The Salafi Paradox

Rejection of Scholarly Consensus: Challenging Sunni Orthodoxy

In the last article, we discussed how there was a consensus on the practices of Tawassul and Istighatha through the prophet, saints, and dead. It’s well documented that Salafis abhor such practices and even consider these practices to be acts of shirk. Despite this, the Salafi rejection of Tawassul and Istighatha directly contradicts the consensus (ijma) of Sunni scholarship. Historically, scholars across the four major schools of jurisprudence—Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i, and Hanbali—agreed on the permissibility of seeking intercession and aid through the Prophet and saints.

Here is a short compilation:

Imam al-Nawawī (d. 676 – Shāfiʿī Madhhab)

Translation

The well-known practice is the first method (*), then he returns to his initial position and faces the Messenger of God ﷺ. He seeks intercession through him for himself and asks him to intercede with his Lord, the Glorious and Exalted. Among the best things narrated is what our companions mentioned about the Prophet ﷺ:

That he said: “I was sitting near the grave of the Prophet ﷺ when a Bedouin came and said: ‘Peace be upon you, O Messenger of God. I heard God say: {And if they had, when they wronged themselves, come to you and asked forgiveness of God, and the Messenger had asked forgiveness for them, they would have found God Accepting of Repentance and Merciful} [Qur’an 4:64]. And I have come to you seeking forgiveness for my sins…”

Contributions to Sunni Islam

- Imam al-Nawawi is among the most revered scholars in Sunni Islam. His works, such as Riyadh al-Salihin and his commentary on Sahih Muslim, are staples of Islamic scholarship.

- He was a Shafi’i jurist and a staunch defender of mainstream Sunni practices like visiting graves, seeking intercession (tawassul), and other acts of devotion.

- His 40 Hadith Collection is universally studied and reflects the spiritual and ethical foundations of Islam.

Impact of Losing Him

- Losing Imam al-Nawawi would mean a profound void in Islamic spirituality, jurisprudence, and ethical guidance. His works are foundational to Sunni pedagogy and are used by scholars, laypeople, and jurists alike.

Salafi Dependence on Him

- Salafis rely on Nawawi’s hadith commentaries for their legal and theological frameworks. Yet, Imam al-Nawawi explicitly supported practices like tawassul and rejected the rigid literalism that Salafis promote. By condemning these practices, Salafis effectively undermine the contributions of one of the most respected scholars in Sunni Islam.

al-Jazarī, Shams al-Dīn (d. 711 – Shāfiʿī Madhhab)

Translation

Shams al-Din al-Jazari, the commentator on the “Minhaj” in the principles of jurisprudence regarding Shaykh Taqi al-Din Ibn Taymiyyah, states: It is said about him (Ibn Taymiyyah) that he declared, “It is not permissible to seek assistance from the Messenger of God ﷺ, because seeking assistance is exclusive to God—Glorified and Exalted—being one of His specific attributes and exclusive rights (*). Thus, it cannot be attributed to others, just as worship cannot.”

The elaboration of the mentioned argument: It is said that one must examine the true nature of “seeking assistance” (استعانة)—what it means. It involves seeking support and extraction (**). Then, we find in this case that the Israelite sought assistance from Moses, called for his aid, and cried out to him, as explicitly mentioned in these verses. This is an example of a created being seeking assistance from another created being. Moses approved of this and did not object to it. Similarly, Muhammad ﷺ did not object to this when this verse was revealed to him (*): This implies that it was an acknowledgment from God—Glorified and Exalted—and His Messenger of the permissibility of seeking assistance from a created being.

Contributions to Sunni Islam

- Shams al-Dīn al-Jazarī was a towering scholar of usul al-fiqh (principles of Islamic jurisprudence) and theology. His works elucidated complex theological concepts, often defending the legitimacy of practices such as tawassul (seeking intercession) and istighatha (calling upon the Prophet or pious individuals for aid).

- He was part of the broader Sunni scholarly tradition that balanced jurisprudence and spirituality, often engaging in debates with extremist views that deviated from mainstream Islam.

Impact of Losing Him

- Sunni jurisprudence and theology would lose an important advocate for intellectual rigor and the defense of practices deeply embedded in Islamic tradition. His contributions counteracted rigid literalism and ensured that Islamic law remained practical and spiritually nourishing.

Salafi Dependence on Him

- Salafis indirectly benefit from his jurisprudential methodologies, which shaped much of classical Sunni thought. However, by labeling practices like tawassul as shirk, Salafis reject positions he staunchly defended, distancing themselves from his theological legacy.

Ibn al-Jazarī, Shaykh al-Qurrāʾ(d. 833)

Translation

18 – And that he should not raise his gaze towards the sky (mentioned in Muslim and others).

19 – And that he should ask Allah Almighty by His most beautiful names and highest attributes (mentioned in Muslim, Tirmidhi, and others).

20 – And that he should avoid affected and contrived rhyming in supplication (mentioned in Muslim).

21 – And that he should not overly elaborate or force embellishment in his words (mentioned in Muwatta).

22 – And that he should seek intercession with Allah Almighty through His Prophets (as mentioned in Bukhari, Darimi, and Muslim) and the righteous among His servants.

Contributions to Sunni Islam

- Ibn al-Jazarī is the undisputed authority in Quranic sciences and tajwid (rules of Quranic recitation). His monumental works, such as al-Nashr fi al-Qira’at al-‘Ashr and Tayyibat al-Nashr, codified and preserved the ten authentic modes of Quranic recitation (qira’at).

- He ensured that the oral transmission of the Quran remained uniform, accessible, and accurately transmitted.

- His works are studied globally in every Islamic institution, regardless of sect or school.

Impact of Losing Him

- Without Ibn al-Jazarī, the proper transmission and standardization of Quranic recitation would have been at significant risk. The beauty, precision, and integrity of the Quran’s oral tradition would have suffered fragmentation. Sunni Islam, which prides itself on the preservation of the Quran, owes an enormous debt to his scholarship.

Salafi Dependence on Him

- Salafis heavily depend on Ibn al-Jazarī for Quranic recitation, as his methodologies form the foundation of the global recitation standard.

- Ironically, Ibn al-Jazarī also supported traditional Sunni practices, including certain forms of tawassul, which many modern Salafis reject. By condemning these practices, Salafis unwittingly create a theological rift with a figure they otherwise revere.

By opposing these well-established practices, the Salafi movement directly challenges the historical foundation of Sunni orthodoxy. This rejection not only isolates them from the majority of Muslims but also raises questions about their adherence to one of the core principles of Islamic jurisprudence: following the consensus of the Muslim community. If ijma is a defining feature of Sunni Islam, then the Salafi stance represents a significant deviation from traditional Islam.

More in the compilation: Gitbook

The Contradiction of Borrowed Jurisprudence – The Salafi Dilemma

Despite the Salafis vocal rejection of Tawassul and Istighatha, Salafis paradoxically depend on the legal rulings of scholars from the very Sunni schools that upheld these practices. The four madhhabs, whose legal structures Salafis frequently rely upon, permitted Tawassul and Istighatha as legitimate acts of devotion.

This reliance on scholars whose views they reject as “idolatrous” creates a profound inconsistency in Salafi theology. How can Salafis simultaneously condemn Tawassul and Istighatha as shirk while drawing upon the legal rulings of jurists who practiced and endorsed these acts? This selective reliance reveals a critical flaw in Salafi methodology, exposing their inability to reconcile their theological positions with the broader Sunni tradition.

Rejection of Scholarly Consensus: Challenging Sunni Orthodoxy

The Salafi rejection of Tawassul and Istighatha directly contradicts the consensus (ijma) of Sunni scholarship. Historically, scholars across the four major schools of jurisprudence—Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i, and Hanbali—agreed on the permissibility of seeking intercession and aid through the Prophet and saints.

- Imam al-Taqī al-Subkī argued emphatically that no scholar prior to Ibn Taymiyyah had questioned the validity of these practices, emphasizing their entrenched place in Sunni orthodoxy.

- Najm al-Dīn al-Tūfī noted that the generation of scholars in his time, as well as those before and after, upheld the permissibility of Istighatha. This further establishes that the rejection of these practices was a theological anomaly introduced by Ibn Taymiyyah.

- Early Islamic jurists such as Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal—often cited as an authority by Salafis—are documented to have approved of Tawassul in their legal and theological works.

By opposing these well-established practices, the Salafi movement directly challenges the historical foundation of Sunni orthodoxy. This rejection not only isolates them from the majority of Muslims but also raises questions about their adherence to one of the core principles of Islamic jurisprudence: following the consensus of the Muslim community. If ijma is a defining feature of Sunni Islam, then the Salafi stance represents a significant deviation from traditional Islam.

No Excuse – Salafi Sheikh Bin Baz

The Salafi claim that Tawassul and Istighatha constitute shirk akbar (major polytheism) has radical implications for the Islamic community as a whole. If these practices are indeed shirk, as Salafis assert, then the overwhelming majority of Muslims throughout history—including many of Islam’s greatest scholars, saints, and jurists—would be considered disbelievers.

- Figures like Imam al-Nawawi, Imam al-Ghazali, Imam al-Taqī al-Subkī, and countless others who upheld and practiced Tawassul and Istighatha would, under Salafi logic, fall into the category of polytheists.

- By extension, the followers of the four Sunni madhhabs (~ 2 Billion Muslims), who form the bulk of the global Muslim population, would also be implicated in this accusation of shirk.

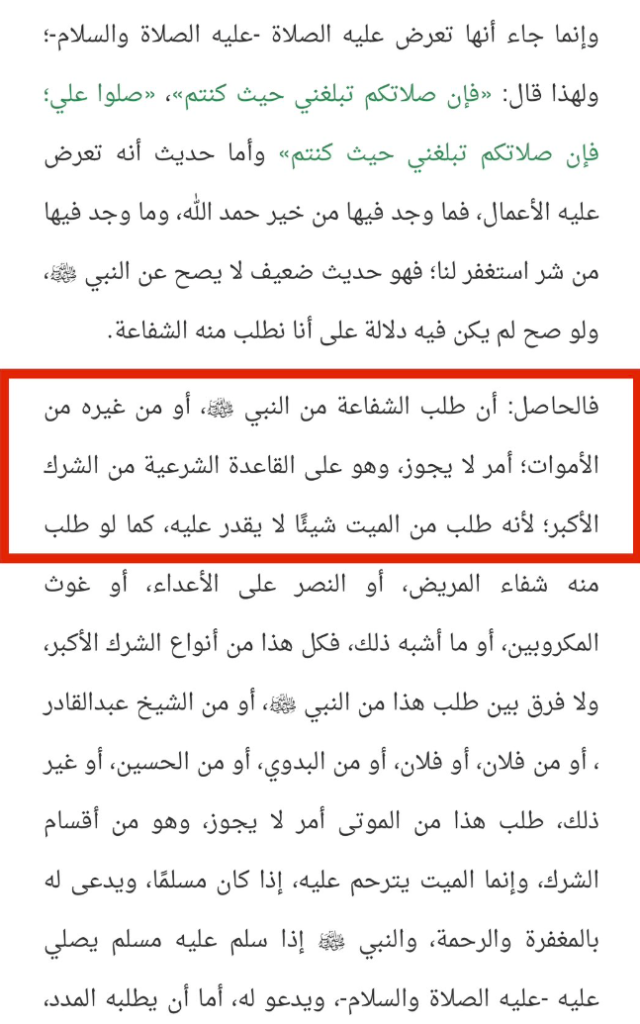

Translation:

“In summary: Requesting intercession from the Prophet ﷺ or from others among the deceased is not permissible. This is based on the established Shariah principles that classify such actions as major shirk. This is because requesting something from the deceased, which they cannot accomplish, is akin to attributing divine powers to them. For example, if one were to request healing for the sick, victory over enemies, relief from distress, or anything of a similar nature, it falls under the types of major shirk.

There is no difference in this matter whether the request is made to the Prophet ﷺ, Shaykh Abdul Qadir, or anyone else such as so-and-so, al-Badawi, al-Husayn, or others. Requesting such aid from the deceased is not permissible. It is among the categories of shirk, as the deceased cannot respond to or fulfill such requests.

Instead, one should pray for mercy and forgiveness for the deceased and invoke Allah’s blessings upon them if they were Muslim. As for the Prophet ﷺ, if one offers prayers upon him (peace and blessings be upon him), it is an act of worship that is prescribed.”

Bin Baz

Question:

“Who are those excused for their ignorance? Can a person be excused for their ignorance in matters of Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), `Aqidah (creed), and Tawhid (monotheism)? What is the role of scholars in this regard?“Answer:

“Being excused due to ignorance is a matter that needs elaboration, and not everyone can be excused due to their ignorance. The excuse of ignorance cannot be applied to teachings of Islam made clear by the Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him) and the Qur’an, especially in matters related to `Aqidah (creed) and the principles of religion … Similarly, someone may claim they do not know it is forbidden to do what Mushriks (those who associate others with Allah in His Divinity or worship) do, who visit the graves and call upon idols, supplicate, slaughter, or vow for them. Other Mushriks slaughter animals for idols, planets, trees, or stones. They may seek treatment or victory from the dead people, idols, jinn, angels, prophets, or anyone. All of these practices are well-known to be major Shirk. Allah shows this fact in the Glorious Qur’an … However, violating the principles of `Aqidah, the pillars of Islam, and the well-known prohibited acts are not to be excused on the plea of ignorance.”

More:

By Sheikh Abdul Aziz bin Baz

By Sheikh Abdul Aziz Al-Rajhi

Sheikh Abdul Aziz bin Baz explicitly holds the position that ignorance is not a valid excuse for engaging in major shirk when the foundational teachings of the religion, particularly strict monotheism, are well-established and accessible. By this standard, past scholars who advocated practices such as tawassul (seeking intercession) and istighatha (seeking help) through the Prophet Muhammad or other righteous individuals would not be excused, as these actions fall under what bin Baz categorizes as clear acts of major shirk. According to bin Baz, matters of monotheism are self-evident and integral to the faith, making any deviation from them inexcusable for individuals living within an Islamic context or who had access to the Quran.

This stance effectively invalidates the contributions and theological positions of those scholars who endorsed such practices, even if their intentions were rooted in reverence for the Prophet or the righteous. Bin Baz’s rigid framework places them in direct violation of the principles of monotheism, as understood by the Salafi methodology. Consequently, this view dismisses centuries of scholarship that permitted these practices, labeling them as incompatible with pure monotheism and undermining the legitimacy of their positions in the eyes of Salafi thought. Such a perspective creates a sharp dichotomy between Salafi interpretations of the religion and the broader Sunni tradition, which historically accommodated diverse opinions on these matters.

Conclusion: A Movement at Odds with Itself

The Salafi rejection of Tawassul and Istighatha reveals a series of paradoxes and contradictions that challenge the coherence of their theological framework. By opposing practices upheld by the majority of Sunni scholars, Salafis isolate themselves from the broader Muslim community and undermine the very tradition they claim to uphold. Their reliance on jurisprudential traditions they deem idolatrous, coupled with their alienation of the majority of Muslims, highlights the intellectual inconsistencies at the heart of their movement.

Far from representing a return to “pure” Islam, Salafism emerges as a movement defined by selective interpretations, theological rigidity, and a rejection of the rich diversity of Islamic tradition. In their attempt to eliminate perceived innovations, Salafis risk creating a theology that is both inconsistent and deeply divisive, alienating them from the historical and contemporary Muslim ummah.