Following the Yasir Qadih incident, where he admitted, “Nobody in the academy affirms the Muslim Sunni science of hadith. Nobody. It is considered to be completely discredited. I’m just being factual.” A Sunni Imam by the name of “Dr. Shadee Elmasry,” posted a response addressing this hadith controversy. In this response, he details several purported flaws in the Western epistemology of Hadith. A closer examination of his claims against the backdrop of academic scholarship proves significant distortions, mischaracterizations, and strawman arguments.

Below, we dissect Dr. Elmasry’s central arguments, providing the actual transcript sections and an analysis of his inaccuracies.

Western Epistemology is Inherently Biased

Transcript Timestamp: 00:00:32–00:02:08

Dr. Shadee Elmasry’s Argument Summary:

The Western historical method is not neutral. It comes with its own theological and philosophical biases, just like any other tradition. The idea that we should adopt their critical approach to hadith is flawed because their epistemology is based on materialism, skepticism, and anti-religious presumptions.

Dr. Elmasry constructs a reductive caricature of what he calls “the Western epistemology.” He portrays it as:

- Inherently atheistic

- Born from anti-Church trauma

- Motivated by the idea that “everyone lied to us”

This characterization is deeply misleading and a blatant straw man. The actual academic critical method used in historical and hadith studies is not an atheistic manifesto — it’s a methodological posture that withholds metaphysical assumptions (not denies them). Historians suspend judgment on supernatural claims not because they are “anti-religion,” but because the historical method by definition works with publicly accessible evidence. Even Dr. Joshua Little, an Oxford-trained scholar in Islamic history and a practitioner of the very method Elmasry criticizes, talks about this in his own words:

“Like, let me put a different way. I’m not ruling out miracles. I’m not ruling out God. I’m not ruling out prophecy. I’m not ruling out any of that. I’m happy. At least you know, maybe there are some. Well, whatever. I’m happy to concede. For the sake of argument that prophecy is possible. Miracles are possible. Other kinds of supernatural things are possible. I’ll grant it all. The argument still stands because it’s not based on an a-priori rejection of those things. This is completely untrue.“

“Oxford Scholar Dr. Joshua Little Gives 21 REASONS Why Historians are SKEPTICAL of Hadith by Dr. Javad T. Hashmi”

Therefore, the idea that Western hadith criticism is driven by a rejection of the unseen is false — methodological agnosticism is not equivalent to metaphysical disbelief.

Genetic Fallacy – Dismissing a Method Because of a Potential Origin

Transcript Timestamp: 00:02:08–00:03:41

Dr. Shadee Elmasry’s Argument Summary:

The Western historical method originated during the Renaissance and Enlightenment because people were reacting to lies and corruption by the Church — like fake relics and documents attributed to apostles that were actually forgeries. Because of this, Western thinkers developed a critical view of religious history. Their motivation was rooted in betrayal and trauma. Therefore, their entire approach is built on the presumption that historical religious claims are suspicious, false, or invented.

Dr. Elmasry claims:

- The Western historical-critical method originated in the Renaissance/Enlightenment as a reaction to Church corruption and forgeries.

- The method was not motivated by intellectual integrity, but by betrayal and psychological distrust.

- Therefore, its entire epistemological foundation is tainted by skepticism and anti-religious assumptions.

Once more, Elmasry assumes that the motivation or historical context behind the development of a method invalidates its content or usefulness. The critical method partly arose out of skepticism toward forged relics, false attributions, and papal claims in Europe. That does not mean its conclusions or methodology are invalid by association. Dr. Elmasry paints a cartoon version of intellectual history, as if a few disillusioned Christians in the Renaissance got mad at fake relics and emotionally birthed an entire academic field out of spite. If we followed this logic consistently, then Islamic hadith science would also be suspect — after all, it arose precisely because of widespread fabrication in the early Islamic period. The isnād system, rijāl criticism, and principles of jarḥ wa-taʿdīl were developed in response to deception. But no serious Muslim scholar would claim that this reactionary context renders the entire discipline invalid.

Ironically, some of the early defenders of Islamic hadith, like Ibn Ḥibbān or al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, made exactly the same move — they introduced harsher scrutiny to preserve authenticity, not undermine religion. So Elmasry’s logic, if applied consistently, would also dismantle his own tradition’s methodology. Elmasry avoids engaging with the content of modern historical tools. He reduces centuries of layered scholarship into a shallow reading: “They got lied to, so now they [‘Orientalists’] think everyone’s lying.” Dr. Elmasry’s claim that Western historical criticism is invalid because it emerged in a context of betrayal is logically unsound, historically inaccurate, and selectively applied. If you follow his reasoning through, it would dismantle his own tradition, too. What matters is not why a method started, but how it functions, how rigorous it is, and how it stands up under scrutiny.

Projection onto Other Civilizations

Transcript Timestamp: 00:03:41–00:04:46

Dr. Shadee Elmasry’s Argument Summary:

They repeat the same thing. They say, ‘Well, the Muslims are just like us. They made up all these stories. They fabricated these miracles. They’re all liars.’ Because in Europe, they were liars. In Europe, they made up these relics and said that they belonged to saints. In Europe, they forged documents. So they assume everyone else did the same thing.

Dr. Elmasry constructs a reductive caricature of what he calls “the Western epistemology.” He portrays it as:

- A form of intellectual projection: Western scholars, having experienced deception within their own religious traditions, supposedly project this experience onto other civilizations, assuming Muslims also fabricated religious texts and stories.

- Motivated by a cynical generalization: Because European history had instances of forged relics and documents, Western scholars allegedly conclude that all religious traditions, including Islam, must operate on the same principle of widespread deception.

This argument is a straw man combined with an appeal to motive fallacy. Dr. Elmasry misrepresents the academic approach as a form of petty, vindictive projection rather than an actual systematic methodology. Academic historians, whether studying European, Islamic, or any other history, do not begin with the assumption that “everyone is lying.” Instead, they apply methodological skepticism, a critical stance that requires evidence and corroboration for claims, regardless of their origin. This is inherent in historical inquiry, which seeks to reconstruct past events based on verifiable data.

For instance, scholars like Patricia Crone, Michael Cook, and John Wansbrough, often cited as Western critical scholars of early Islam, developed their approaches not from an a priori assumption of “Muslims are just like us and therefore lied,” but by applying established methods of textual criticism and historical analysis to the early Islamic sources themselves. Their conclusions, whether you agree with them or not, are based on internal inconsistencies, anachronisms, and comparisons with external evidence, not on a simplistic projection of “European historical experiences”.

Dismissal of Academic Consensus as “Orientalism” or “Imperialism”

Transcript Timestamp: 00:04:46–00:06:15 (Approximate – this section often follows the projection argument)

Dr. Shadee Elmasry’s Argument Summary:

They call it ‘Orientalism’ or ‘academic imperialism.’ They’re trying to impose their worldview on us. They want to tear down our tradition because they couldn’t keep their own. This is nothing more than a new form of colonialism.

Dr. Elmasry’s argument asserts that:

- Western academic scholarship on Islam is inherently “Orientalist” or “imperialist,” and this framing suggests that the primary motivation behind critical hadith studies is not scholarly inquiry but a desire to undermine Islamic tradition and assert Western intellectual dominance.

- It’s a form of intellectual envy or revenge. Western scholars, having allegedly failed to preserve their own religious traditions from critical scrutiny, now seek to dismantle Islam out of spite or a misguided sense of superiority.

This is a classic example of an ad hominem fallacy combined with a conspiracy theory. By labeling academic scholarship as “Orientalism” or “imperialism,” Dr. Elmasry avoids engaging with the substantive arguments and evidence presented by scholars. To dismiss critical scholarship as “academic imperialism” implies a lack of intellectual agency within the academic world and a simplistic view of academic motivations. Scholars engage in critical inquiry because it is the foundation of knowledge production. They follow evidence, test hypotheses, and peer-review their work, regardless of their personal faith or background. The goal is not to “tear down” traditions but to understand them more thoroughly based on available evidence.

Misrepresenting the “Satanic Verses” Episode

Transcript Timestamp: 00:06:16–00:07:12

Dr. Shadee Elmasry’s Argument Summary:

“If the Prophet ﷺ had actually uttered the so-called ‘Satanic Verses’—which refers to the claim that Satan whispered certain verses to the Prophet ﷺ while he was reciting and receiving revelation—then Jibrīl supposedly returned to the Prophet ﷺ and said: ‘O Muhammad, that was not part of the revelation.’ Now hold on a second—if that really happened, wouldn’t the disbelievers (kuffār) have brought it up? Wouldn’t other Companions have talked about it?

The story claims that the Prophet ﷺ was allegedly sitting at the Kaʿbah when this occurred. So no, it’s not accepted.

As a side note, here’s the amazing part: this fabricated story—this lie about the Prophet ﷺ—is actually refuted within the Quran itself, and it serves as a proof of its divine origin. Why? Look at the second verse of Sūrat al-Najm:

“Your companion [Muḥammad] has neither strayed nor erred.”

Literally, the first verse after the opening oath is a divine defense of the Prophet ﷺ against exactly this kind of lie.”

Dr. Elmasry’s assertion is demonstrably false, not just in historical detail, but in methodological honesty. His claim that the incident is based on “one weak report” completely erases centuries of Islamic scholarship, including mainstream Sunni scholars, who not only reported the event but in many cases accepted it — even finding theological meaning in it.

Dr. Elmasry never once acknowledges the existence of Shahab Ahmed’s entire book-length study, Before Orthodoxy: The Satanic Verses in Early Islam, which meticulously compiles and analyzes over 50 different isnāds (chains of transmission) for this single event. These aren’t from some obscure Shīʿī fringe — they’re from:

- Ibn ʿAbbās

- Saʿīd b. Jubayr

- ʿIkrimah

- Abū al-ʿĀliyah

- Qatādah

- al-Ḍaḥḥāk

- Muqātil

- al-Kalbī

- And even reported in ʿUrwah b. al-Zubayr’s maghāzī

In other words, this isn’t “one fabricated narration.” It’s a multi-strand tradition spanning Companions, Tābiʿūn, early exegetes, and historians.

Dr. Elmasry claims early scholars wouldn’t have accepted such a thing. That is demonstrably untrue.

Ibn Taymiyyah, often cited as a bastion of traditional orthodoxy, affirms the incident as historically credible in Majmūʿ al-Fatāwā:

“The early Islamic scholars (salaf) collectively considered the verses of the cranes in accordance with the Quran. And from the later scholars (khalaf) who followed the opinion of the early scholars, they say that these traditions have been recorded with authentic chains of narration and it is impossible to deny them, and the Quran itself testifies to it.”

— Majmūʿ al-Fatāwā, vol. 10

This refers to Quran 22:52:

“We never sent a messenger or prophet before you except that when he recited, Satan cast into his recitation. But God abolishes what Satan casts…”

So contrary to Elmasry’s claims:

- Early scholars didn’t see the incident as an insult to the Prophet.

- They saw it as a test, consistent with the Quranic pattern of divine correction.

- It was cited to reinforce the Prophet’s truthfulness, not deny it.

It was cited to reinforce the Prophet’s truthfulness, not deny it. Early Muslim scholars didn’t try to hide this story. In fact, many of them saw it as something that confirmed the Prophet’s honesty and the truth of the Quran. Shahab Ahmed shows in Before Orthodoxy that this story was told through over 50 different chains of narration, and it was accepted by major early scholars. They didn’t see it as blasphemy — they saw it as a test from God, just like Quran 22:52 says: Satan may try to interfere, but God removes what he throws in and makes His message clear. This wasn’t some rare or fringe report. Famous scholars like al-Ṭabarī, Ibn Saʿd, Ibn Isḥāq, al-Zamakhsharī, and al-Bayḍāwī included the story in their tafsīr and sīrah books. Shahab Ahmed explains:

“The Satanic Verses was not a marginal or obscure episode; it was recorded, transmitted, and commented upon by central figures in the formation of the Islamic scholarly tradition.” (Before Orthodoxy, p. 48)

So Dr. Elmasry’s claim that no one accepted it is just not true. His view reflects a modern reaction, not the position of the early generations. Even Ibn Hajar, though uncomfortable with the story, still included it in his works because it was too widespread to ignore. Also, his point that “the kuffār or companions would have talked about it if it happened” doesn’t make sense — because the reports literally say that the pagans did talk about it. They praised the Prophet when he recited those lines, thinking he had finally acknowledged their gods. That’s part of why the verse was corrected right away.

So instead of dealing with this huge body of evidence, Elmasry just brushes it off as a lie. But the same hadith science he defends is the one that preserved this story with multiple isnāds from multiple early figures. Ignoring all of that doesn’t protect hadith sciences — it selectively uses them when convenient.

When ʿIlm al-Rijāl Backfires

Dr. Elmasry claims the Satanic Verses incident is a lie based on “one weak narration,” but this is misleading and methodologically inconsistent. If we actually apply the same hadith sciences that he defends — especially the criteria of Bukhārī, Muslim, and later critics like Ibn Ḥajar and al-Dhahabī — we find that many versions of the Satanic Verses report pass those very standards.

1. al-Ṭabarī’s Isnād:

Ibn ʿAbbās → Saʿīd ibn al-Musayyab → al-Zuhrī → Muʿammar ibn Rāshid

Evaluation According to Bukhārī/Muslim Criteria:

| Criterion | Status |

|---|---|

| Continuous chain | Yes |

| All narrators thiqa | Yes – all are top-tier narrators |

| Direct transmission established | Yes – known overlap in lifetime and locality |

| No ʿillah (hidden defects) | None reported in major rijāl works |

| No shudhūdh (conflict) | No contradiction with more authentic reports |

2. Multiple Isnāds via Saʿīd ibn Jubayr:

One of the strongest isnāds:

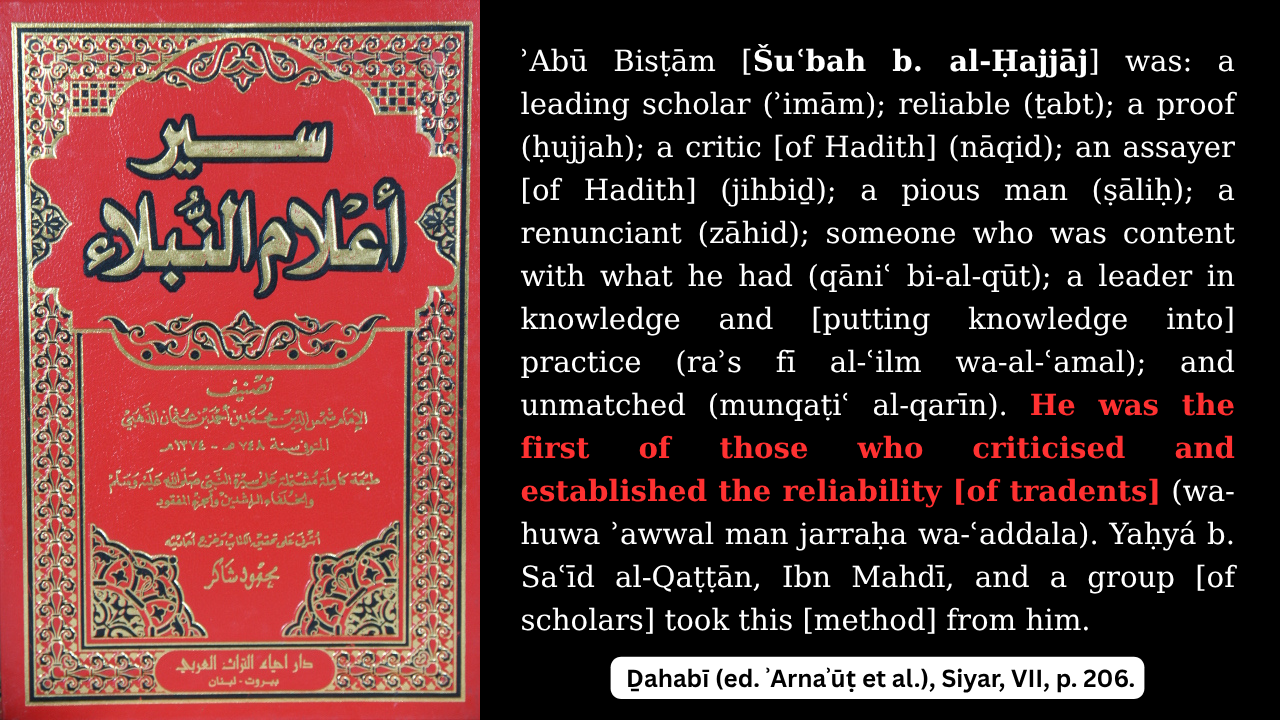

Ibn ʿAbbās → Saʿīd ibn Jubayr → Abū Bishr Jaʿfar → Shuʿbah ibn al-Ḥajjāj

Other variants (in Tafsīr works):

Ibn ʿAbbās → Saʿīd ibn Jubayr → ʿUthmān ibn al-Aswad

| Criterion | Status |

|---|---|

| Reliable narrators | Ibn ʿAbbās and Saʿīd ibn Jubayr are both thiqa |

| Shuʿbah ibn al-Ḥajjāj | One of the most reliable early hadith transmitters |

| Multiple corroborating isnāds | Found in al-Ṭabarī, al-Wāḥidī, al-Bazzār, Ibn Mardawayh |

| Consistency of content | Yes, with minor matn variation |

Dr. Elmasry’s claim that the Satanic Verses relies on “one weak narration” fails under scrutiny:

- Shahab Ahmed documents dozens of chains (riwāyāt 1–50), many with reliable narrators.

- Several satisfy the criteria later scholars applied to Ṣaḥīḥayn collections.

- To reject them while defending other similarly transmitted hadiths is inconsistent.

Hadith Science is the Most Rational & Accurate Historical Method

Elmasry’s Claim:

“Hadith is based on rational inquiry… It’s the most thorough history you’re going to find in any subject…”

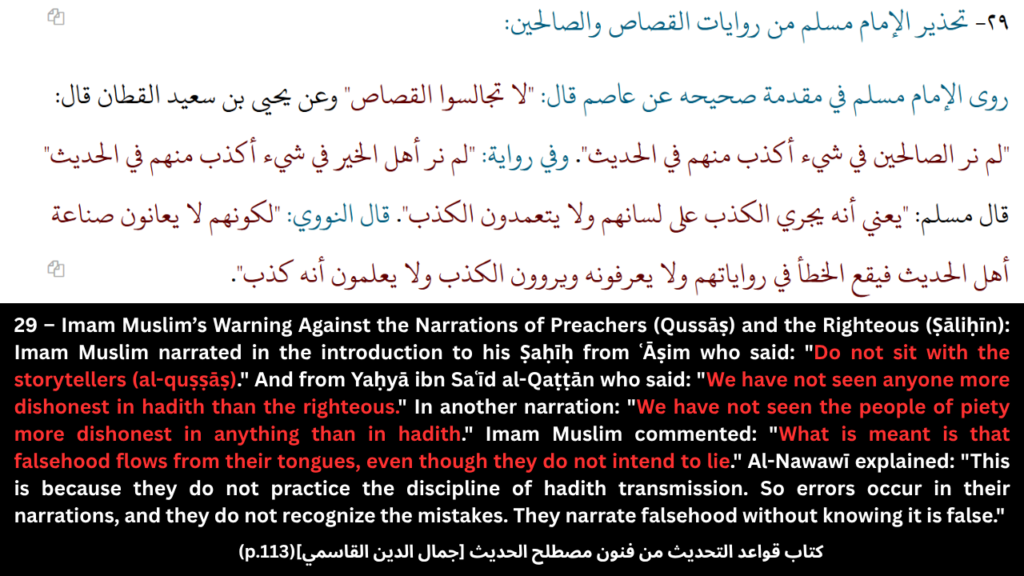

Dr. Elmasry says that hadith is “the most thorough history you’re going to find in any subject.” That’s a big claim. And on the surface, it sounds impressive — all those names, dates, biographies of transmitters. But once you actually look under the hood, the picture isn’t nearly as solid as he wants people to believe.

The core of hadith science is the isnād system, the chains of narration that trace who said what, and who heard it from whom. And that sounds objective, but the system assumes that the early generations — the Prophet’s companions and the generation right after — were all trustworthy by default. Not because we can independently verify every one of them, but because the scholars said so. That’s baked into the system: “All the companions are upright.” But this assumption runs straight into the Quran. In Surah 9:101, God tells the Prophet:

“Among the Arabs around you are hypocrites, as well as among the people of Medina. You do not know them — We know them.” (Quran – 9:101)

That’s massive. It means the Prophet himself couldn’t always tell who around him was sincere and who was lying. So how are later scholars supposed to know for sure which companions or early transmitters were always truthful, just by reading reports about them generations later? The Quran literally warns that some hypocrites blended in, looked sincere, and even lived in Medina — right under the Prophet’s nose. So the idea that everyone in the earliest generation was pure and trustworthy isn’t just historically weak — it contradicts the Quran. And beyond that, the method focuses almost entirely on the isnād instead of the content. So if the chain checks out, the actual hadith can be accepted even if the content is strange, unrealistic, or contradicts other reports. That’s how we end up with sahih hadiths about Adam being 90 feet tall, or eating 7 ajwa dates to avoid poison and magic. If the narrators were deemed reliable, the story would get through. Matn (content) criticism has always been secondary.

And let’s be honest, if Christians came forward today with a fully developed system like ʿilm al-rijāl, complete with chains of transmission and biographies of early Church fathers, no Muslim scholar would accept it as proof that the Gospels are historically reliable or divinely preserved. They wouldn’t care how many chains there are or how upright the narrators were said to be because Muslims reject the core theological claims those texts contain — like the claims about Jesus or the authority of the Pope — regardless of how well the tradition was preserved. Even if Catholics claimed, “We have an unbroken chain of trustworthy scholars validating papal authority,” Muslim scholars would still dismiss it outright. So why should anyone outside the Islamic tradition feel obligated to accept the same logic when applied to hadith? You can’t demand epistemic charity for your own tradition while denying it across the board to others.