The science of Qiraat (variant readings of the Qur’an) stands as a discipline of significance, yet one that has received comparatively little critical examination through the methodological frameworks applied to other textual traditions (like the hadith). While the transmitters of hadith literature have been evaluated through Ilm al-Rijal (the science of narrator criticism), the transmitters of Qiraat have largely escaped similar levels of scrutiny in their acceptance of the Quran in the later period.

The canonization of the “Seven Readings” by Ibn Mujahid in the 4th century AH established a framework for Qur’anic recitation that persists to the present day. However, a concerning pattern emerges when we apply the meticulous standards of narrator reliability developed in hadith scholarship to these transmitters of Qur’anic variants. I will attempt to collect biographical data, contemporaneous assessments, and chain analysis to evaluate whether the transmitters who shaped our understanding of Qur’anic recitation would meet the stringent criteria applied to those who transmitted prophetic traditions.

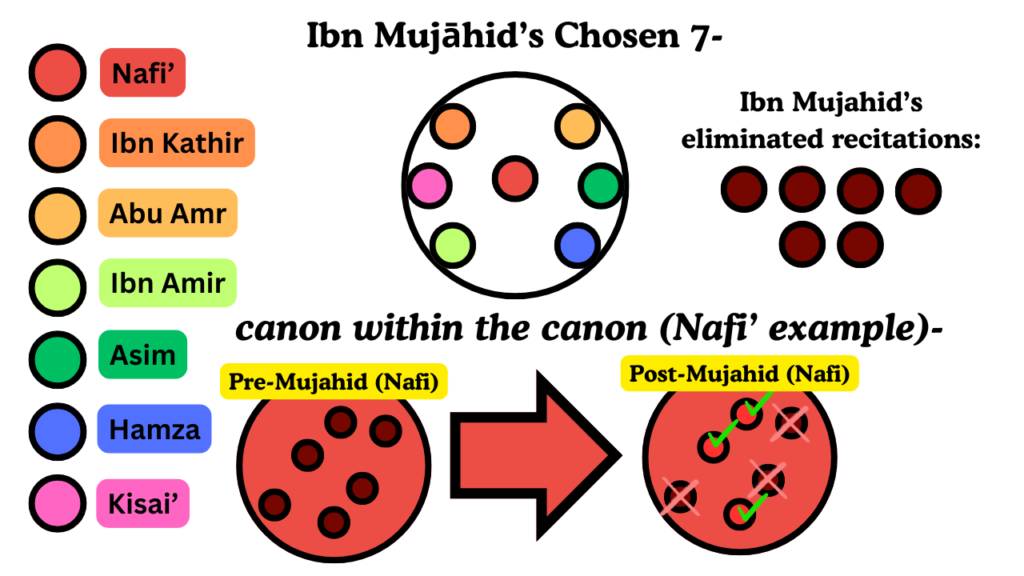

Ibn Mujahid – ‘These are the 7 – that’s it.’

In the 4th century AH, Ibn Mujāhid undertook a monumental task: not only did he select seven authoritative reading systems from many existing options, but he also attempted to standardize each one internally. This was essentially a double canonization process – first selecting which reading systems would be authoritative, then determining which specific variants within each system should be considered correct.

This standardization was necessary because even within a single reading system, disagreements were common. Different transmitters of the same reading often had conflicting versions of specific words or phrases. To address this problem, Qur’anic scholars adopted methods similar to those used by hadith scholars. They traveled extensively across the Islamic world to verify transmissions, sometimes journeying great distances just to authenticate a single variant reading or to compare versions from different transmitters. Simply put, the more Quran transmissions that these Qiraat transmitters received, the more variants they acquired.

Later Muslim scholarship developed the doctrine that the Seven Readings were completely authentic and “beyond doubt” in their entirety. Similarly, attributing errors to the Companions of the Prophet became unthinkable, as they were all considered absolutely trustworthy (ʿudūl). The tradition though acknowledged that the Quran reciters could have had transmission errors due to basic human error (forgetfulness, poor memorization, senility, etc).

Evidence of Reciter Fallibility

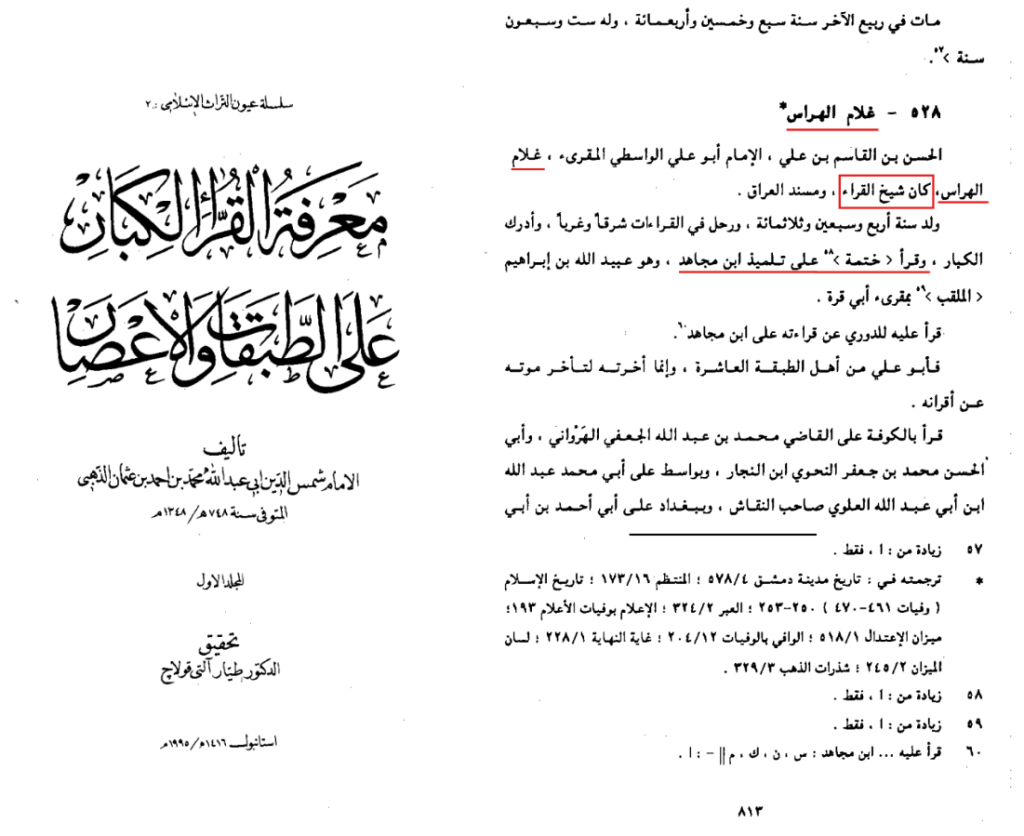

Ghulām al-Harrās <- ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ibrāhīm <- Ibn Mujahid

Abū ʿAlī al-Wāsiṭī, commonly known as Ghulām al-Harrās (d. 468/1075), was a distinguished Qurʾānic reciter of Iraq. He was renowned for having completed a full audition of the Qurʾān under a student of Ibn Mujāhid.

Translation of relevant portion:

528 – Ghulām al-Harrās*

Al-Hasan ibn al-Qasim ibn Ali, Imam Abu Ali al-Wasiti al-Muqriʾ, known as Ghulām al-Harrās, was the senior shaykh of reciters and the hadith transmitter of Iraq.

He was born in the year 174 AH, traveled extensively in pursuit of qirāʾāt (recitations), both eastward and westward, and studied under major scholars. He completed a khatmah (full recitation) under the student of Ibn Mujāhid, namely ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ibrāhīm

…

His biography appears in: “Tārīkh Madīnat Dimashq” (4/578), “Al-Muntaẓim” (16/173), “Tārīkh al-Islām” (250/470-471), “Al-ʿIbar” (2/343), “Al-Iʿlām bi-Wafayāt al-Aʿlām” (193), “Mīzān al-Iʿtidāl” (1/518), “Al-Wāfī bil-Wafayāt” (12/404), “Ghāyat al-Nihāyah” (1/228), “Lisān al-Mīzān” (2/454), and “Mashīkhat al-Dhahabī” (3/339).

Translation of relevant portion:

He used to isolate the letter ʿAyn in recitation, then grew old and lost his sight. Scholars traveled to him in Wāsiṭ from distant lands, and they read to him. His teachings were compiled in the book Al-Kifāyah fī al-Qirāʾāt al-ʿAshr by Abū al-ʿIzz al-Qalānisī, from “three” recitations of Abū al-ʿIzz upon him.

Khamīs al-Muʾaddib said: “He was one-eyed from an early age. I saw him and sat before him many times. He was known as the Imām of the Ḥaramayn, though critics had mixed opinions about him. He narrated ḥadīth from Ibn Khuzafah, and I heard from our companions that he had heard from Abū al-Faḍl ibn Khayrūn.”

Someone said to him: “Abū ʿAlī, the servant of al-Harrās, transmitted from Abū ʿAlī al-Ahwāzī.” He responded: “An embroidered instructor—a liar from a liar.”

Hibat Allāh ibn al-Mubārak al-Saqṭī said: “I was among those who traveled to Abū ʿAlī. I found him to be a knowledgeable and intelligent scholar, skilled, honest, precise, noble, and dignified.”

Abū al-Faḍl ibn Khayrūn said in Al-Riwāyāt: “Ghulām al-Harrās was a reciter, but he made errors in some aspects of Qurʾānic recitation and falsely claimed transmission chains that had no authenticity.”

He reported remarkable things. He passed away on Friday, the 7th of Jumada al-Awwal in the year 468 AH.

I said: “This is more accurate than what Khamees (the Hafidh) said,” who stated that he died at the end of the year 467 AH.

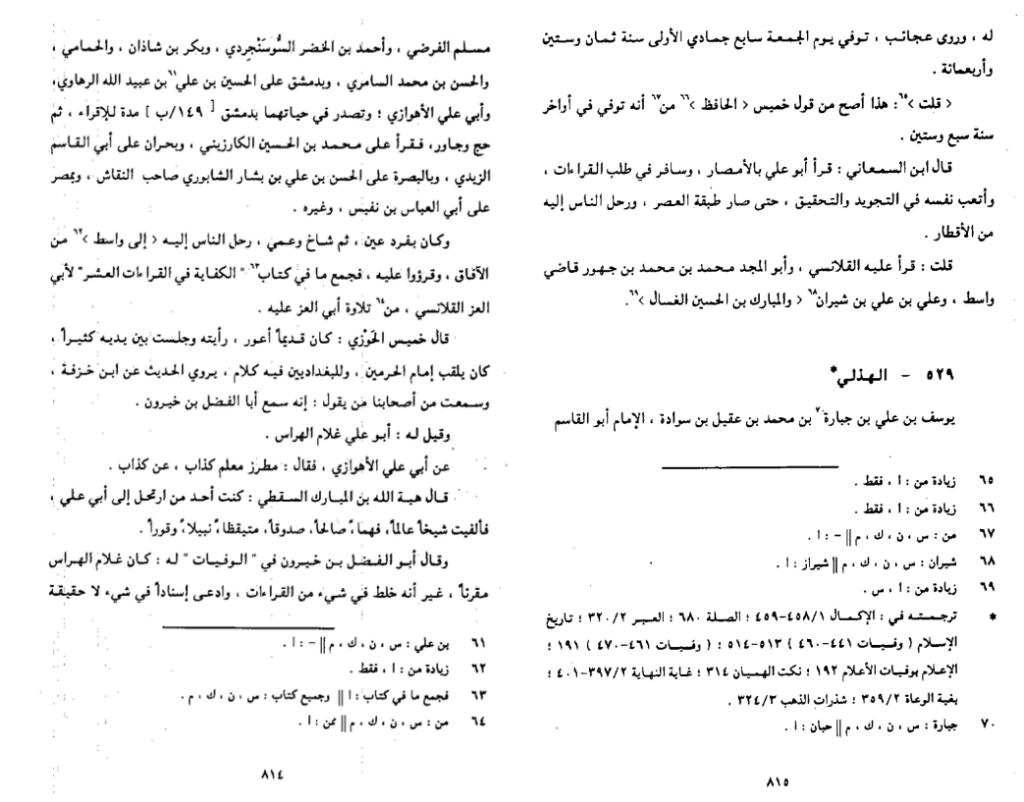

Imam Dhahabi <- Abū Jaʿfar al-Ḥassār

Abū Jaʿfar al-Ḥassār (d. 609/1212) was a distinguished Qurʾān recitation expert from al-Andalus. Both al-Dhahabī and his father studied Qirāʾāt under his guidance.

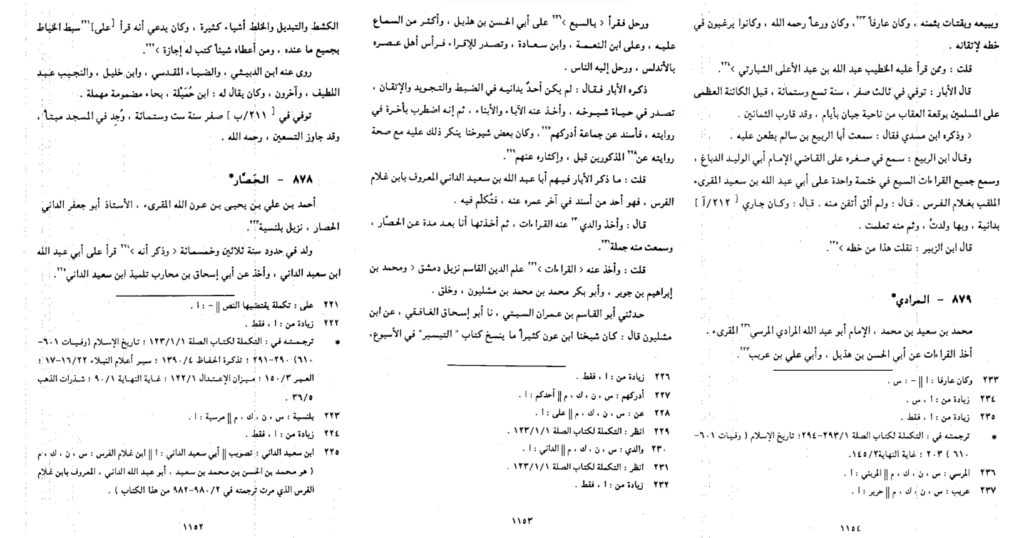

878 – Al-Hassar

Ahmad bin Ali bin Yahya bin ‘Awn Allah Al-Muqri’, the teacher Abu Ja’far Al-Dani Al-Misar, a resident of Valencia.

He was born around the year 530 AH. It was mentioned that he read under Abu Abd Allah Ibn Sa’id Al-Dani and took knowledge from Abu Ishaq bin Muharib, a student of Ibn Sa’id Al-Dani. He traveled and studied [recitation] with Abu al-Hasan ibn Hudhayl, and he listened to him extensively, as well as to Ibn al-Ni‘ma and Ibn Sa‘ada. He became an instructor in recitation and was considered the most knowledgeable of his era in al-Andalus, with people traveling to him.

Al-Abar mentioned him, saying: “No one matched him in precision, strict adherence, and mastery. He took the lead during the lifetime of his teachers, and both fathers and sons studied under him. However, toward the end of his life, his narration became unreliable, and it deteriorated among those who received from him. Some of our teachers rejected this claim, given the authenticity of his earlier narrations and his extensive transmission from them.”

I said: What Al-Abar mentioned includes Abu Abd Allah Ibn Sa‘id al-Dani, known as Ibn Ghulam al-Faras. He was one of the last people to narrate from him, and there was some controversy surrounding him.

Summaries of others:

Abū Aḥmad al-Sāmirī (d. 386/996) was the foremost Qurʾān reciter of his time in Egypt, despite his shortcomings (ʿalā ḍaʿf minhu). He studied under some of the most esteemed Qurʾān scholars, including Ibn Mujāhid, Ibn Shanabūdh (d. 328/939), and al-Ushnānī (d. 307/919). Renowned for his accuracy, reliability, and honesty, al-Sāmirī was widely recognized in scholarly circles. However, he lived to an old age, during which his memorization skills deteriorated (ikhtalla ḥifẓuhu), and he became prone to delusions (laḥiqahu l-wahm). Al-Dhahabī remarked that al-Sāmirī had some of the best isnāds, yet he had to discard them to uphold his scholarly integrity, as multiple scholars accused al-Sāmirī of fabrication and falsehood (qabbaḥa Allāh al-kadhiba wa-dhawīhi).

Jamāl al-Dīn al-ʿAsqalānī (d. 692/1292) was a distinguished Qurʾān reciter of his era. Despite suffering from hemiplegia (fālij), he continued teaching Qurʾānic recitation. Unfortunately, his memory declined over time, leading him to make impermissible pauses (waqf) while reciting the Reading of Ḥamza.

Citation: Dhahabī, Maʿrifat al-qurrāʾ, 2:860–1

Abū l-Ḥusayn al-Lawātī (d. 496/1102) was a prominent scholar and Qurʾān reciter in al-Andalus. He trained under two of the most respected scholars of his time, Makkī l-Qaysī and al-Dānī (d. 444/1052–3). Despite his scholarly contributions, al-Lawātī faced allegations of fabricating isnāds and falsely claiming to have studied with well-known Qurʾān reciters whom he had never actually met.

Citation: Ibn Mujāhid, Sabʿa, 168.

The Dilemma: Fallible People Transmitting Infallible Text

These documented cases reveal an important tension in the Islamic scholarly tradition. On one hand, the Seven Readings themselves and their early sources were elevated to a status of unquestionable authenticity. On the other hand, the actual human chain of transmission that preserved these readings was acknowledged to have weaknesses, particularly in later generations. This historical conundrum challenges these simplistic narratives about textual transmission within early Islam and the Islamic scholarly tradition. It also highlights the sophisticated awareness that these medieval Muslim scholars had about the potential for human error in preserving and transmitting the Quran – even as theological doctrines about textual perfection were simultaneously developing.

Ilm al-Rijal for Qiraat Transmitters

Dr. Nasr asserts, in The Second Canonization of the Qurʾān, that Qirāʾāt scholars did not perform isnād criticism on the chains of transmissions of the Eponymous Readings, nor did they carry out a sophisticated and engaged process of jarḥ and taʿdīl with regards to the rāwīs and readers of the Qurʾān. He argues that a survey of ṭabaqāt dictionaries of both Ḥadīth and Qirāʾāt indicates that the processes of taʿdīl and tazkiya (deeming narrators reliable or not) were not as methodically applied in Qirāʾāt as they were in Ḥadīth. This, he suggests, is evident in the disproportionate number of biographical compilations on muḥaddithūn compared to the scant number on qurrāʾ.

He further notes that besides the two major extant works on the Qurrāʾ by al-Dhahabī and Ibn al-Jazarī, bibliographic sources list a few more titles which are now lost. When we look at pages 107 and 108 of The Second Canonization of the Qurʾān, he is quoted saying,

“Did Qirāʾāt scholars perform isnād criticism on the chains of transmissions of the Eponymous Readings, and did they carry out a sophisticated and engaged process of jarḥ and taʿdīl with regards to the rāwīs and readers of the Qurʾān? The short answer is no. A survey of ṭabaqāt dictionaries of both disciplines, Ḥadīth and Qirāʾāt, gives us a clear indication that the processes of taʿdīl and tazkiya, of deeming readers to be reliable or not, did not take place as methodically in Qirāʾāt as it did in Ḥadīth. This is evident through the sheer number of biographical compilations we have on the muḥaddithūn as compared to the scanty number of books we have on the qurrāʾ. Besides the two major extant works on the Qurrāʾ by al-Dhahabī and Ibn al-Jazarī, bibliographic sources list a few more titles which are now lost.”

Development of Qiraat Isnads

On pages 115 and 116 of The Second Canonization of the Qurʾān, Dr. Nasr argues that the isnād documentation process was not utilized during the generation of the seven Readers (roughly the first quarter of the 2nd/8th century). He points out that Ibn Mujāhid presented chains of transmissions in his introduction to the biographies of the seven Readers, but these were not complete chains of transmission between Ibn Mujāhid and the Prophet. Instead, the Eponymous Readers were, according to written records, asked by their students how they learned their Qirāʾa and with whom they studied. This led to the development of more sophisticated isnāds in later Qirāʾāt manuals, where complete and continuous chains of transmission were introduced, connecting the Qurrāʾ community directly to the Prophet.

He contrasts Ibn Mujāhid’s approach, whose isnād documentation stopped at the Eponymous Readers, with that of Ibn Mihrān, who, in his documentation of the ten Readings, connected each directly to the Prophet through a continuous isnād. However, Dr. Nasr notes that even Ibn Mihrān’s documentation was not without its gaps. For example, while documenting the isnād of the Reading of Ibn Kathīr, Ibn Mihrān stopped at Ubayy b. Kaʿb without directly connecting him to the Prophet, instead adducing a statement by Qunbul on behalf of his teacher al-Qawwās al-Nabbāl: “We are certain that Ubayy received his recitation directly from the Prophet.”

Similarly, regarding the isnād of Ibn ʿĀmir, Ibn Mihrān introduced a statement by Ibn Dhakwān: “Ibn ʿĀmir read the Qurʾān with a certain man, and that man read the Qurʾān with ʿUthmān b. ʿAffān.” To this, Ibn Mihrān added a statement attributed to al-Akhfash al-Dimashqī: “Ibn Dhakwān did not name the man with whom Ibn ʿĀmir studied, but Hishām b. ʿAmmār determined his identity to be al-Mughīra b. Abī Shihāb al-Makhzūmī.”

Tabari’s Kufr of Rejecting Canonical ‘Divine’ Recitations

al- ̇’Tabar ̄ı dismisses Qur’ ̄anic readings attributed to the seven Readers as well, or to be more accurate to those who became known as the seven Readers roughly fifteen years after he died… Al- ̇ Tabar ̄ı states that the genitive reading is not eloquent and that the only reading he authorizes is the accusative wa-l-ar ̇ h ̄ama. Al- ̇ Tabar ̄ı openly dismisses the reading by ̇ Hamzah and considers it to be simply wrong. Again, this grammatically awkward reading by ̇ Hamzah was canonized later on by Ibn Muj ̄ahid and was acknowledged by the community of the Qur” ̄an readers.

In (Q. 6:137) al- ̇ Tabar ̄ı dismisses the reading by the canonical Reader Ibn Amir and considers it to be repulsive and inarticulate. He adds that ̄ this reading cannot be well founded for it contradicts the consensus of the readers. He also rejects Ibn Kath ̄ır’s reading of (Q. 2:37) for the same reasons. Similarly, all these readings openly rejected by al- ̇ Tabar ̄ı were canonized later on and they enjoyed the status of being absolutely valid and divine.

- The Transmission of the Variant Readings of the Quran – Shady Nasser (p. 41-42)

Al-Ṭabarī (d. 310 AH/923 CE), one of the most celebrated exegetes and historians in Islamic tradition, took positions on Quranic recitations that would later create a profound theological tension. His death preceded Ibn Mujāhid’s formal canonization of the seven readings by approximately fifteen years, placing him in a transitional period in the history of Quranic transmission. During this time, al-Ṭabarī explicitly rejected certain recitations that would later be elevated to the status of divine revelation, creating a retrospective theological dilemma of enormous proportions.

Al-Ṭabarī’s commentary contains several instances where he categorically dismisses recitations that were later canonized as divine:

- He rejected the genitive reading of “wa-l-arḥāmi” (Q4:1) by Ḥamzah, considering it “not eloquent” and “simply wrong”

- In Q6:137, al-Ṭabarī dismissed Ibn Amir’s reading as “repulsive and inarticulate,” claiming it “contradicts the consensus of the readers”

- He similarly rejected Ibn Kathīr’s reading of Q2:37

The later canonization of these rejected readings creates a serious theological problem. According to established Islamic doctrine that emerged after al-Ṭabarī, all canonical recitations are considered mutawātir (mass-transmitted), divinely revealed forms of the Quran, equal in validity and authority, and a form of divine revelation that cannot be rejected. If these readings are indeed divine revelation as later Islamic doctrine would maintain, then al-Ṭabarī’s categorical rejection of them constitutes a rejection of divine revelation. In Islamic theology, knowingly rejecting what is established as divine revelation (waḥy) constitutes kufr (disbelief).

- Either the canonized readings that al-Ṭabarī rejected are truly divine revelation, in which case his dismissal of them as “repulsive,” “inarticulate,” and “wrong” constitutes kufr

- Or al-Ṭabarī was correct in rejecting these readings, which would mean that the later process of canonization elevated human linguistic variations to the status of divine revelation

Condemning al-Ṭabarī, one of the most revered authorities in tafsīr, as having committed kufr by rejecting divine revelation would be unthinkable. Yet acknowledging that the canonization process was flawed and that not all canonical readings are truly divine would undermine a central Islamic doctrine.

Al-Ṭabarī’s explicit rejection of readings that would later be canonized exposes a fundamental weakness in the traditional narrative about Quranic transmission. The fact that such a renowned scholar could dismiss as “repulsive” what would later be considered divine revelation reveals the human dimension of the canonization process. This historical reality forces us to recognize that either al-Ṭabarī committed kufr by rejecting divine revelation, or the later process of canonization incorrectly elevated human linguistic variations to the status of divine revelation.

The Regions & Their Recitors

Ibn Mujāhid selected seven eponymous readers to represent valid canonical readings of the Quran, with his choices influenced by regional consensus and adherence to established sunnah1. He selected one reader from each of the major Islamic capitals (al-Madīnah, Makkah, al-Baṣrah, Dimashq) except for al-Kūfah/al-Irāq, from which he chose three.

Mecca- Ibn Kathīr was chosen to represent Mecca because of the consensus among Meccans and its community of qurrā” to recite the Qur’an according to his system. Although other authoritative readers existed, the community of readers of Mecca did not concur with their readings as much as with Ibn Kathīr’s.

Medina- Nāfi’ was selected instead of Abū Ja’far Yazīd because the dominant reading of the people of al-Madīnah was that of Nāfi’.

Damascus- Ibn Mujāhid notes that the majority of the people in Syria followed the reading of Ibn Āmir.

Basra- Abū Amr b. al-Alā” became the chief reader of the city.

Kufa- Al-Kūfah/al-Irāq did not have one single dominant Reading to which the majority of the Kūfan readers adhered. Āṣim was chosen, but his reading was followed by only some Kūfans. Ibn Mujāhid disregarded Kūfan readers who followed the “harf” of Ibn Mas’ūd and chose Āṣim instead. Al-Kisā’ī was a solid authority on Qirā”āt scholarship, and people annotated their Qur’an copies when he recited publicly. Ḥamzah al-Zayyāt was selected, though he was less regarded than other well-respected non-Kūfan readers. The complex situation in Kūfah, with its diverse intellectual and sectarian factions, made it necessary to choose three readers to collectively represent the qurrā” community there.

Biography of The Readers

1) Ibn Amir

He claimed to be from Ḥimyar, but his true genealogy was questionable. There existed nine different statements concerning his isnād up to the Prophet. Some people/someone claimed that it was not known with whom he studied the Qurʾān. (Mizzī, Tahdhīb al-kamāl, 15:145; Shihāb al-Dīn Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī (d. 852/1449), Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb, ed. Ibrāhīm al-Zaybaq and ʿĀdil Murshid, 4 vols. (Beirut: Muʾassasat al-risāla, 1995), 2:363; Ibn al-Jazarī, Ghāya, 1:380.)

1a) Hisham b. Ammar

Hishām b. ʿAmmār: When he got older he became senile (taghayyara) and started to read/recite anything that was given to him. He would repeat and transmit anything people told him [without inquiring about its truth], but he was more trustworthy when he was younger. Hishām transmitted 400 baseless ḥadīths (laysa lahā aṣl) all with [apparently] good isnāds. A man by the name of Faḍlak [Faḍlak al-Rāzī] used to give these ḥadīths to Hishām, who did not hesitate to transmit them; [in doing so] he almost created a rupture in Islām. Hishām was dictating ḥadīth one day when he was asked: “Who gave you this ḥadīth? He answered: ‘One of my teachers (baʿḍ mashāyikhinā)’”. When he was asked again, he yawned/closed his eyes from sleepiness (fa-naʿasa). Muḥammad b. Muslim al-Rāzī said: “I decided to stop narrating the ḥadīths of Hishām because he used to sell ḥadīth/get paid for teaching ḥadīth”. Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal said: “Hishām was fickle and frivolous”. One day, he was sitting in public while his private parts were visible. A man told him: “Cover yourself”! Hishām responded: “Have you seen it [i.e., my penis]? God willing your eyes will never suffer from ramad (ophthalmia)”. Ibn Ḥanbal purportedly said: “One must repeat the prayer if it was led by Hishām”. (Mizzī, Tahdhīb al-kamāl, 30:242–55; Ibn Ḥajar, Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb, 4:276–7.)

1b) Abdallah b. Dhakwan

ʿAbd Allāh b. Dhakwān: There were no derogatory comments recorded about him, except that his father was the brother of Abū Luʾluʾa, the assassin of ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb. (Ibn Ḥajar, Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb, 2:329.)

2) Ibn Kathir

Confusion was recorded in his isnād as to whether he studied the Qurʾān with ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Sāʾib al-Makhzūmī or Mujāhid [b. Jabr].

2a) Bazzi

al-Bazzī: Abū Ḥātim said that al-Bazzī’s ḥadīth was weak and that he would never accept it. Al-ʿUqaylī stated that his ḥadīth was munkar. (Lisān al-Mīzān, ed. ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ Abū Ghudda and Salmān ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ Abū Ghudda, 10 vols. (Beirut: Dār al-bashāʾir al-islāmiyya, 2002), 1:631–3)

2b) Qunbul

Qunbul: He became chief of the Police (shurṭa) in Makka but grew corrupt (kharubat sīratuhu). He lived long and became senile. He stopped teaching the Qurʾān seven years before his death. Ibn al-Munādī narrated that he performed pilgrimage together with Ibn Mujāhid and Ibn Shanabūdh. When they met Qunbul in Makka he was mentally unstable. Ibn Mujāhid started a Qurʾān audition with him, but Qunbul was making so many mistakes in his recitation that Ibn Mujāhid was forced to leave the session. (Ibid., 7:284–5.)

3) Asim

Ibn Saʿd said that he made many mistakes in his ḥadīth. He was not good at memorization, to the extent that Ibn ʿUlayya said: “Anyone whose name was ʿĀṣim had bad memory”. According to Ibn Khirāsh, ʿĀṣim transmitted munkar traditions in his ḥadīth, whereas al-ʿUqaylī said: “There was nothing wrong with him except his bad memory”. Al-Dāraquṭnī stated that something was wrong with ʿĀṣim’s memory, and Ḥammad b. Salama said that he became senile before he died. (Ibn Ḥajar, Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb, 2:250–1.)

(for those munkar traditions, see The Hasanid Mahdi)

3a) Hafs

Ḥafṣ: Ḥafṣ: Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal said that his ḥadīth was not to be transmitted. Ibn Maʿīn stated he was not trustworthy, while al-Madīnī said that his ḥadīth was weak and should be abandoned. Al-Bukhārī said that the Ḥadīth transmitters abandoned Ḥafṣ’s ḥadīth (tarakūhu), and al-Nasāʾī confirmed that his ḥadīth must neither be learned nor written down. Other critics said that all his ḥadīths were manākīr and bawāṭīl (false, invalid). Not only was he untrustworthy in ḥadīth, but it was reported that Shuʿba (ʿĀṣim’s second Rāwī) was more reliable than him in Qurʾān. Shuʿba complained once that Ḥafṣ took a book/notebook from him and never returned it, and that he used to take people’s books and copy them (an allusion to the criticism that Ḥafṣ used to take knowledge from books and claim it as his own). Some reported that Ḥafṣ was a better reciter than Shuʿba, but that he was a liar (kadhdhāb). Ibn Ḥibbān said that he used to forge and fabricate isnāds. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mahdī stated that it was not permissible to transmit ḥadīth from him (mā taḥill al-riwāya ʿanhu). (Ibid., 2:450–1)

3b) Abu Bakr Shu’ba

Abū Bakr Shuʿba: there were nine different statements about his real name. Consequently, he was listed under bāb al-kunā: man kunyatuhu Abū Bakr (those known as Abū Bakr) in Ibn Ḥajar’s Tahdhīb. Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal said that he was trustworthy, but that he made mistakes. Shuʿba used to boast and say: “I am one half of Islam” (anā niṣf al-Islām), in reference to his excellence in Qurʾānic recitation. Yaḥyā l-Qaṭṭān and Ibn al-Madīnī did not think highly of him, especially because he became senile and his memory deteriorated. He often made mistakes in ḥadīth, and his memory was not reliable when he delivered ḥadīth. Abū Nuʿaym stated that amongst his teachers, Abū Bakr Shuʿba was the most likely to make mistakes. (Ibid., 4:492–4)

4) Abū ʿAmr b. al-ʿAlā

There were almost no derogatory statements about Abū ʿAmr except the uncertainty surrounding his real name and his boasting that he had never met anyone who was more knowledgeable than himself. Abū Khaythama said that he could be trusted but he did not memorize much ḥadīth

4a) Duri

Al-Dūrī: Statements about him were generally positive, except for al-Dāraquṭnī, who stated that he was weak, without further specification. (Ibid., 1:454)

4b) Susi

Al-Sūsī: Statements about him were also positive, except for Maslama b. Qāsim, who deemed him to be weak without proof (bi-lā mustanad). (Ibid., 1:488–9.)

5) Ḥamza: al-Sājī

said that he was trustworthy, but his memorization was bad, and that he was not meticulous in transmitting ḥadīth. Some Ḥadīth scholars criticized his Reading and prohibited praying behind him, but Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal resented it without prohibiting such prayer. Abū Bakr Shuʿba said that the Reading of Ḥamza was considered to be bidʿa (innovation) amongst the community of the Qurrāʾ. Ibn Durayd stated: “I wish that Kūfa would be purified from the Reading of Ḥamza”

5a) Khalaf

Khalaf: Ibn Ḥanbal was asked about Khalaf and his consumption of alcohol. He answered that he was aware of this allegation but Khalaf was still a trustworthy, honorable individual. Khalaf allegedly said: “I repeated 40 years of prayers during which I had consumed alcohol according to the legal school of the Kūfans”. Yaḥyā b. Maʿīn said that Khalaf had no clue what Ḥadīth was.

5b) Khallad

Khallād: No negative statements were mentioned about him, and he did not feature in the major Ḥadīth biographical dictionaries. (Ibn al-Jazarī, Ghāya, 1:248.)

6) Nafi’

Nāfiʿ: Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal said that one could learn the Qurʾān from Nāfiʿ but not Ḥadīth. In another statement Aḥmad said that his ḥadīth was munkar. (Ibn Ḥajar, Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb, 4:207–8)

6a) Qalun

Qālūn: He was trustworthy in Qirāʾa, but not very much in Ḥadīth. Aḥmad b. Ṣāliḥ was asked about Qālūn’s trustworthiness in ḥadīth; he laughed and said: “Do you write down ḥadīth from anyone? Qālūn was deaf, but he was able to read people’s lips and correct their mistakes.” (Ibn Ḥajar, Lisān, 6:286–7.)

6b) Warsh

Warsh: He did not feature in Ḥadīth biographical dictionaries and there were no negative statements about him. (Ibn al-Jazarī, Ghāya, 1:446–7.)

7) Al-Kisāʾī

Ibn al-Aʿrābī praised al-Kisāʾī’s knowledge and said: He was the most knowledgeable of people, despite being a liar/impudent (rahaq). He used to consume alcohol and accompany young beautiful boys, yet he was a great Qurʾān reciter. It was related that one day he led some people in prayers and recited using Ḥamza’s System of recitation. After he finished the prayer, the people in the mosque beat him up with their fists and shoes. When asked why, he replied that it was because of the decadent/lowly Reading of Ḥamza (Qirāʾat Ḥamza al-radīʾa). (Abū ʿAbd Allāh Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 626/1229), Muʿjam al-udabāʾ, ed. Iḥsān ʿAbbās, 7 vols. (Beirut: Dār al-gharb al-islāmī, 1993), 4:1740–1.)

7a) Abū l-Ḥārith al-Layth b. Khālid & 7b) al-Dūrī

Abū l-Ḥārith al-Layth b. Khālid: No negative statements were mentioned about him. 7-b) al-Dūrī: Mentioned above in 4-a).

The Issue

Based on the biographical information provided, there appears to be a significant disconnect between the infallibility of the Quranic text and the documented fallibility of its key transmitters. The seven readers (qurrāʾ) and their transmitters, who were instrumental in establishing canonical Quranic recitation systems, demonstrate concerning patterns of unreliability in hadith transmission. Many of these authoritative figures were explicitly criticized by their contemporaries for having poor memory, making frequent mistakes, or being untrustworthy. For instance, Asim was described as having “bad memory,” while his transmitter Hafs was labeled a “liar” (kadhdhāb) who “used to forge and fabricate isnāds.” Leading scholars like Ahmad ibn Hanbal declared that Hafs’s hadith should not be transmitted at all. Similarly, Hamza’s recitation was considered an innovation (bidʿa) by other Quranic specialists, with Ibn Durayd wishing that “Kufa would be purified from the Reading of Hamza.”

The personal conduct of several readers and transmitters further undermines their reliability as well. Al-Kisai was described as “a liar” who “used to consume alcohol and accompany young beautiful boys,” while his transmitter Khalaf allegedly admitted to consuming alcohol during 40 years of prayers. Hisham bin Ammar became senile and “started to recite anything that was given to him,” reportedly transmitting “400 baseless hadīths.” Even Qunbul, a transmitter for Ibn Kathir, “grew corrupt” as police chief in Mecca and became “mentally unstable,” making numerous mistakes in recitation.

If these individuals were deemed unreliable for transmitting hadith, how could they simultaneously be trusted with the perfect transmission of the Quran itself? The biographical evidence suggests that the human elements in the chain of Quranic transmission were subject to the same fallibilities and weaknesses that affected their hadith transmission.

The Readers Broke The Rules

The following are examples cited by Dr. Van Putten from, “When the Readers Break the Rules Disagreement with the Consonantal Text in the Canonical Quranic Reading Traditions.”

While Ibn Mujahid, who canonized the first seven canonical reading traditions, does not explicitly state adherence to the rasm as a requirement, his selection of readers suggests it played a role. Al-Ṭabarī, a contemporary exegete, more explicitly rejected readings that did not conform to the rasm, indicating that it was a key factor in validating a recitation. By the time of Ibn al-Jazari, who formalized the canonical status of three additional readings, adherence to the rasm had become an explicit and fundamental criterion alongside grammatical correctness and sound transmission.

The motivations behind these deviations vary. Some readers altered the rasm to address perceived grammatical issues, while others followed variants found in different regional copies of the Quran. Additionally, differences emerged in the treatment of pronunciation in pausal (end-of-phrase) positions. Some deviations occurred in connected speech where the rasm reflected a pausal spelling, while in other cases, readers modified pronunciation in pausal contexts when the rasm reflected a non-pausal form.

The case of Abu Amr the grammarian further illustrates the tension between the claim of perfect Quranic preservation and the human reality of its transmission. As both a canonical reader and a respected Basran grammarian, Abu Amr stands out for making more deviations from the Uthmanic rasm (consonantal text) than any other canonical reader. This fact is particularly significant because his deviations appear to be motivated by grammatical concerns rather than faithful transmission of what he received.

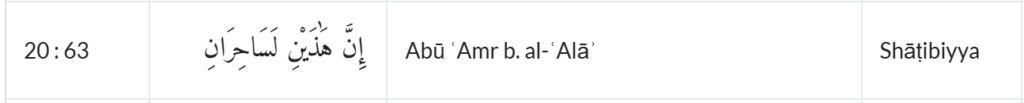

Q20:63-

قَالُوٓا۟ إِنْ هَٰذَٰنِ لَسَٰحِرَٰنِ يُرِيدَانِ أَن يُخْرِجَاكُم مِّنْ أَرْضِكُم بِسِحْرِهِمَا وَيَذْهَبَا بِطَرِيقَتِكُمُ ٱلْمُثْلَىٰ

The most notable example is his treatment of Q20:63 (نرحسلنذهنا), where he resolved a grammatically problematic construction by adding a letter not present in the Uthmanic rasm. The verse’s canonical reading “ʾinna hāḏāni la-sāḥirāni” contradicts Classical Arabic grammar rules, which require that ʾinna be followed by a noun in the accusative case. This awkwardness was recognized early on, with a tradition attributed to Aisha, the Prophet’s wife, explicitly calling it “an error of the scribes.” Rather than preserving the text as received, Abu Amr added a yāʾ to create “ʾinna hāḏayni la-sāḥirāni,” transforming it into grammatically correct Arabic. It seems more likely that this tradition attributed to Aisha was retroactively created in order to create the precedent to fix this grammatical mistake to begin with.

ʿUrwah questions: ʿĀʾishah about a number of verses:

4:162

lākin al-rāsikhūna fīʾl-ʿilm minhum

waʾl-muʾminūna yuʾminūna bi-mā unzila ilaika

wa mā unzila min qablik waʾl-muqīmīna

al-Ṣalāt waʾl-muʾtūna al-zakāt waʾl-muʾminūna

biʾllāhi waʾl-yawmʾl-ākhir ulāʾika sanuʾtīhim

ajran ʿaẓīman.

5:69

inna ʾlladhīna āmanū waʾlladhīna hādū

waʾl-ṣābiʾūna …

20:63

qālū: inna hādhāni la-sāḥirāni

ʿĀʾishah replied: ‘That was the doing of the scribes. They wrote it out wrongly.’

(Abdel Haleem,“Grammatical Shift for Rhetorical Purposes,” 424.)

Al-Suyuti provides a chain of transmission (isnad) for a tradition that attempts to address apparent grammatical irregularities in the Quranic text. This isnad reads: “Abu Mu’awiya narrated to us, from Hisham ibn ‘Urwah, from his father, that he asked ‘A’ishah.”

Upon closer examination, this chain of transmission suffers from multiple critical weaknesses that render the tradition unreliable by classical hadith standards. Abu Mu’awiya, a central transmitter in this chain, has been explicitly criticized by multiple authoritative hadith scholars, significantly undermining the reliability of this tradition.

- Imam al-Tirmidhi questioned Abu Mu’awiya’s reliability in certain narrations

- Ahmad ibn Hanbal expressed reservations about his transmission practices

- Al-Hakim al-Naysaburi documented concerns about his precision in hadith transmission

Perhaps even more damaging to this tradition’s credibility is its conspicuous absence from all six canonical hadith collections (al-kutub al-sitta). This omission is particularly telling, as the compilers of these collections – especially Bukhari and Muslim – attempted to apply their subjective rigorous standards for inclusion and would certainly have included such a tradition about Quranic textual history had they deemed it authentic. The weakness of this isnad creates a troubling scenario: a tradition with questionable authenticity is being employed to explain away a grammatical anomaly in what is purported to be a perfectly preserved text. This appears to be a post-hoc attempt to reconcile an apparent grammatical error in the Quranic rasm, rather than a reliable historical account of the text’s transmission.

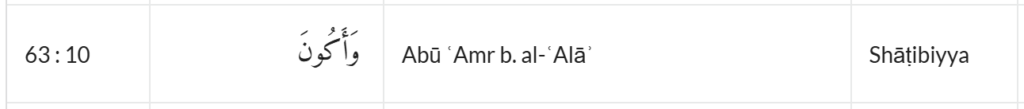

Q63:10

وَأَنفِقُوا۟ مِن مَّا رَزَقْنَٰكُم مِّن قَبْلِ أَن يَأْتِىَ أَحَدَكُمُ ٱلْمَوْتُ فَيَقُولَ رَبِّ لَوْلَآ أَخَّرْتَنِىٓ إِلَىٰٓ أَجَلٍ قَرِيبٍ فَأَصَّدَّقَ وَأَكُن مِّنَ ٱلصَّٰلِحِينَ

Abu Amr’s handling of Q63:10 provides another striking example of a canonical transmitter prioritizing grammatical correctness over strict adherence to the Uthmanic rasm. In this verse, while all other readers maintained the grammatically problematic apocopate form “wa-ʾakun” (and be) following a subjunctive verb, Abu Amr modified the text by adding a wāw to create “wa-ʾakūna,” making it grammatically consistent with the preceding subjunctive verb.

This intervention is particularly telling because it directly parallels another verse (Q28:47b) where both verbs correctly appear in the subjunctive form. Even classical grammatical exegetes struggled to explain the inconsistency in Q63:10, with Ibn Khalawayh attempting an unconvincing grammatical justification that ignored the presence of the fa- particle that necessitates the subjunctive. The simplest explanation—that the rasm itself contained a grammatical error—was apparently unacceptable within the theological framework of perfect textual preservation.

Abu Amr’s decision to “correct” the text reveals a fundamental contradiction in the transmission process. If the Quranic text was truly preserved exactly as revealed, then Abu Amr committed a serious transgression by altering it based on his grammatical judgment. Conversely, if Abu Amr was justified in making such corrections, then the premise of perfect preservation becomes untenable. The fact that his “corrected” reading became canonized as one of the valid ways to recite the Quran further complicates the traditional narrative.

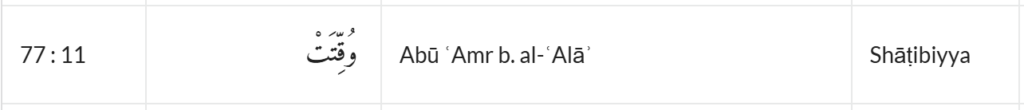

Q77:11

وَإِذَا ٱلرُّسُلُ أُقِّتَتْ

Abu Amr’s treatment of Q77:11 provides yet another example of his willingness to deviate from the Uthmanic rasm to maintain grammatical consistency within the Quranic corpus. In this case, while most readers followed the rasm and pronounced تتقا as “ʾuqqitat” (the time was set), Abu Amr chose to ignore the written text and instead recite it as “wuqqitat.” This intervention is particularly revealing because it shows Abu Amr prioritizing systematic grammatical patterns over the letter of the text. Throughout the Quran, similar verbal forms consistently maintain their initial “wu” or “wū” sounds, as seen in Q13:35 (wuʿida), Q3:25 (wa-wuffiyat), and Q7:20 (wūriya). The unique shift to “ʾu” in Q77:11 represented an anomaly that apparently troubled Abu Amr enough to warrant correcting it against the rasm.

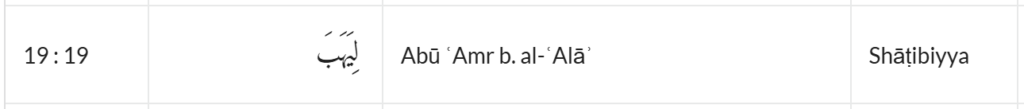

Q19:19-

قَالَ إِنَّمَآ أَنَا۠ رَسُولُ رَبِّكِ لِأَهَبَ لَكِ غُلَٰمًا زَكِيًّا

Abu Amr’s handling of Q19:19 reveals yet another dimension of how human judgment influenced Quranic transmission, this time potentially for theological rather than grammatical reasons. Here, the verse in the Uthmanic rasm (امنا ايكزاملغكلبهالكبرلوسرانا) was read by most canonical readers as “ʾinnamā ʾana rasūlu rabbiki li-ʾahaba laki ġulāman zakiyyan” – “I am but a messenger of your Lord, [sent] so that I might give you a pure son.”

The first-person verb “li-ʾahaba” (that I give) created theological discomfort as it could be interpreted to suggest that the spirit (Gabriel) would impregnate Mary rather than God directly causing the conception. This apparent theological problem troubled early exegetes, with al-Farra feeling compelled to explain that “The giving is by God, but Gabriel told it to her as if he were the giver.”

Rather than maintaining this potentially problematic reading, Abu Amr again deviated from the rasm, opting instead for “li-yahaba” (that he give) in the third person, thereby removing any suggestion that Gabriel might be the agent of Mary’s conception. Two other prominent readers—Nafi of Medina and Ya’qub of Basra—followed his lead in this deviation. While Abu Amr might have justified this change through a grammatical technicality (the potential homophony of li-ʾahaba and li-yahaba in dialects that drop the glottal stop), the motivation appears primarily theological.

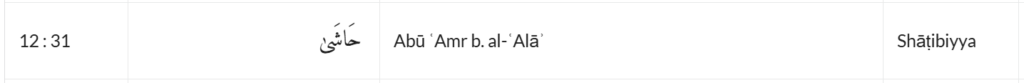

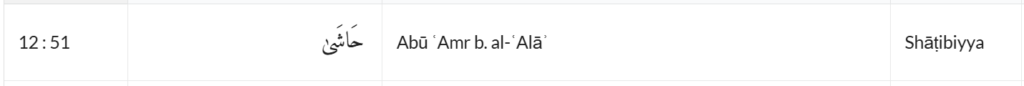

Q12:31, 51-

12:31- فَلَمَّا سَمِعَتْ بِمَكْرِهِنَّ أَرْسَلَتْ إِلَيْهِنَّ وَأَعْتَدَتْ لَهُنَّ مُتَّكَـًٔا وَءَاتَتْ كُلَّ وَٰحِدَةٍ مِّنْهُنَّ سِكِّينًا وَقَالَتِ ٱخْرُجْ عَلَيْهِنَّ فَلَمَّا رَأَيْنَهُۥٓ أَكْبَرْنَهُۥ وَقَطَّعْنَ أَيْدِيَهُنَّ وَقُلْنَ حَٰشَ لِلَّهِ مَا هَٰذَا بَشَرًا إِنْ هَٰذَآ إِلَّا مَلَكٌ كَرِيمٌ

12:51- قَالَ مَا خَطْبُكُنَّ إِذْ رَٰوَدتُّنَّ يُوسُفَ عَن نَّفْسِهِۦ قُلْنَ حَٰشَ لِلَّهِ مَا عَلِمْنَا عَلَيْهِ مِن سُوٓءٍ قَالَتِ ٱمْرَأَتُ ٱلْعَزِيزِ ٱلْـَٰٔنَ حَصْحَصَ ٱلْحَقُّ أَنَا۠ رَٰوَدتُّهُۥ عَن نَّفْسِهِۦ وَإِنَّهُۥ لَمِنَ ٱلصَّٰدِقِينَ

Abu Amr’s treatment of “ḥāšā li-llāhi” (God forbid) in Q12:31 and Q12:51 reveals another instance where a canonical reader modified the Quranic text to align with evolving Arabic linguistic norms. The Uthmanic rasm spells this expression as هللشح, lacking the final long vowel ā. While all other readers followed the rasm and pronounced it as “ḥāša li-llāhi” with a final short vowel, Abu Amr opted to pronounce it according to what became the normative Classical Arabic form, “ḥāšā li-llāhi.”

Abu Amr’s decision to “update” the pronunciation to match contemporary usage rather than maintain the presumably more ancient form shows his willingness to modernize the text according to the linguistic standards of his time. Abu Amr maintained a compromise position by following the rasm in the pausal form (pronouncing it as “ḥāš” at the end of a phrase) while ignoring it in connected speech. This nuanced approach suggests that even as he felt empowered to modify the pronunciation, he still acknowledged some obligation to the written text, particularly in pausal positions where the rasm was considered especially authoritative.

By the time later grammarians commented on this pronunciation, Abu Amr’s version had become the Classical Arabic norm, forcing them to justify the other readers’ adherence to the rasm as a conscious decision to “be satisfied with the fatḥah” and “follow the black writing” rather than as a preservation of the original form

Abu Amr – ‘Editing God’s Word’

Abu Amr’s systematic alterations to the Quranic text represents a big hit to claims of perfect textual preservation. As both a canonical reader and respected Basran grammarian, he consistently modified the Uthmanic rasm whenever he encountered what he perceived as grammatical, phonological, or theological problems. He added a yāʾ to Q20:63 to fix a case agreement issue with “ʾinna hāḏāni,” inserted a wāw in Q63:10 to harmonize the apocopate “wa-ʾakun” with the preceding subjunctive verb, corrected the anomalous “ʾuqqitat” to the more consistent “wuqqitat” in Q77:11, changed the first-person “li-ʾahaba” (that I give) to third-person “li-yahaba” (that he give) in Q19:19 to resolve theological concerns about Gabriel impregnating Mary, and modernized the archaic “ḥāša li-llāhi” to the Classical Arabic “ḥāšā li-llāhi” in Q12:31 and Q12:51.

These interventions reveal that even the most authoritative transmitters of the Quran felt empowered to correct what they viewed as errors or inconsistencies in the text. If Abu Amr, one of the seven canonical readers whose transmissions are considered divinely sanctioned, believed the Uthmanic rasm contained mistakes requiring his correction, this fundamentally undermines the theological claim that the Quran has been perfectly preserved. His editorial approach demonstrates that the transmission process involved active human judgment rather than mechanical reproduction, with transmitters—whose unreliability in hadith transmission is well-documented—making decisions about what constituted the “correct” reading based on their own expertise, preferences, and theological concerns. The canonization of Abu Amr’s corrected readings is an irreconcilable contradiction: either the Uthmanic rasm contained errors that needed correction (negating claims of perfect preservation), or Abu Amr committed serious transgressions by altering divine revelation (undermining the authority of the canonical readers themselves).

Additional Readings

Proof of Asim’s fabrications:

Excellent Excellent work. Praise God.

Excellent Excellent work. Praise God.