Fabricated Hadith Prophecy: THE PROPHESIED RETURN OF DHUL-KHALASA

“‘I swear by God, I have a plan to deal with your statues, as soon as you leave.’ He broke them into pieces, except for a big one, that they may refer to it.””

-Quran 21:57-58

The Hadith in Question:

The Prophet said: “The Hour will not be established till the buttocks of the women of the tribe of Daus move while going round Dhi-al-Khalasa.”

The Argument

This apologetic argument centers on a prophecy attributed to the Prophet Muhammad regarding the revival of idolatry in Arabia, specifically the return of the cult of Dhul-Khalasa, and claims its fulfillment centuries later. It begins by establishing the historical context of pre-Islamic Arabia, where the Islamic tradition believes idolatry was widespread, and Dhul-Khalasa, known as “the Kaaba of Yemen,” was a major idol worshiped by the Arabs. With the rise of Islam, the Muslims sought to eradicate idolatrous practices, including the cult of Dhul-Khalasa, which involved prostitution and other immoral rituals. The argument then introduces the prophecy, in which the Prophet reportedly foretold that idolatry, particularly the cult of Dhul-Khalasa, would return in the future, with the women of the tribe of Daus engaging in idolatrous practices around Dhul-Khalasa as a sign of the approaching Hour (the end times).

The argument then argues that this prophecy was fulfilled in the 1800s when these idols started to resurface in Arabia, which culminated in the discovery of a massive building dedicated to the same idol within the same region. This building, along with a worshiped tree, was reportedly used by the tribe of Daus to revive the prostitution cult associated with Dhul-Khalasa. The campaign to destroy the idol and its temple is presented as evidence of the prophecy’s fulfillment, with emphasis on the size of the structure and the effort required to dismantle it. The argument concludes by asserting that the destruction of Dhul-Khalasa’s temple and the eradication of the cult once again align with the Prophet’s warning, thereby validating the prophecy. This narrative is used to support the claim of the Prophet’s foresight and the truth of Islamic teachings.

The Faulty Logic and Fallacies

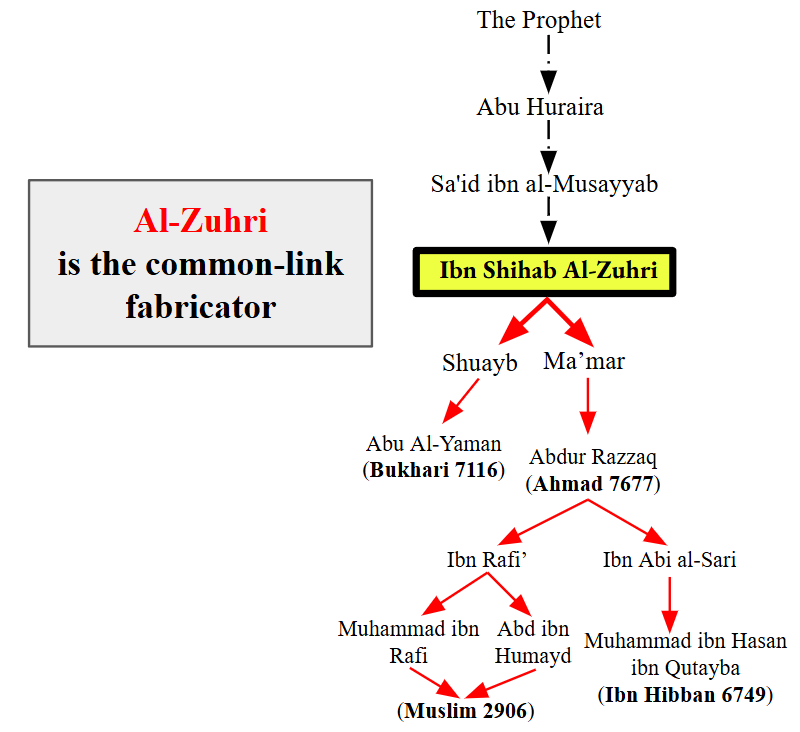

The transmission history for this narration is not promising for the apologist. Essentially, we have a common-link of Al-Zuhri claiming to have received this narration from Sa’id. At this point, this narration is simply a ‘trust me bro’ isnad past Al-Zuhri. Can we just trust Al-Zuhri? Well, he did this with the previous prophecy in the fire of hijaz. Something interesting that we have, is that we have an alternative isnad that is close to what Al-Zuhri has, but doesn’t go through him. It’s a non-prophetic narration linked to Abdullah ibn Amr that has the same prophecy, except it’s not linked to the prophet.

١٤٠٠ – حدثنا الوليد عن الحارث بن عبيدة عن رجل عن عبد الرحمن بن سلمان

عن عبد الله بن عمرو قال إذا عبدت ذو الخلصة صنم كان لدوس في الجاهلية كان ظهور الروم على الشام

Translation:

1400 – Al-Walid narrated to us from Al-Harith bin Ubaydah, from a man, from Abdur-Rahman bin Salman, from Abdullah bin Amr, who said:

“When Dhul-Khalasa, an idol that belonged to the Daws tribe in the pre-Islamic era, is worshiped, it will be a sign of the Romans’ dominance over al-Sham (Greater Syria).”

١٣٣٣ – حدثنا الوليد عن الحارث بن عبيدة عن عبد الرحمن بن سلمان

عن عبد الله بن عمرو قال إذا عبدت ذو الخلصة كان ظهور الروم على الشام

Translation:

1333 – Al-Walid narrated to us from Al-Harith bin Ubaydah, from Abdur-Rahman bin Salman, from Abdullah bin Amr, who said:

“When Dhul-Khalasa is worshiped, it will be a sign of the Romans’ dominance over al-Sham (Greater Syria).”

١٦٣٣ – حدثنا ابن وهب عن ابن لهيعة والليث بن سعد عن خالد بن يزيد بن سعيد عن أبي هلال عن أبي سلمة عن عبد الله بن عمرو قال بعد ما يهدم الناس مع عيسى بن مريم عليه السلام زمانا تقبل ريح بياتية مسها مس الحر وريها ريح المسك فتستخرج روح كل مسلم ثم يقول الناس متى نحن على هذا الدين حتى يرجعون إلى دين الآباء حتى يعبدوا ما كان يعبد آباؤهم فذلك

قال أبو هريرة كأني بنساء دوس قد اصطفقن على ذي الخلصة

Translation:

1633 – Ibn Wahb narrated to us from Ibn Lahi’ah and Al-Layth bin Sa’d, from Khalid bin Yazid bin Sa’id, from Abu Hilal, from Abu Salama, from Abdullah bin Amr, who said:

“After people live for a time following Jesus, the son of Mary, peace be upon him, a night breeze will come whose touch is like heat, but its scent is like musk, and it will take the soul of every Muslim. Then people will say: ‘When were we ever on this religion?’ until they return to the religion of their forefathers and worship what their ancestors worshiped.”

Abu Huraira said: “It is as if I can see the women of Daws gathered around Dhul-Khalasa.“

Abdullah ibn Amr

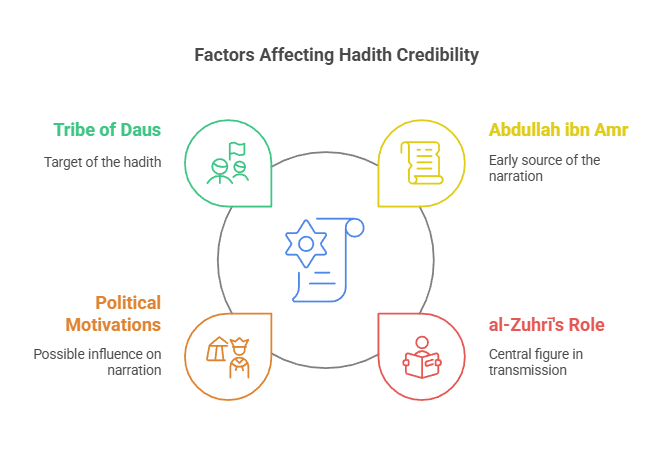

As can be seen, the earliest renditions of these narrations don’t even trace back to the prophet, they trace back to Abdullah ibn Amr, in the same case as the Siege of Baghdad. The transmission history of this narration further weakens its credibility and exposes significant issues for the apologist. The primary chain of transmission relies heavily on al-Zuhrī, who serves as the common link for the prophetic version of the hadith. However, al-Zuhrī’s reliability is highly suspect. He was a court scholar for the Umayyads, a dynasty known for using religious narratives to legitimize their rule and suppress dissent. His role as a transmitter raises the possibility of political motivations behind the hadith, particularly one that targets the tribe of Daus, who had a history of resistance to central authority. Essentially, the isnad (chain of transmission) past al-Zuhrī boils down to a “trust me bro” situation, as there is no independent verification of his claim to have received this narration from Saʿīd ibn al-Musayyib. Given al-Zuhrī’s track record—such as his involvement in transmitting the dubious “Fire of Hijaz” prophecy—his credibility is far from assured.

What makes this even more problematic is the existence of alternative chains of transmission that do not go through al-Zuhrī and do not attribute the prophecy to the Prophet Muhammad. Instead, these chains trace back to ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAmr, a companion known for his knowledge of previous scriptures and eschatological traditions. In these versions, the prophecy about Dhū al-Khalaṣah is presented as a statement by ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAmr, not as a divine revelation from the Prophet. The transmission history of this narration is deeply problematic for the apologist. The reliance on al-Zuhrī, a politically motivated transmitter, undermines the hadith’s authenticity. The existence of earlier, non-prophetic versions traced back to ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAmr suggests that the prophecy originated as a speculative or tribal warning rather than a divine revelation. The later attribution to the Prophet appears to be an attempt to elevate the prophecy’s status, a common practice in early Islamic historiography. This evidence collectively weakens the case for the prophecy’s legitimacy and further supports the conclusion that it is a fabrication rather than a genuine prophetic tradition.