The process of collecting and canonizing the Quran stands as one of the most pivotal moments in early Islamic history. Traditional accounts often present this as a divinely guided and flawlessly preserved endeavor. However, a closer look at historical sources and primary texts raises questions about the accuracy of this portrayal. Specifically, we’ll explore the inclusion of verses 9:128-129 in Sūrat al-Tawbah (or more accurately, Sūrat al-Bara’a), suggesting that evidence from hadith literature points to these verses possibly being later additions to the Quranic text.

*This analysis serves as an internal critique using Sunni sources to demonstrate that their own historical records cast doubt on the legitimacy of these verses. While this argument is valuable in responding to Sunni critiques, it should be noted that the mathematical structure of Code 19 provides independent verification of these verses’ inauthenticity, offering a criterion for textual authenticity that does not rely on hadith literature at all.

The Anomalous Testimony of Khuzaima ibn Thabit

“…So I started locating Qur’anic material and collecting it from parchments, scapula, leaf-stalks of date palms and from the memories of men (who knew it by heart). I found with Khuza`ima two Verses of Surat-at-Tauba which I had not found with anybody else, (and they were):– “Verily there has come to you an Apostle (Muhammad) from amongst yourselves. It grieves him that you should receive any injury or difficulty He (Muhammad) is ardently anxious over you (to be rightly guided)” (9.128) The manuscript on which the Qur’an was collected, remained with Abu Bakr till Allah took him unto Him, and then with `Umar till Allah took him unto Him, and finally it remained with Hafsa, `Umar’s daughter.”

The cornerstone of this analysis is the widely accepted hadith in Sahih al-Bukhari (4679), which documents Zaid ibn Thabit’s collection of the Qur’an during Abu Bakr’s caliphate. This hadith explicitly states that verses 9:128-129 were found exclusively with Khuzaima ibn Thabit al-Ansari and “not with anybody else.” This singularity constitutes a significant anomaly for several reasons:

- The standard for Qur’anic inclusion established in the same narrative required multiple attestations

- Sūrat al-Tawbah is generally classified as a Medinan surah, while these final verses bear stylistic and thematic similarities to Meccan revelations

- The location of these verses at the precise conclusion of the surah raises questions about their integration into the textual flow

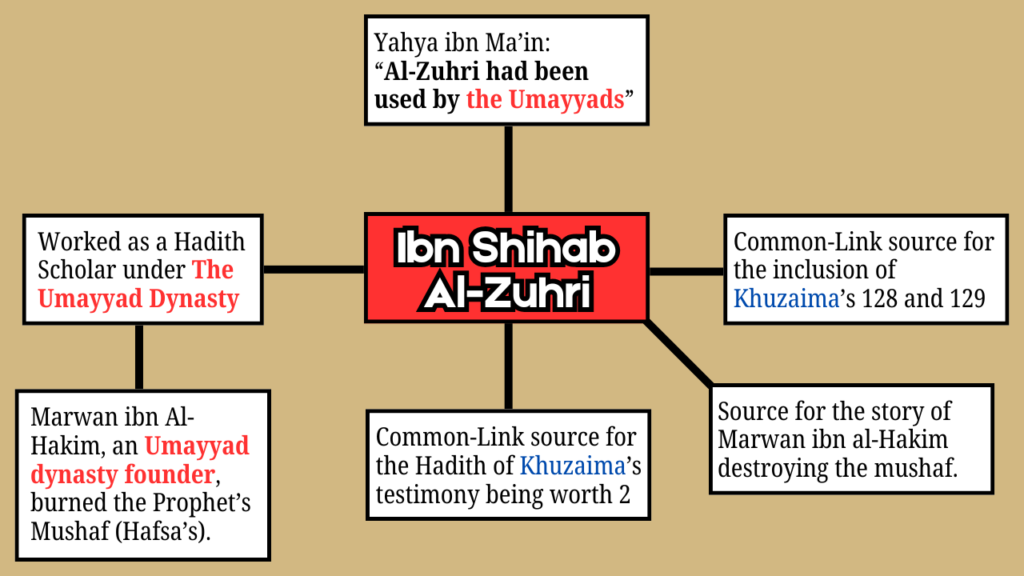

The Al-Zuhri Connection: Common Link Analysis

Critical examination of isnad (transmission chains) reveals that Muhammad ibn Shihab al-Zuhri (d. 742 CE) functions as the common link for both:

- The narrative describing Khuzaima as the sole source for 9:128-129

- The separate tradition elevating Khuzaima’s testimony to equal that of two witnesses

The fact that al-Zuhri is the common link in these accounts is not just a coincidence. He was closely connected to the Umayyad rulers, meaning he had direct access to those in power during a time when religious stories were being shaped to support the political authority of the empire. His role as the main source for both religious traditions raises concerns that these narratives might have been deliberately created, rather than being independent accounts of history. The lack of alternative sources that don’t go through al-Zuhri makes us question whether these stories are truly authentic, especially when we consider traditional methods of analyzing hadith.

When we look at both the chain of transmission (isnad) and the content of the stories (matn), we see that all the parts that back up Khuzaima’s unique testimony trace back to al-Zuhri, who is the earliest known source. This pattern suggests that these stories might have been altered or even created. Given that al-Zuhri lived about a century after the events he’s describing, there was plenty of time for these narratives to be shaped in a way that supported decisions already made during the compilation of the Quran under Uthman.

The Suspicious Secondary Tradition

It was narrated from ‘Umarah bin Khuzaimah that his paternal uncle, who was one of the companions of the Prophet told him, that:

Narrated Uncle of Umarah ibn Khuzaymah:

The Prophet (ﷺ) bought a horse from a Bedouin. The Prophet (ﷺ) took him with him to pay him the price of his horse. The Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) walked quickly and the Bedouin walked slowly. The people stopped the Bedouin and began to bargain with him for the horse as and they did not know that the Prophet (ﷺ) had bought it.

The Bedouin called the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) saying: If you want this horse, (then buy it), otherwise I shall sell it. The Prophet (ﷺ) stopped when he heard the call of the Bedouin, and said: Have I not bought it from you? The Bedouin said: I swear by Allah, I have not sold it to you. The Prophet (ﷺ) said: Yes, I have bought it from you. The Bedouin began to say: Bring a witness. Khuzaymah ibn Thabit then said: I bear witness that you have bought it. The Prophet (ﷺ) turned to Khuzaymah and said: On what (grounds) do you bear witness? He said: By considering you trustworthy, Messenger of Allah (ﷺ)! The Prophet (ﷺ) made the witness of Khuzaymah equivalent to the witness of two people.

The tradition that says Khuzaima’s testimony is worth as much as two men seems to have been created to explain the problem in the first hadith. There are a few reasons to think this is the case. First, this story only appears in later hadith collections (like Sunan al-Nasa’i and Abu Dawud), not in earlier ones, suggesting it was added later in response to questions about why a single person’s testimony was being accepted. Second, it conveniently explains why a single person’s word was accepted when the normal rule required two witnesses. Third, the logic of the story is questionable: Khuzaima claims to testify about something he didn’t actually see, yet instead of being corrected, he’s praised.

This story doesn’t align well with what the Quran says about valid testimony. The Quran clearly outlines that valid testimony requires direct observation of an event (for example, in 4:15). However, in the case of Khuzaima, he admits he didn’t witness the event between the Prophet and the Bedouin, and instead, he testifies based on his belief in the Prophet’s honesty. Rather than being corrected for this misapplication of testimony, he’s oddly rewarded by having his word counted as equivalent to two witnesses, even though technically, he didn’t give an accurate witness.

What’s even more puzzling is that this exception for Khuzaima contradicts clear Quranic rules. In 2:282, the Quran gives specific instructions for providing testimony in contracts, emphasizing the need for multiple reliable witnesses. If such care is needed for something as worldly as contracts, surely the preservation of divine revelation should have even stricter rules. But in this case, the rule seems to be ignored. Instead of requiring multiple confirmations, the testimony of a single person—who didn’t even witness the event directly—is accepted as enough.

The Fate of the Original Manuscripts

The report from Kitab al-Masahif that Marwan ibn al-Hakam destroyed the original mushaf “fearing the eruption of new disputes” provides critical context. This deliberate elimination of primary evidence that could have resolved textual questions suggests possible knowledge of discrepancies between the standardized text and earlier versions.

Ibn Shihab Al-Zuhri narrated that Salim bin Abdullah said: When Hafsa passed away, Abdullah bin Umar sent her scrolls to Marwan. Marwan took them and burned them to avoid any discrepancies, following the example of Uthman’s compilation of the Qur’an.

The Fate of the Original Manuscripts

The narrative concerning this destruction also traces back to Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri, creating a troubling convergence of transmission chains around a single figure with documented Umayyad connections. According to early rijal experts, al-Zuhri’s reputation among hadith scholars was “a chequered one.” Yahya ibn Ma’in—one of the most respected early critics of hadith transmitters—explicitly stated his preference for A’mash over al-Zuhri because “he [al-Zuhri] did not let himself be used by the authorities as Zuhri had been used by the Umayyads.” This assessment from a contemporary expert raises serious questions about al-Zuhri’s independence as a transmitter, particularly for narratives that directly served Umayyad interests.

The proximity between al-Zuhri and Marwan ibn al-Hakam’s administration is a troubling connection between the figure responsible for transmitting the justification for including verses 9:128-129 and the political authority that eliminated the primary manuscript evidence. This relationship suggests not merely coincidental transmission but potentially coordinated narrative construction that served to legitimize the Uthmanic recension while simultaneously removing material evidence that might contradict it. The destruction of Hafsa’s manuscript—which represented the Prophet’s own mushaf—effectively eliminated any possibility of textual comparison that might have revealed the interpolation of these verses, conveniently reinforcing the narrative al-Zuhri himself was instrumental in propagating.

Conclusion

The evidence points to a more intentional shaping of history than has been previously acknowledged. During the official compilation of the Quran under Uthman, verses 9:128-129 seem to have been added based solely on Khuzaima’s testimony, which was passed down only through al-Zuhri. This same al-Zuhri, who was deeply involved with the Umayyad administration, played a key role in creating the historical narrative that supported this inclusion. Later, a tradition was introduced to elevate the value of Khuzaima’s testimony. This becomes even more concerning when we take into account the criticism of Yahya ibn Ma’in, one of the most respected hadith critics, who openly accused al-Zuhri of being manipulated by the Umayyads.

This network of interconnected narratives forms a coherent pattern: al-Zuhri transmits the account of Khuzaima’s singular possession of verses 9:128-129, provides the justification for accepting this single testimony through the second hadith, and is connected to the political apparatus under which Marwan ibn al-Hakam destroyed the original manuscripts that could have verified or refuted these claims. The destruction of earlier manuscripts by Marwan eliminated potential contradictory evidence, effectively securing the canonical status of these verses while removing the means to challenge their authenticity.

This analysis serves as an internal critique, using Sunni sources to highlight serious doubts about the authenticity of these verses. The fact that all relevant transmissions link back to one figure with clear political ties, combined with the destruction of crucial evidence under his administration, makes a strong case for questioning the legitimacy of 9:128-129. While this argument relies on traditional Islamic source criticism to address Sunni objections, it is also supported by the mathematical structure of Code 19, which independently challenges the authenticity of these verses, offering an alternative criterion for textual verification that doesn’t depend on hadith literature.

A lot of people when they are able to weaken a hadith, throw the baby out with the bathwater. They just throw everything in the trash as if “there’s nothing to see here”. But a more nuanced approach is warranted. WHY THE HELL DID AL-ZUHRI FABRICATE HADITH ATTEMPTING TO JUSTIFY 9:128-129 IN THE FIRST PLACE?

You don’t fabricate justifications for things that are already universally accepted. You fabricate when something needs to be justified—when there’s tension, resistance, or inconsistency that needs to be patched up. It appears he was responding to a real and persistent unease in the early Muslim community about these verses. The very fact that such a hadith exists suggests that there was real, lingering discomfort within the early Muslim community about these verses. Al-Zuhri’s narrative didn’t arise in a vacuum—it appears to be a strategic, retroactive attempt to legitimize verses whose inclusion was already being questioned. That raises a bigger issue: Why were those verses being questioned in the first place? What exactly happened during the compilation of the Qur’an that led to these lingering doubts in the early Muslim community that they had to address?

Al-Zuhri—a man whose fingerprints are all over this mess, and who just happens to be deeply entangled with Umayyad power. He helped craft an “official” narrative that conveniently aligned with political interests: quelling the doubts and anxieties that have been lingering regarding these verses.

This isn’t a weak hadith problem. If you accept these hadiths, you have a problem, if you reject these hadiths, you have an even bigger problem.