There is a widespread misconception among Muslims that women cannot pray during menstruation, but this belief has no basis in the Quran. Nowhere in the Quran does God prohibit women from performing the contact prayer (ṣalāh) while on their period. The idea that menstruation should prevent a woman from engaging in prayer must therefore be from Satan, as he is the one who seeks to prevent believers from maintaining their connection with God. If a woman refrains from praying during menstruation, this results in a significant loss of worship.

Calculation of Lost Prayers

Calculate the total number of days of prayer from age 12 to 80:

- Total years from age 12 to 80: (80 – 12 = 68) years.

- Total days of prayer: 68 x 365 = 24,820 days.

Calculate the total number of prayers from age 12 to 80

- Total prayers: (24,820 x 5 = 124,100) prayers.

Calculate the number of prayers missed due to menstruation from age 12 to 55:

- According to the study, the median number of lifetime menstrual cycles is 451.3, corresponding to 34.7 years of menstrual activity.

- The woman in the example menstruates from age 12 to 55, which is 43 years. If we assume an average of 13 cycles per year, she would have approximately 43×13=559 menstrual cycles.

- Assuming an average menstruation lasts about 5 days, the total days of menstruation would be 559×5=2,795 days.

- Total missed prayers: 2,795×5=13,975 prayers.

Calculate the percentage of missed prayers from age 12 to 80:

Percentage of missed prayers: (13,975/124,100) x 100.

The woman missed about 13,975 prayers due to menstruation from age 12 to 55. Over her entire lifetime of required prayer from age 12 to 80, this accounts for approximately 11.26% of the prayers she was supposed to perform.

Such a substantial disruption in worship cannot be justified, especially when the Quran emphasizes the importance of consistent prayer under all circumstances. In fact, the Quran makes provisions for individuals to pray even when they are ill, traveling, or in situations where physical movements are not possible—allowing prayer while walking, sitting, or even mentally if necessary. If these allowances exist, then there is no justification for excluding menstruating women from prayer. To prohibit them from praying is a man-made innovation that directly contradicts the Quranic principle of maintaining regular prayer. The contact prayer is an act of worship that must never be abandoned, and menstruation is no exception. Therefore, women must continue praying regardless of their menstrual state, as there is no valid excuse to discontinue an obligation so central to Islamic practice. This raises a profound question: How was the entirety of the Muslim ummah deceived into accepting a practice that results in women abandoning approximately 11.26% of their obligatory prayers across their lifetime?

Consider the cumulative impact: from 740 CE to 2025 CE—a period of 1,285 years—the practice has affected innumerable Muslim women across generations. Using historical estimates, the Muslim population began at several million in the 8th century and grew to nearly 2 billion today, with approximately half being women. Even with conservative estimates accounting for population growth patterns over these centuries, hundreds of millions of women would have missed billions of prayers collectively. If each woman missed approximately 13,975 prayers in her lifetime due to this practice, the spiritual impact across Islamic history represents an enormous deviation from what may have been divine intention for consistent worship.

Our Earliest Source(s)

According to the book “Hadith Muhammad’s Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World,” by Jonathan Brown, it states:

The version of the Muwatta that became famous in North Africa and Andalusia contains 1,720 reports. Of these, however, only 527 are Prophetic hadiths; 613 are statements of the Companions, 285 are from Successors, and the rest are Malik’s own opinions.

To understand the historical Islamic position on prayer during menstruation, we must examine the earliest and most authoritative jurisprudential sources. The Muwatta of Imam Malik (711-795 CE/93-179 AH) stands as the earliest written collection of hadith specifically addressing legal matters, compiled in Medina – the first Muslim state established by the Prophet Muhammad himself. This uniquely positions the Muwatta to reflect the authentic practices of the earliest Muslim community. Unlike later compilations, the Muwatta blends prophetic traditions (822 attributed directly to Muhammad) with companion sayings and Imam Malik’s own juridical interpretations (898 additional reports), creating a comprehensive legal framework.

The text’s authenticity is particularly noteworthy, with PERF No. 731 dating to approximately 793 CE/176 AH during Malik’s lifetime. The Muwatta represents our most direct window into early Islamic jurisprudential practice. If we truly seek to understand how the first generations of Muslims approached the question of prayer during menstruation, the Muwatta offers the most authoritative guidance, reflecting the practices of those closest to prophetic teaching in both time and place.

The Narrations Concerning Prayer and Menstruation in The Muwatta

Hisham’s Narration

Yahya related to me from Malik from Hisham ibn Urwa from his father that A’isha, the wife of the Prophet, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, said,

“Fatima bint Abu Hubaysh said, ‘Messenger of Allah, I never become pure – am I permitted to pray?‘ The Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, said, ‘That is a vein, not menstruation. So when your period approaches, leave off from the prayer, and when its grip leaves, wash the blood from yourself and pray.’ “

(Muwatta, Book 2, Hadith 106)

Nafi’s Narration

Yahya related to me from Malik from Nafi from Sulayman ibn Yasar from Umm Salama, the wife of the Prophet, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, that

a certain woman in the time of the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, used to bleed profusely, so Umm Salama consulted the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, for her, and he said, “She should calculate the number of nights and days a month that she used to menstruate before it started happening, and she should leave off from prayerfor that much of the month. When she has completed that she should do ghusl, bind her private parts with a cloth, and then pray.”

(Muwatta, Book 2, Hadith 107)

Disconnected Chain (Malik < unknown < Aish)

Yahya related to me from Malik that he had heard that A’isha, the wife of the Prophet, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, said

that a pregnant woman who noticed bleeding left off from prayer.

(Muwatta, Book 2, Hadith 102)

Malik Openly Stating Medina’s Position Founded on Hisham’s Hadith

Yahya related to me from Malik from Hisham ibn Urwa that his father said, “A woman who bleeds as if menstruating only has to do one ghusl, and then after that she does wudu for each prayer.”

Yahya said that Malik said, “The position with us is that when a woman who bleeds as if menstruating starts to do the prayer again, her husband can have sexual intercourse with her. Similarly, if a woman who has given birth sees blood after she has reached the fullest extent that bleeding normally restrains women, her husband can have sexual intercourse with her and she is in the same position as a woman who bleeds as if menstruating.”

Yahya said that Malik said, “The position with us concerning a woman who bleeds as if menstruating is founded on the hadith of Hisham ibn Urwa from his father, and it is what I prefer the most of what I have heard about the matter.“

Hisham’s Narration 1 – (the precursor to it all)

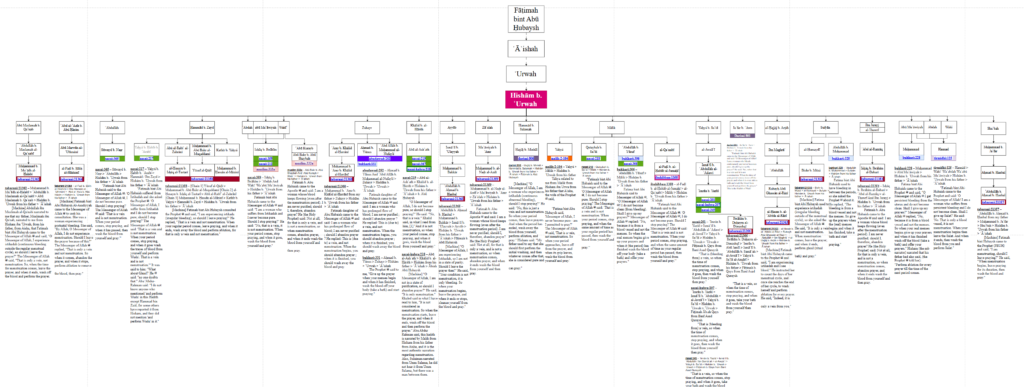

Hishām ibn ʿUrwah (61–146 A.H./680–763 CE) was a prominent hadith narrator from Medina. The son of ʿUrwah ibn al-Zubayr and a concubine, he was the grandson of Zubayr ibn al-ʿAwwām and Asmāʾ bint Abī Bakr (sister of Aisha, the wife of the prophet). He married Fāṭima bint Mundhir, with whom he had three sons: al-Zubayr, ʿUrwah, and Muḥammad. Renowned for his transmission of hadith, he later moved to Iraq, where he passed away in Baghdad at the age of 83.

He narrates this hadith to Imam Malik:

“”Fatima bint Abu Hubaysh said, ‘Messenger of Allah, I never become pure – am I permitted to pray?‘ The Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, said, ‘That is a vein, not menstruation. So when your period approaches, leave off from the prayer, and when its grip leaves, wash the blood from yourself and pray.’ “”(Muwatta, Book 2, Hadith 106)

This narration addresses a specific medical condition known as istihadha (irregular vaginal bleeding outside of normal menstruation). In it, Fatima bint Abu Hubaysh approaches the Prophet Muhammad with a concern that she “never becomes pure,” meaning she experiences continuous bleeding that prevents her from achieving ritual purity. She asks if she can pray despite this ongoing condition. The Prophet clarifies that her continuous bleeding is from “a vein” (a physical ailment) and not true menstruation. He instructs her to distinguish between her actual menstrual period and this other bleeding. During her actual menstrual period, she should refrain from prayer as normal. However, when her regular menstrual bleeding ends, even if the abnormal bleeding continues, she should wash herself and resume praying. This narration establishes an important distinction between menstruation (which affects ritual obligations) and other forms of vaginal bleeding (which do not prevent prayer after proper cleansing). When we coalesce these 36+ narrations found in a large variety of hadith compilations, we find that the massive proliferator of the hadith is no other than Hisham ibn Urwa (diagram is too big to fit it all on the page):

Imam Malik states in Book 2, Hadith 110 of his Muwatta, that “…the position with us concerning a woman who bleeds as if menstruating is founded on the hadith of Hisham ibn Urwa from his father, and it is what I prefer the most of what I have heard about the matter.” This statement is particularly significant coming from Imam Malik, who was renowned as the Imam of the Prophet’s city (Medina) and whose legal opinions reflected the continuous practice of the Medinan community. The fact that he specifically cites Hisham ibn Urwa’s hadith as the basis for preventing women from praying during menstruation demonstrates that this practice was established early in Islamic jurisprudence and considered authoritative by Imam Malik, and by virtue, Medinan authorities.

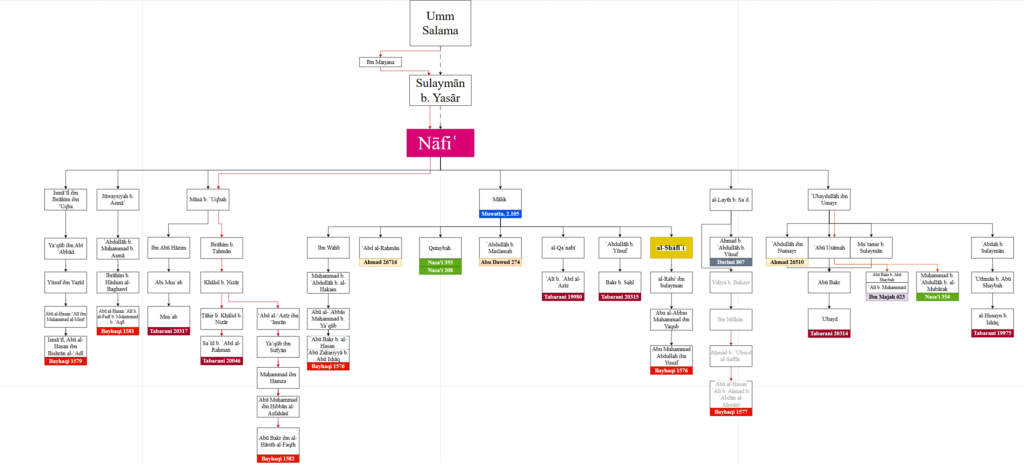

Nafi’s Narration

Nafi’ was a prominent early Islamic scholar and hadith transmitter who lived during the late Umayyad and early Abbasid periods, dying around 117-120 AH (735-738 CE). Originally a Berber from North Africa, he was brought to Medina as a slave and became the mawla (freed client) of Abdullah ibn Umar, one of the most respected companions of the Prophet Muhammad. His students included some of the most important scholars of his time, most notably Imam Malik ibn Anas, the founder of the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence. Malik considered Nafi’ an extremely important source of knowledge and frequently transmitted traditions through him.

In the complex world of early hadith transmission, Nafi’ became a subject of scholarly investigation. Modern scholars like Juynboll have critically examined his role in hadith transmission, noting both his traditional importance and the nuanced reality of his scholarly contributions.

He narrates this hadith to Imam Malik:

“a certain woman in the time of the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, used to bleed profusely, so Umm Salama consulted the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, for her, and he said, “She should calculate the number of nights and days a month that she used to menstruate before it started happening, and she should leave off from prayerfor that much of the month. When she has completed that she should do ghusl, bind her private parts with a cloth, and then pray.” (Muwatta, Book 2, Hadith 107)

Imam Malik was likely not acting maliciously, but sincerely believed he was following prophetic guidance. The narrative suggests that Hisham ibn Urwa initiated the prohibition against women praying during menstruation through his fabricated hadith. Malik, known for his scholarly integrity, would have accepted this narration in good faith, believing it to be an authentic transmission from the Prophet.

Nafi’, as a key transmitter, then provided the additional legal elaborations and nuanced rulings that naturally emerge from such a prohibition. These detailed narrations would have given the ruling more depth and credibility, addressing practical questions about implementation. Malik, committed to preserving what he believed to be authentic prophetic tradition, would have accepted these narrations as legitimate extensions of the original ruling. The scholarly mechanism of the isnad (chain of transmission) was intended to ensure authenticity, but was instead used as a method for introducing rulings that may not have originated with the Prophet himself. Malik’s acceptance would have been based on his trust in the integrity of the transmitters and his commitment to what he understood as divine guidance.

There’s another narration that’s worth looking into – Bayhaqi 1576

Al-Bayhaqī (1576) – Abū Zakariyyā ibn Abī Isḥāq and Abū Bakr ibn al-Ḥasan both narrated to us, saying: Abū al-‘Abbās Muḥammad ibn Ya‘qūb narrated to us, saying: Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-Ḥakam informed us, saying: Ibn Wahb narrated from Mālik.

Additionally, Abū Muḥammad ‘Abd Allāh ibn Yūsuf dictated to us, saying: Abū al-‘Abbās Muḥammad ibn Ya‘qūb narrated to us, saying: al-Rabī‘ ibn Sulaymān informed us, saying: al-Shāfi‘ī narrated to us, saying: Mālik narrated from Nāfi‘, the freed slave of Ibn ‘Umar, from Sulaymān ibn Yasār, from Umm Salama, the wife of the Prophet ﷺ, who said:

“A woman used to have continuous bleeding during the time of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ, so Umm Salama sought a ruling for her from the Messenger of Allah ﷺ. He said: ‘She should determine the number of nights and days she used to menstruate each month before this condition affected her, and she should refrain from prayer for that period. After that time has passed, she should perform ghusl, wrap herself with a cloth, and then pray.’”

The wording of al-Shāfi‘ī’s narration is: “This is a well-known ḥadīth, which Mālik ibn Anas included in his Muwaṭṭaʾ and which Abū Dāwūd recorded in his Sunan. However, Sulaymān ibn Yasār did not hear it directly from Umm Salama.“

Not only do we have evidence from Mālik that his narration was built upon Hishām’s narration, but we also have clear proof from al-Shāfi‘ī that Mālik definitively used this “well-known” hadith as a legal ruling. The fact that al-Shāfi‘ī transmits this narration demonstrates how this ruling rapidly spread across Muslim lands, giving rise to new traditions and variant hadiths—all of which ultimately trace back to Hishām’s prohibitive hadith. This propagation underscores how a single narration could evolve into multiple differing reports, shaping Islamic legal discourse in the process.

Hishām’s hadith served as the foundation upon which later narrators, particularly al-Zuhrī, constructed their own versions to establish authority and proof for the ruling on istiḥāḍa (non-menstrual bleeding). The core elements of Hishām’s narration—where the Prophet ﷺ distinguishes between menstruation and a vein, instructing the woman to refrain from prayer during her period and wash before resuming—are preserved in al-Zuhrī’s version. However, al-Zuhrī introduces significant modifications. Unlike Hishām’s direct report from Fāṭima bint Abī Hubaysh, al-Zuhrī attributes his narration to ʿĀʾisha via ʿAmrah bint ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, thereby shifting the authority to a more prominent figure while omitting Hishām entirely:

Al-Zuhri’s Copying of Hisham’s Hadith of Medina

Zuhri’s:

ahmad:24538 – Abū al-Mughīrah > al-Awzāʿī > al-Zuhrī > ʿUrwah > ʿAmrah b. ʿAbd al-Raḥman b. Saʿd b. Zurārah

‘Aishah the wife of the Prophet said: “Umm Habibah Jahsh experienced prolonged non-menstrual bleeding for seven years when she was married to ‘Abdur-Rahman bin ‘Awf. She complained about that to the Prophet and the Prophet said: ‘That is not menstruation, rather it is a vein, so when the time of your period comes, leave the prayer, and when it is over, take a bath and perform prayer.'” ‘Aishah said: “She used to bathe for every prayer and then perform the prayer. She used to sit in a washtub belonging to her sister Zainab bint Jahsh and the blood would turn the water red.”

Hisham’s/Medinans:

darimi:806 – Ḥajjāj b. Minhāl > Ḥammād b. Salamah > Hishām b. ʿUrwah from his father > ʿĀʾishah > Fāṭimah b. Abū Ḥubaysh

“O Messenger of Allah, I [Fatima b. Abu Hubaysh] am a woman who experiences istihadah (continuous abnormal bleeding), should I stop praying?” He said: “No, this is just a vein and not menstruation. So when your period comes, then leave prayers. And when the period has ended, wash away the blood from yourself, perform ablution, and pray.” Hisham said: “My father used to say that she should first perform the initial washing, and then whatever comes after that, she is considered pure and can pray.”

Furthermore, al-Zuhrī’s version expands the narrative by introducing a different protagonist—Umm Ḥabība bint Jaḥsh—who suffers from istiḥāḍa for seven years, emphasizing her prolonged struggle. The ruling also becomes stricter, as Umm Ḥabība is instructed to perform ablution for every prayer despite continuous bleeding, a detail absent in Hishām’s simpler version. This transformation reveals how narrators from different regions adapted Hishām’s foundational hadith, modifying its details to reinforce legal rulings and establish their own authoritative chains of transmission, ultimately creating multiple traditions that all stemmed from the same original source – Hisham’s.

[96:9] Have you seen the one who enjoins.

[96:10] Others from praying?

Rough Estimate of How Many Prayer’s Have Been/Will Be Lost In The Current Era

keep in mind liberties were taken with population

Step 1: Calculate the Total Number of Muslim Women

Research statistics tell us there are roughly 800 million Muslim women worldwide

Step 2: Calculate the Average Number of Prayers Missed Per Woman

From previous calculations, the average number of prayers missed by a woman due to menstruation over her lifetime is approximately 13,975 prayers.

Step 3: Calculate the Total Number of Prayers Missed

Total Missed Prayers = 800,000,000 x 13,975 = 1.118 x 10^13 prayers

The total number of prayers missed due to menstruation by 800 million Muslim women is approximately 1.118 x 10^13 (11,180,000,000,000 or eleven trillion, one hundred eighty billion) prayers. This calculation assumes each woman misses, on average, 13,975 prayers over her lifetime.

Some may argue that the hadith of Al-Zuhri allows for women to ‘make up’ the prayers after their menstruation is over. This concept of making up prayers, however, is false. The Quran states all prayers are to be made within their specific periods. Therefore, missing a prayer period would render it missed for good.

[4:103] Once you complete your Contact Prayer (Salat), you shall remember GOD while standing, sitting, or lying down. Once the war is over, you shall observe the Contact Prayers (Salat); the Contact Prayers (Salat) are decreed for the believers at specific times.

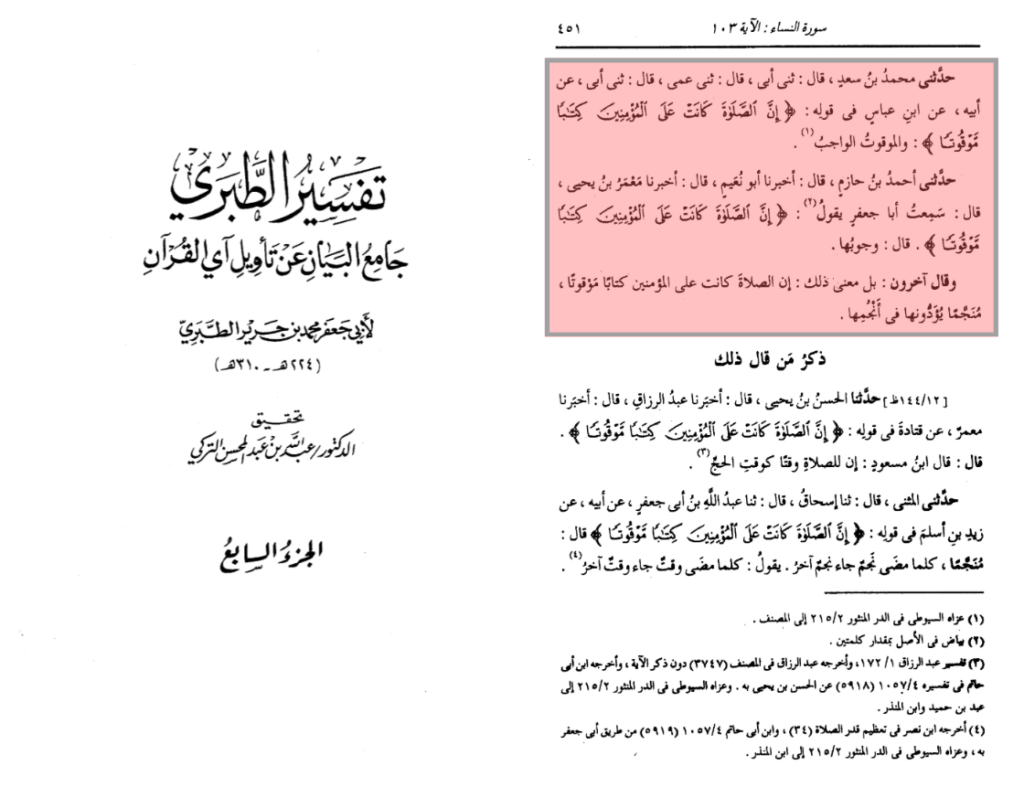

Tabari argues for this same point – prayers can not be made up once the window has passed.

Tabari’s Tafsir of 4:103 –

…the meaning of “Indeed, the prayer has been prescribed upon the believers at fixed times” is that it was ordained in a gradual manner, with believers performing it at its designated times.

Those who held this view include:

- Al-Hasan ibn Yahya, who narrated from Abd al-Razzaq, who narrated from Ma‘mar, from Qatadah, regarding the verse “Indeed, the prayer has been prescribed upon the believers at fixed times”, who said: Ibn Mas‘ud said: “The prayer has a fixed time, just as Hajj has a fixed time.”

- Al-Muthanna, who narrated from Ishaq, who narrated from Ibn Abi Ja‘far, from his father, from Zayd ibn Aslam regarding the verse “Indeed, the prayer has been prescribed upon the believers at fixed times”, who said: “It was ordained in stages; as one time passes, another time follows. Meaning, as one prayer time ends, the next prayer time begins.”

- Al-Qasim, who narrated from Al-Husayn, who narrated from Hajjaj, from Abu Ja‘far al-Razi, from Zayd ibn Aslam with the same explanation.

Abu Ja‘far (the commentator) said: These explanations are all closely related in meaning, for what is obligatory is required, and what is required to be performed at specific times is “gradual” (i.e., scheduled at intervals).

However, the most appropriate interpretation of the phrase “prescribed at fixed times” is the view of those who said:

“The prayer was imposed upon believers in a scheduled manner.”

This is because the word “mowqoot” (موقوت) is derived from the verb “waqata” (وَقَتَ), meaning “to assign a fixed time” for something. Thus, when God assigned fixed times for the performance of prayer, it became obligatory within those times.

Accordingly, the meaning of the verse “Indeed, the prayer has been prescribed upon the believers at fixed times” is: “It was imposed upon the believers as an obligation with specific times for its performance, which were made clear to them.”