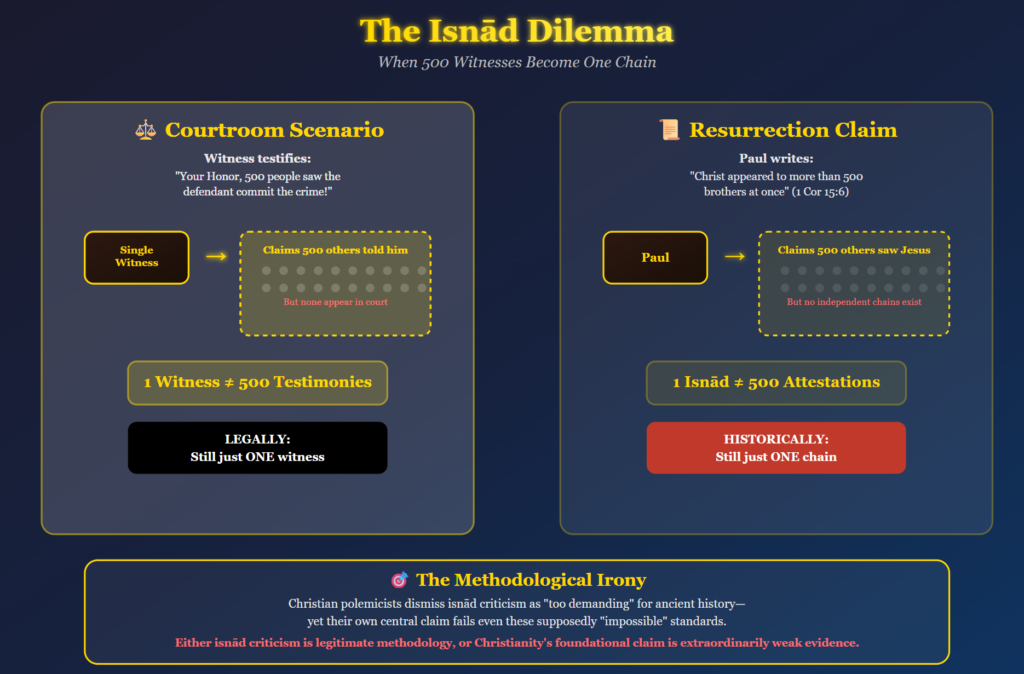

In Christian apologetics, perhaps no claim is more famous than the claim that more than 500 people witnessed the resurrected Christ. Based on 1 Corinthians 15:6, apologists advocate that this is powerful historical evidence; a collective testimony that could not possibly be invented or overlooked. However, using the critical apparatus of isnād criticism within Islamic hadith studies, this seemingly impressive claim ultimately reveals an internal flaw that fatally undermines its evidential significance.

The underlying principle is straightforward and yet impactful. The impact of a historical claim is not based on how many numbers it mentions, but on the number of independent and traceable chains of transmission (asānīd) back to the original event. This approach requires us to be clear about what constitutes multiple attestation and what is merely a representation of multiple attestation.

The “500 Witnesses”

“Then he appeared to more than five hundred brethren at one time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep” – 1 Corinthians 15:6 (RSVB)

At face value, this seems compelling testimony. Paul mentions ‘more than 500’, suggesting that many were still alive at the time of his writing, and presents this as an established fact. However, as a quick analysis will reveal, there is a major issue of significance here: the whole narrative rests on Paul as the one narrator, who was not a witness to the event.

From a chain-of-transmission perspective, what we have is extraordinarily thin:

- Paul → Corinthian Christians → manuscript tradition → us

This represents exactly what hadith critics call a khabar wāḥid (solitary report)—a single-chain transmission that, regardless of what numbers it contains, cannot achieve the epistemic certainty of mutawātir (mass-transmitted) reports.

The system of isnād criticism understands that verification of a past event requires an independent chain of transmission for each independent corroboration. It does not rely on verification merely for a single witness. Similarly, just because a narrator claims the existence of extensive witnesses, it does not create more forms of an isnād; it still shows they claim only one isnād, and only that one isnād has been presented to us. We can consider this with some examples from ḥadīth literature. If al-Zuhrī, alone, transmitted that the Prophet gave a sermon to 10,000 people during Hajj, and only the one paramout witness, al-Zuhrī, transmitted that saying, then we have only reported hearing of one isnād, or only al-Zuhrī’s chain. For this to obtain mutawātir status, we would need independent chains, with separate testimonies from at least two (or other primary witnesses with two chains) who were there and transmitted it independently from their own lines of transmission.

The same principle applies to Paul’s claim. Even if we accept his sincerity, we have:

- One narrator (Paul)

- Making one claim (500 people witnessed the resurrection)

- Through one chain of transmission

This is definitionally not 500 independent attestations.

Imagine appearing before a judge with the following testimony:

“Your Honor, I have 500 witnesses who will testify that the defendant committed this crime.”

The judge asks, “Where are these 500 witnesses?”

You respond, “Well, they’re not here, but I’m telling you that 500 people told me they saw it happen.”

Any competent judge would recognize this as one witness (you) making a claim about 500 others. Without the actual testimony of those 500 individuals, delivered through independent channels, the court has only your word that they exist and made such claims. This is precisely the situation with 1 Corinthians 15:6. We have Paul’s testimony about 500 others, but no independent access to those alleged witnesses through separate chains of transmission.

Paul’s Letters (50s-60s CE): Our earliest sources, but Paul himself claims no direct witness to the resurrection appearances beyond his own Damascus road experience.

The Gospels (70s-100s CE): Later sources that, while containing appearance narratives, show significant variation in details—exactly what hadith critics would expect when accounts develop over time through community transmission rather than rigorous isnād preservation.

External Sources: Virtually non-existent from the first century.

In hadith terminology, this would classify the resurrection accounts as āḥād (solitary) rather than mutawātir (mass-transmitted). The numerical claims within these accounts do not change their fundamental status as single-chain reports.

When we apply these standards to the “500 witnesses” claim:

- Multiple chains: Absent (we have only Paul’s report)

- Named narrators: Paul names no individual witnesses from the 500

- Continuous transmission: Broken – no direct chain from any of the 500 to Paul

- Reliability assessment: Impossible without named sources to evaluate

Paul demonstrates a continued history of deception, indicating he is a narrator that cannot be trusted. When James and the elders of Jerusalem confronted Paul about teaching Jews to abandon the Law of Moses (Acts 21:17-26), Paul chose not to disclose his teachings, decided to take a Nazarite vow that demonstrated a commitment to the Law, and participated in the temple purification rites—despite saying in private to Gentile audiences that both the rites and the Law were obsolete. This was a systematic deception of religious authorities who had legitimate concerns with his innovations. Of even greater consequence is Paul’s overt claim of strategic falsehood as a means of production. In 1 Corinthians 9:20-22, he states he was becoming “all things to all people,” using various definitions of Law observance to Jews and nothing to Gentiles, by changing, in some cases, fundamentally, religious beliefs based on his audience. Even more telling about his view of himself, in Romans 3:7-8, Paul builds a case for lying if it brings about, in his belief, glory for God. He asks rhetorically why he should be condemned when his lies are for the right causes?

5 But if our unrighteousness brings out God’s righteousness more clearly, what shall we say? That God is unjust in bringing his wrath on us? (I am using a human argument.) 6 Certainly not! If that were so, how could God judge the world? 7 Someone might argue, “If my falsehood enhances God’s truthfulness and so increases his glory, why am I still condemned as a sinner?” 8 Why not say—as some slanderously claim that we say—“Let us do evil that good may result”? Their condemnation is just! – Romans 3:5-8

These aren’t isolated incidents. It reveals a systematic dishonesty that would immediately disqualify Paul as a reliable narrator under any historical methodology. A narrator who admits to strategic deception, demonstrates contradictory behavior across audiences, and provides multiple contradictory accounts of foundational experiences simply cannot serve as the sole source for extraordinary claims like “500 witnesses.” The evidential house of cards collapses when built on such compromised foundations.

The striking thing about this isnād analysis is not that it shows the resurrection accounts to be weak; rather, it is that a technique Christian polemicists regularly dismiss as historically invalid cannot even be used to validate Christianity’s most central claim. If isnād analysis is as flawed and excessively demanding as Christian critics insist (and they are correct about its flaws), then the resurrection accounts should have little, if any, difficulty passing it in practice. They don’t. This leaves Christian apologists with the unenviable task of either admitting they have accepted an unassailable historical methodology (thereby revealing their critique of Islamic transmission to be deeply misguided) or insisting the method’s standards are wholly unrealistic while simultaneously being unable to explain why Christianity’s central historical claim fails to meet even these supposedly “impossible” standards.

The “500 witnesses” testimony of 1 Corinthians 15:6 (if it can be considered evidence at all) is, under isnād analysis, not a deliverable or overwhelming point of historical proof, but rather the very definition of a single-source, unverifiable assertion that any rigorous historical methodology (Islamic, Christian, or secular) should treat with skepticism. The methodology did not fail; it worked exactly as intended, exposing the thinness of the evidence behind the impressive-sounding number of witnesses.