Established Practices: How Worship Was Known Without Hadith

One of the most common complaints thrown at Submitters revolves around the question, “If the Quran is fully detailed, then where does it show us how to pray?” Many traditional Muslims assume this proves that Hadith is essential. However, this objection ignores a key point: the Quran was not revealed in isolation. It was revealed to people who already had basic worship practices in place. This included the Contact Prayers (ṣalāt). These were not new rituals invented by the Prophet Muhammad. They came from a well-established tradition passed down from Prophet Abraham through his son Ishmael, and continued through Abraham’s descendants. This is what is referred to as established practice.

It means the Quran speaks about practices that the people were already familiar with and actively performing. Because of this, the Quran does not need to give detailed, step-by-step instructions for rituals like prayer. These rituals were already known to the community. Instead, the Quran focuses on correcting corruptions, removing idol worship, and turning people back to the worship of God alone. That was the true mission of the Quran; not to invent new religious practices, but to purify existing ones and restore them to their proper monotheistic foundation.

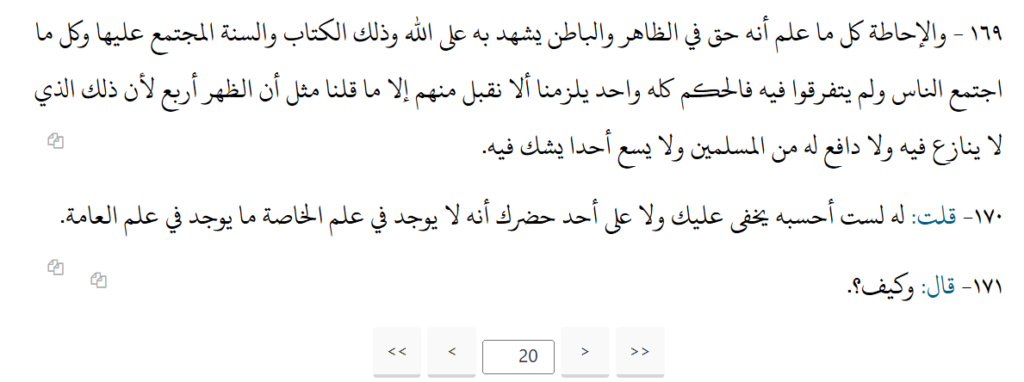

Interestingly, while reading Kitāb Jāmiʿ al-ʿIlm by al-Shāfiʿī, I came across a passage that shows he, too, acknowledges this idea of established practice. In his debate with a supposed Quranist, he makes the following point:

١٦٩ – والإحاطة كل ما علم أنه حق في الظاهر والباطن يشهد به على الله وذلك الكتاب والسنة المجتمع عليها وكل ما اجتمع الناس ولم يتفرقوا فيه فالحكم كله واحد يلزمنا ألا نقبل منهم إلا ما قلنا مثل أن الظهر أربع لأن ذلك الذي لا ينازع فيه ولا دافع له من المسلمين ولا يسع أحدا يشك فيه.

169 – And comprehensive knowledge includes everything that is known to be true outwardly and inwardly, and which bears witness to God. That includes the Book, the Sunnah upon which there is consensus, and everything the people have agreed upon without disagreement. The ruling in all of this is unified, and we are required not to accept from them anything except what we have said—such as that Ẓuhr is four [rakʿahs]—because this is something about which there is no dispute, no rejection from any Muslim, and no one is allowed to doubt it.

١٧٠- قلت: له لست أحسبه يخفى عليك ولا على أحد حضرك أنه لا يوجد في علم الخاصة ما يوجد في علم العامة

170 – I said to him: I do not think it is hidden from you, nor from anyone present, that there is nothing in the knowledge of the elite that is not also found in the knowledge of the general public.

١٧١- قال: وكيف؟

171 – He said: How so?

١٧٢- قلت: علم العامة على ما وصفت لا تلقى أحدا من المسلمين إلا وجدت علمه عنده ولا يرد منها أحد شيئا على أحد فيه كما وصفت في جمل الفرائض وعدد الصلوات وما أشبهها

172 – I [al-Shāfiʿī] said: The knowledge of the general public is as you described. You do not meet any Muslim without finding that he possesses this knowledge, and no one among them rejects it from another—such as the basic obligations, the number of prayers, and things like that.

These words from al-Shāfiʿī demonstrate that even within early traditionalist thought, there was an awareness that some religious practices were transmitted through common knowledge. He refers to things that were so well-known that no one among the Muslims questioned them—like the number of daily prayers—not because of hadith chains, but because they were part of the lived religion of the people.

2:128–129: Abraham and Ishmael ask God to show them their rites and send a messenger from among them.

2:183: “Fasting is prescribed for you, as it was prescribed for those before you…”

2:197: Pilgrimage is described with minimal instruction.

5:6: Wudu (ablution) is described.

22:26–27: Abraham was commanded to proclaim the pilgrimage.

16:123: “Then We inspired you [Muhammad] to follow the religion of Abraham.”

The Quran repeatedly refers to core acts of worship (prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, and zakat) as established rites that were already known and practiced by the community long before the Prophet Muhammad. For example, in 2:128–129, Abraham and Ishmael ask God to show them their rites and send a messenger from among their descendants. Fasting is described as a prescription “as it was prescribed for those before you” (2:183). Pilgrimage is mentioned with only minimal instruction (2:197), and ablution (wudu) is described (5:6). God commands Abraham to proclaim the pilgrimage (22:26–27), and Muhammad is told to follow the religion of Abraham (16:123).

These verses show that the Quran assumes the existence of an inherited, established practice of worship. It neither invents new rituals nor details every aspect of them because they were already well-known to the people. This understanding is not unique to Submitters but is recognized even by some early traditional scholars.

For instance, Imām Mālik ibn Anas, the founder of the Mālikī school of law, places great authority on the practice of the people of Madinah (ʿamal ahl al-Madīnah). He considered their established communal practice to be a binding proof, sometimes even stronger than solitary hadith reports. As one classical explanation puts it:

[The practice of the people of Madinah] is one of the foundations of Mālik’s school, as previously mentioned. And the practice of the people of Madinah, if it occurs regarding an issue and their scholars agree upon it, Mālik declares it authoritative and gives it precedence over analogy, even over authentic hadith. Rather, the practice of the majority among them is taken as a proof, and he gives it precedence over a report, and he gives it precedence over a solitary report, because to him it is stronger than it…

مسار الصفحة الحالية:

فهرس الكتابترجمة سادسهم الإمام العلم إمامنا وإمام دار الهجرة وأمام الأئمة مالك بن أنسعمل أهل المدينة

This principle of maʿlūm min al-dīn bi-ḍ-ḍarūra explains why core religious practices such as prayer, fasting, zakāt, and pilgrimage are universally accepted and expected to be known by the Muslim community without needing detailed textual proof every time. It also clarifies the stance of classical scholars like al-Nawawī and Ibn Taymiyyah, who emphasize that denying such established knowledge is a serious matter, but genuine ignorance may be excused under certain circumstances.

“Clear and mass-transmitted rulings—whether obligations or prohibitions—whose knowledge is widespread among all Muslims, are considered maʿlūm min al-dīn bi-ḍ-ḍarūra (known of religion by necessity). No Muslim is permitted to be ignorant of these. Whoever denies them is considered a disbeliever according to consensus among scholars. However, genuine ignorance is excused in cases of isolation or recent conversion, as assigning blame beyond capacity is unjust.”

Together with Mālik’s emphasis on the established practice of Madinah, this shows that early Islamic scholarship recognized a clear distinction between universally known religious duties and more specialized knowledge requiring explicit textual evidence. A key misunderstanding among many traditionalists is the assumption that all aspects of worship must be learned directly from hadith collections or the Quran in totality. However, Islamic legal tradition recognizes another vital source of religious guidance: the established practice (ʿamal) of the community.

ʿAmal refers to the collective actions and rites, acknowledged and practiced regularly by any community, especially the collective of early Muslims in Madinah. Because of the frequency and depth of social practice, it acts as a purposeful transmission of religious knowledge. It is a social practice reflecting the inherited legacy from Prophet Muhammad and the previous Prophetic traditions, maintained through social action, not just reports.

Imām Mālik and other classical scholars explicitly held that ʿamal ahl al-Madīnah carries legal weight and can even take precedence over solitary hadith reports. This means that the way the people of Madinah regularly performed prayer, fasting, zakāt, and pilgrimage is itself a proof of the correct method.

This understanding aligns perfectly with the Submitter view that the Quran, being fully detailed and sent to a community already familiar with its rites, does not require hadith to teach the fundamental practices of worship. Instead, the community’s inherited ʿamal embodies the authentic tradition passed down from Abraham through his descendants to Muhammad.

To illustrate this, imagine a spoon passed down through generations in a family. Each generation uses it daily, teaching their children how to use it properly; not by reading instructions, but by example and practice. The spoon’s use is understood and preserved through living tradition, not written manuals. Similarly, the community’s established practice carries the authentic knowledge of worship without needing explicit hadith instruction for every detail.