When we look at the history of hadith collection, there’s a troubling pattern that’s often overlooked. Government officials frequently used their power to control which Islamic teachings became “official” and which ones were rejected. Scholars who disagreed with rulers often faced harsh punishments.

For example, Ibn Mujahid used political connections to enforce which Qur’anic readings were acceptable. The historical record shows that “those who opposed Ibn Mujāhid’s officially promulgated ‘Canon’ and insisted on following their own standards and criteria were tried, flogged, and coerced into adhering to the consensus.” This wasn’t just a scholarly debate – it was enforcement through violence.

Ibn Mujahid’s Forced Readings

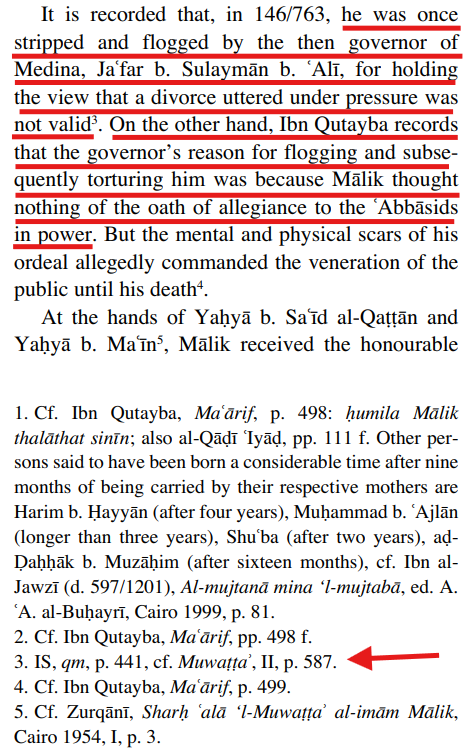

Imam Malik’s Humiliating Punishment

Similarly, Malik ibn Anas was publicly punished by authorities. As the text notes, “he was once stripped and flogged by the then governor of Medina, Ja’far b. Sulaymān b. ‘Alī.” While some claim this was for his position on divorce, “Ibn Qutayba records that the governor’s reason for flogging and subsequently torturing him was because Mālik thought nothing of the oath of allegiance to the ‘Abbāsids in power.” Either way, it shows how political power was used against scholars.

Hanbali Fabricators Advocate For Forced Floggings

This pattern of political interference also appears in accounts related to Ahmad ibn Hanbal. The excerpts mention that “early Hanbali sources assert that Malik ibn Anas… called for the flogging of anyone who said the Qur’an was created.” However, other historical evidence casts doubt on whether Malik actually expressed this opinion at all. This suggests that Ahmad’s followers may have attributed their own views to earlier authorities to gain legitimacy during theological disputes with the state.

Al-Zuhri – an Umayyad stooge

This creates a serious problem for anyone trusting hadith collections. Think about it – if scholars knew they might be beaten or imprisoned for teaching certain things, wouldn’t they be careful about which traditions they passed on? Yaḥyā b. Maʿīn even praised some scholars specifically because “he did not let himself be used by the authorities as Zuhrī had been used by the Umayyads.” This recognition that some scholars were “used by authorities” speaks volumes about the political influence on religious teaching.

Are Hadith Accurate Despite the Caliphal Thumb on The Scale?

Given these historical realities, we must seriously question the reliability of hadith collections. When scholars faced flogging, torture, and imprisonment for expressing views that contradicted political authorities, the collection and preservation of hadith couldn’t have been a purely scholarly enterprise. Some uncomfortable truths emerge. Self-preservation would have led many scholars to self-censor, carefully selecting which traditions to preserve and which to quietly set aside. Rulers actively promoted scholars who supported their political agendas while silencing those who didn’t. On top of this, the practice of attributing newer opinions to respected earlier authorities (as seen with the claims about Malik) makes it difficult to know which teachings genuinely go back to the Prophet and which were later inventions justified by political necessity. The hadith we have today don’t represent the complete religious understanding of early Muslims, but rather the version that survived political filtering.

Politically Charged Hadith:

https://qurantalk.gitbook.io/problematic-sahih-hadith/political-ad-hadith