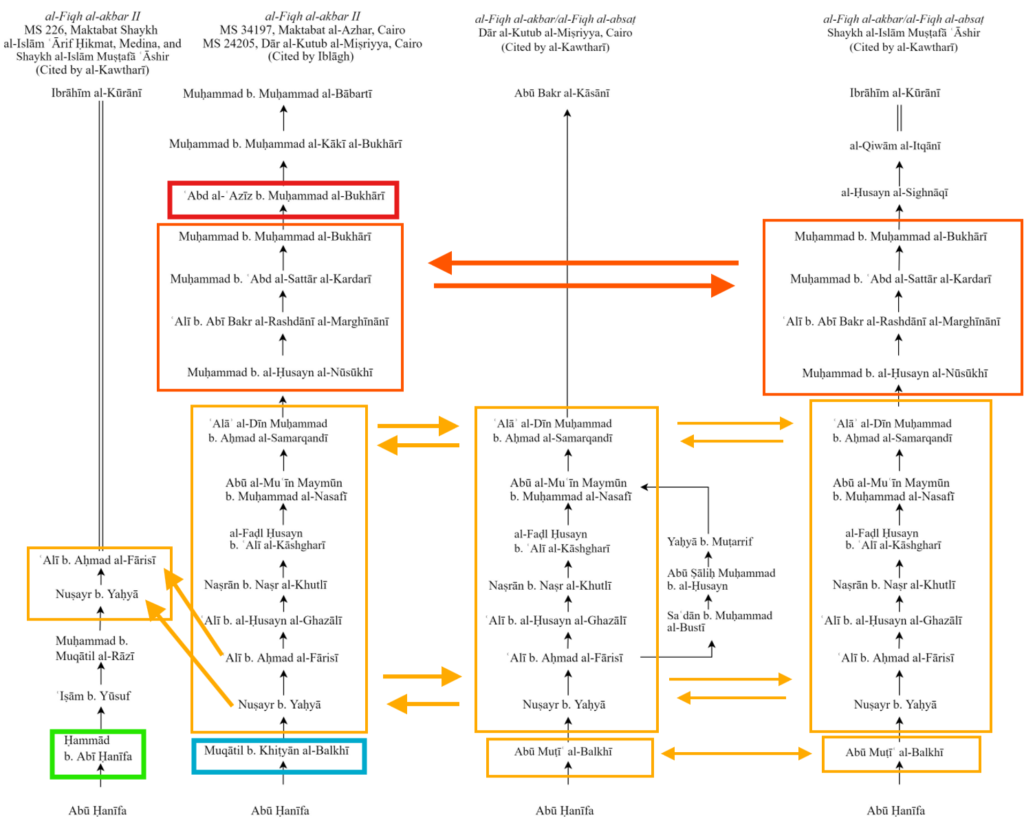

Now, there isn’t just one version of Fiqh al-Akbar. As Anwar Shāh Kashmīrī stated earlier, he said: “I have seen several copies of Fiqh al-Akbar, all differing in wording and content.” The differences are attributed to whose transmitting the work. Dr. Ramon Harvey has demonstrated the isnads for these works:

Additional markings – HadithCritic

One isnad traces back to Imam Abu Hanifa through his esteemed student Abu Muti’ al-Balkhi, another goes through Muqatil ibn Khityan, and the final isnad is through Abu Hanifa’s son, Hammad. The chains of transmission for the three texts in question are largely similar. In particular, the chain for al-Fiqh al-akbar II and al-Balkhī’s al-Fiqh al-akbar are nearly identical. The eleven transmitters between two individuals, Nuṣayr b. Yaḥyā and Muḥammad b. Muḥammad al-Bukhārī, are the same in both texts. This suggests that the texts might have been transmitted together, or one may have influenced the other in its transmission.

The reason why this is dubious is because it seems we have a ‘copy & paste’ isnad between the Muqatil transmission and the Abu Muti transmission. When we look at the earliest mention of this work, we find it in reference to al-Fiqh al-akbar II, by ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī (we put a red box around his name), who came after the sequence of transmitters listed in the chains. This creates suspicion that the transmission chain for al-Fiqh al-akbar II may not be original, but rather copied or derived from the transmission of Abu Muti al-Balkhī’s al-Fiqh al-akbar. Let’s look at the reception of these works and what these scholars mentioned of this work after Abu Hanifa’s passing

- Fihrist of Ibn al-Nadīm– he lists books attributed to Abu Ḥanīfa, including Kitāb al-ʿĀlim wa-l-Mutaʿallim and Kitāb al-Radd ʿalā al-Qadariyya (however, other sources indicate that al-Fiqh al-akbar and al-Radd ʿalā al-Qadariyya are actually different titles for al-Balkhī’s same text, suggesting that these titles refer to the same theological work). Citation: Muḥammad Ibn al-Nadīm, Kitb al-Fihrist li-l-Nadīm, ed. Reżā Tajaddod (Tehran: n.p., 1971), 256.

- Kitab al-Iʿtiqd- The Hanafi author Abū al-ʿAlāʾ al-Ustawāʾī cites material by al-Balkhī quoting verbatim from al-Fiqh al-akbar. Citation: Abū al-ʿAlāʾ al-Ustawāʾī, Kitb al-Iʿtiqd, ed. S. Bāghjawān (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 2005), 125; Abū Ḥanīfa, al-ʿᾹlim wa-l-mutaʿallim, 56. Al-Ustawāʾī, Kitb al-Iʿtiqd, 166–75.

Dr. Ramon Harvey makes a really good argument in regards to the reception of Fiqh al-Akbar:

The span between the sixth/twelfth and early eighth/fourteenth centuries was pivotal for the consolidation of the distinctive tradition of Hanafi theology in Transoxiana that was later known as the Maturidi school. In this section I argue that though Abū Ḥanifa is acknowledged as a key figure in the genealogy of the school and his written theological legacy is cited to varying degrees by its major proponents, the creed al-Fiqh al-akbar II does not make an appearance until it is quoted by ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī (§4), as part of an emerging genre of Hanafi uṣl al-fiqh commentaries.

Mistaken Identity: An Investigation into Abū Ḥanīfa’s

al-Fiqh al-akbar (page 9)

Dr. Harvey makes it clear, that Fiqh al-Akbar II (the transmission with ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī with a red box over it) did not make an appearance until ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī himself quotes it a few centuries after the death of Abū Ḥanīfa. Although Abū Ḥanīfa is recognized as a foundational figure, his work only gained prominence later, particularly through citations by scholars like ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī. This is what we can gather: We have no mention at any point from Abu Hanifa’s death (767 AD), to the first mention by ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bukhārī (d. 1330 AD).

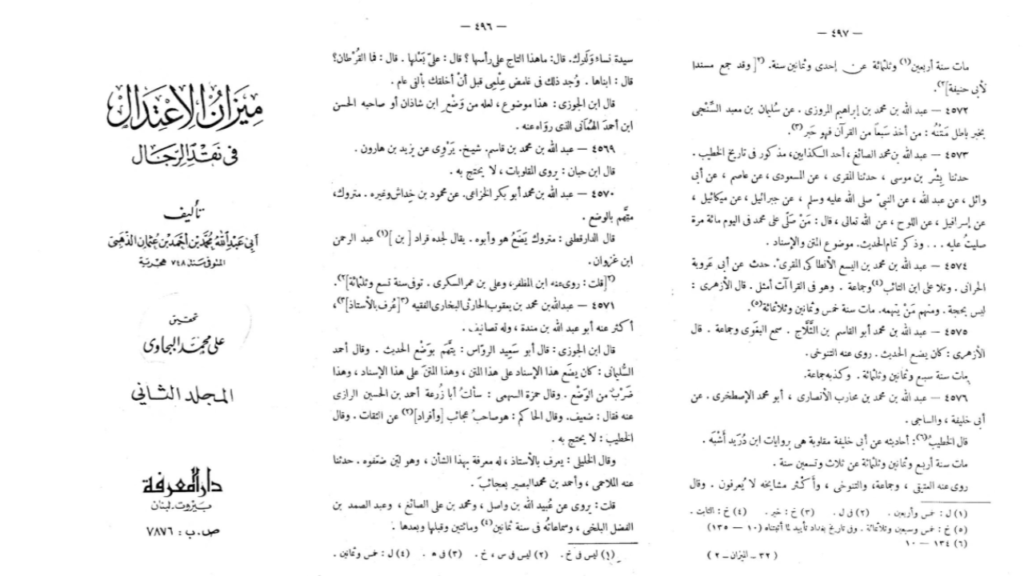

Book 2: Musnad of Abu Hanifa – False and Fabricated Attribution

Abu Muhammad Abdullah ibn Muhammad ibn Yaqub al-Harithi

Known as: The Jurist and “The Professor”

Notable Work: Compiled a Musnad for Abu Hanifa.

Reputation in Hadith Scholarship:

- Abu Abdullah ibn Mundah: Narrated extensively from him and noted that he authored works.

- Ibn al-Jawzi: Cited Abu Saeed al-Rawas, who accused him of fabricating hadith.

- Ahmad al-Sulaymani: Criticized him for mixing up chains of narration with different texts, classifying it as a form of fabrication.

- Hamza al-Sahmi: Reported Abu Zur’ah Ahmad ibn al-Husayn al-Razi’s verdict: Weak. Mentioned that he narrated strange and unique narrations from trustworthy sources.

- Al-Hakim: Recognized him for narrating strange and unique reports, even from trustworthy sources.

- Al-Khatib: Concluded that he “cannot be relied upon.“

- Al-Khalili: While acknowledging his knowledge in the field, described his weaknesses as “mild.”

- Hamza al-Sahmi: Reported asking Abu Zur’ah Ahmad ibn al-Husayn about him, who said: “Weak.”

4572 – Abdullah bin Muhammad bin Ibrahim al-Marwazi

- Narrated a false report through Sulaiman bin Ma’bad al-Sinji.

- Example of fabrication: “Whoever memorizes seven parts of the Quran is a scholar.”

4573 – Abdullah bin Muhammad al-Sa’igh

- Reputation: Labeled as one of the liars.

- Fabricated Hadith Example: A lengthy fabricated chain and narration involving blessings on the Prophet Muhammad and their rewards.

4574 – Abdullah bin Muhammad bin Al-Yasa’ al-Antaki al-Muqri

- Reputation: Accused of unreliability.

- Notable Narration: Excelled in Quranic recitation but was not considered a valid authority.

- Death: Year 385 AH.

4575 – Abdullah bin Muhammad Abu al-Qasim bin al-Thalaj

- Reputation: Accused of fabricating hadiths.

- Notable Narrators: Al-Tanukhi transmitted from him.

- Death: Year 387 AH.

4576 – Abdullah bin Muhammad bin Muharib al-Ansari (Abu Muhammad al-Istakhri)

- Reputation: Known for mixed-up narrations, especially from Abu Khalifah.

- Notable Narrators: Narrated by Al-Atiqi, Al-Tanukhi, and others.

- Death: Year 384 AH at the age of 33.

“ألّف مسندًا للإمام أبي حنيفة وبذل فيه جهدًا كبيرًا، ولكنّه يحتوي على أوابد لم يتفوه بها الإمام، ونُسبت إليه خطأ من قبل أبي محمد. كما كتب كتابًا بعنوان “وهم الطبقة الظلمة على أبي حنيفة”، ولكنني لم أره. وكان يُعتبر شيخ المذهب الحنفي فيما وراء النهر.” “Siyar A‘lam al-Nubala’” by al-Dhahabi (Shams al-Din Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn ‘Uthman al-Dhahabi), volume 15, page 424.

Translation: “He authored a Musnad of Imam Abu Hanifa and put great effort into it. However, it contains peculiarities (awābid) that were not actually said by the Imam, which were mistakenly attributed to him by Abu Muhammad. He also wrote a book titled “The Errors of the Oppressive Class Against Abu Hanifa,” though I have not seen it. He was considered the Sheikh of the Hanafi school in Transoxiana (Ma Wara’ al-Nahr).”

Narrator Dilemma of Musnad of Abu Hanifa

In the Islamic tradition, religious teachings and practices were passed down through chains of narrators, kind of like a game of telephone. The reliability of these narrators was extremely important – think of them as the human hard drives of Islamic knowledge. One of the most important figures in Islamic law was Abu Hanifa (699-767 CE), who founded one of Islam’s major schools of thought. Several scholars collected and compiled his teachings, and they looked carefully at who was passing down his words. Here’s what they found:

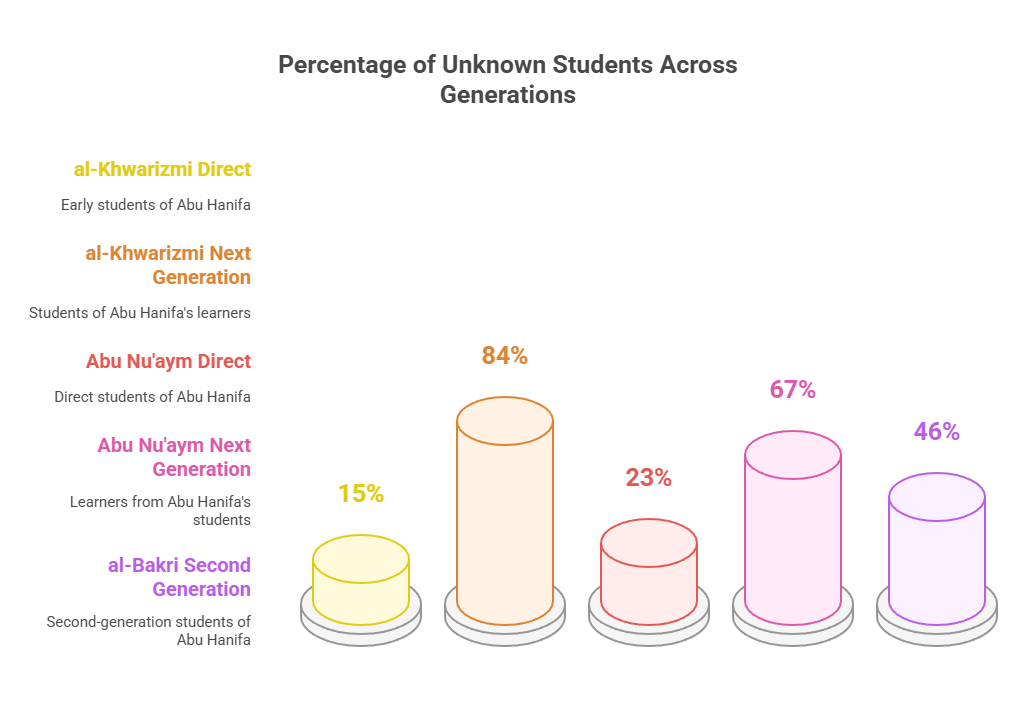

- In al-Khwarizmi’s collection:

- – Among people who directly learned from Abu Hanifa, 15% were “unknown” (meaning we don’t have enough information about who they were).

- However, when looking at the next generation (people who learned from those who learned from Abu Hanifa), a whopping 84% were unknown.

- In Abu Nu’aym’s collection:

- 23% of direct students were unknown.

- 67% of the next generation were unknown

- In al-Bakri’s collection:

- 46% of the second-generation narrators were unknown

To put this in perspective: Over 300 people directly learned and transmitted knowledge from Abu Hanifa About 200 more people were involved in passing on these teachings either before or after. What does this tell us? It’s like a family tree that gets fuzzier as you go further down the generations. While we know quite a bit about Abu Hanifa’s direct students, we know much less about the people who came after them. This created some challenges for Islamic scholars trying to verify the authenticity of religious teachings. Think of it like trying to trace the history of a valuable antique – you might know who the original owner was and maybe the next person who had it, but as time goes on, it becomes harder to track who handled it and how carefully they preserved it. This makes it easier (and more likely) for these later unknown individuals to carefully fabricate chains back to the common individuals that they want to ascribe information to.

Now, there are 5 main points that prove that Abu Hanifa’s followers did not accurately reflect his personal views. These 5 points can be shown as:

- Shift of Key Figures to Baghdad: Abu Hanifa and his prominent students moved to Baghdad, where they did their most influential work. This challenges the notion that the Ḥanafī school was rooted solely in Kufa.

- Scarcity of Kufan Followers: Biographical sources, such as al-Saymari’s dictionary, show a lack of prominent Kufan Ḥanafī scholars after Abu Hanifa’s departure. Among 24 leading figures identified with the Ḥanafī school, only one is definitively Kufan.

- Legal Texts De-emphasizing Kufa: Unlike Maliki legal texts that highlight Medinese origins, early Ḥanafī texts, such as al-Sarakhsi’s Mabsut, do not emphasize Kufa as a central influence.

- Geographic Spread of Hadith: Melchert’s analysis of hadith compilations, like al-Khwarizmi’s Jami’ Masanid al-Imam al-A’zam, shows that while Kufa played a role in transmitting Abu Hanifa’s hadith, Baghdad was far more prominent, especially in later generations.

- “Unknown” Narrators: The high percentage of “unknown” narrators in hadith chains highlights the growing divide between adherents of hadith and ra’y (legal reasoning). This suggests that much of Abu Hanifa’s teaching may have been transmitted outside mainstream Sunni circles.

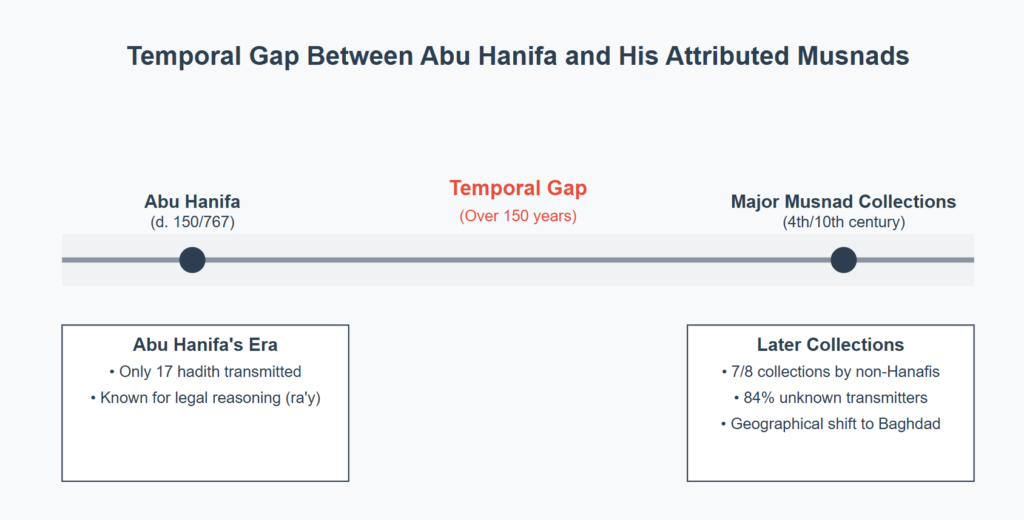

The statistical analysis of transmission patterns further undermines the authenticity of these collections. Al-Khwarizmi’s compilation shows that while 15% of first-generation transmitters were unknown, this number jumps dramatically to 84% in the second generation (Khwarizmi, Jami’, II, 353-588). This pattern is consistently reflected in other sources – Abu Nu’aym’s collection shows 67% unknown second-generation transmitters, while al-Bakri’s biographical work indicates 46% unknown transmitters. This systematic break in transmission chains, coupled with a significant geographical shift from Kufa to Baghdad, suggests a disconnect from Abu Hanifa’s original teaching environment.

The historical context provides additional evidence against the authenticity of these musnads. Ibn Khaldun’s assertion that Abu Hanifa transmitted only 17 hadith reports (Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddima, II, 404) stands in stark contrast to the numerous hadiths attributed to him in later collections. Ibn Abi Shayba’s Musannaf includes a section specifically refuting Abu Hanifa’s doctrine on 125 questions, arguing not that he relied on weak hadiths, but that his positions contradicted hadith altogether (Ibn Abi Shayba, Musannaf, XIII, 80-195). This fundamental contradiction between Abu Hanifa’s known methodological approach, which emphasized legal reasoning (ra’y) over hadith, and the extensive hadith collections attributed to him, strongly suggests later fabrication.

The emergence of these musnad collections primarily in the fourth/tenth century, well over a century after Abu Hanifa’s death (d. 150/767), further weakens their credibility. This temporal gap, combined with the high percentage of unknown transmitters and the predominance of non-Hanafi compilers, suggests a systematic attempt to “traditionalize” Abu Hanifa’s teachings by creating hadith-based supports for his legal opinions. This means a significant departure from his historical role as a rationalist jurist who primarily relied on legal reasoning rather than hadith transmission.

These multiple lines of evidence – the statistical patterns in transmission chains, the historical contradictions, the temporal gap, and the methodological inconsistencies – collectively demonstrate that the musnads attributed to Abu Hanifa largely represent later constructions rather than authentic collections of his teachings. This understanding is crucial for accurately evaluating the development of early Islamic legal thought and the historical relationship between hadith transmission and legal methodology.