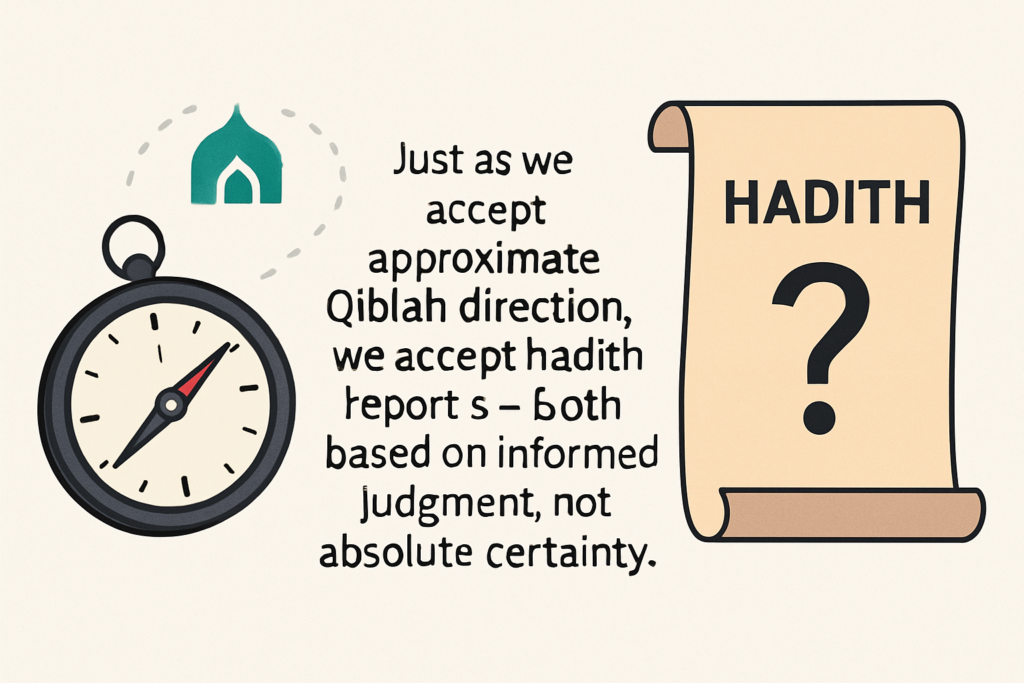

Al-Shāfiʿī argues that since Islamic law permits acting on probabilistic knowledge (zann) in areas where certainty is unattainable (such as determining the Qiblah direction, estimating equivalence in blood money, or relying on witness testimony), we should also accept solitary hadith reports (khabar al-āḥād), even if they lack certainty. He claims that as long as a scholar applies proper ijtihād (effortful reasoning based on the Quran, Sunnah, and consensus), acting on such probabilistic reports is justified. Rejecting hadith due to their uncertainty would logically require rejecting all judgments based on analogy, expert testimony, or probability, which would render legal reasoning impossible.

Al-Shāfiʿī refers to the verse about murder and expiation (4:92), which discusses the compensatory judgment for accidental killing and that judges must assess the equivalent value, even though exact equivalence can’t be known. This requires ijtihād (human judgment), not certainty. Below are a few verses that similarly require ijtihād, where definitive conclusions are not possible.

4:92 – Accidental Killing & Diya (Blood Money)

[4:92] No believer shall kill another believer, unless it is an accident. If one kills a believer by accident, he shall atone by freeing a believing slave, and paying a compensation to the victim’s family, unless they forfeit such a compensation as a charity. If the victim belonged to people who are at war with you, though he was a believer, you shall atone by freeing a believing slave. If he belonged to people with whom you have signed a peace treaty, you shall pay the compensation in addition to freeing a believing slave. If you cannot find* a slave to free, you shall atone by fasting two consecutive months, in order to be redeemed by GOD. GOD is Knower, Most Wise.

5:95 – Hunting During Pilgrimage

[5:95] O you who believe, do not kill any game during pilgrimage. Anyone who kills any game on purpose, his fine shall be a number of livestock animals that is equivalent to the game animals he killed. The judgment shall be set by two equitable people among you. They shall make sure that the offerings reach the Ka’bah. Otherwise, he may expiate by feeding poor people, or by an equivalent fast to atone for his offense. GOD has pardoned past offenses. But if anyone returns to such an offense, GOD will avenge it. GOD is Almighty, Avenger.

2:178 – Prescribed Law of Retaliation (Qisās)

[2:178] O you who believe, equivalence is the law decreed for you when dealing with murder—the free for the free, the slave for the slave, the female for the female. If one is pardoned by the victim’s kin, an appreciative response is in order, and an equitable compensation shall be paid. This is an alleviation from your Lord and mercy. Anyone who transgresses beyond this incurs a painful retribution.

2:144 – The Qiblah

[2:144] We have seen you turning your face about the sky (searching for the right direction). We now assign a Qiblah that is pleasing to you. Henceforth, you shall turn your face towards the Sacred Masjid. Wherever you may be, all of you shall turn your faces towards it. Those who received the previous scripture know that this is the truth from their Lord. GOD is never unaware of anything they do.

For Al-Shāfiʿī, these verses (and others) collectively demonstrate that Islamic law accepts action based on probabilistic judgment when definitive certainty is unattainable. In his view, ijtihād is not only permissible, but necessary in cases where revelation is silent or where the exact application requires human evaluation (like the examples above: determining equivalence in blood money, assigning penalties for hunting, establishing Qiblah direction in uncertain conditions, etc). Extending this logic, Al-Shāfiʿī argues that accepting solitary hadith reports, even if they do not reach the level of certainty (yaqīn), is valid because they fall within the same category of zann-based knowledge that Islamic law routinely permits. Just as we do not require absolute certainty when evaluating testimony or making legal analogies, we should not require certainty in every hadith report as long as integrity is applied to assess them.

Refutation of Al-Shāfiʿī’s Argument for Accepting Solitary Hadith (Khabar al-Āḥād)

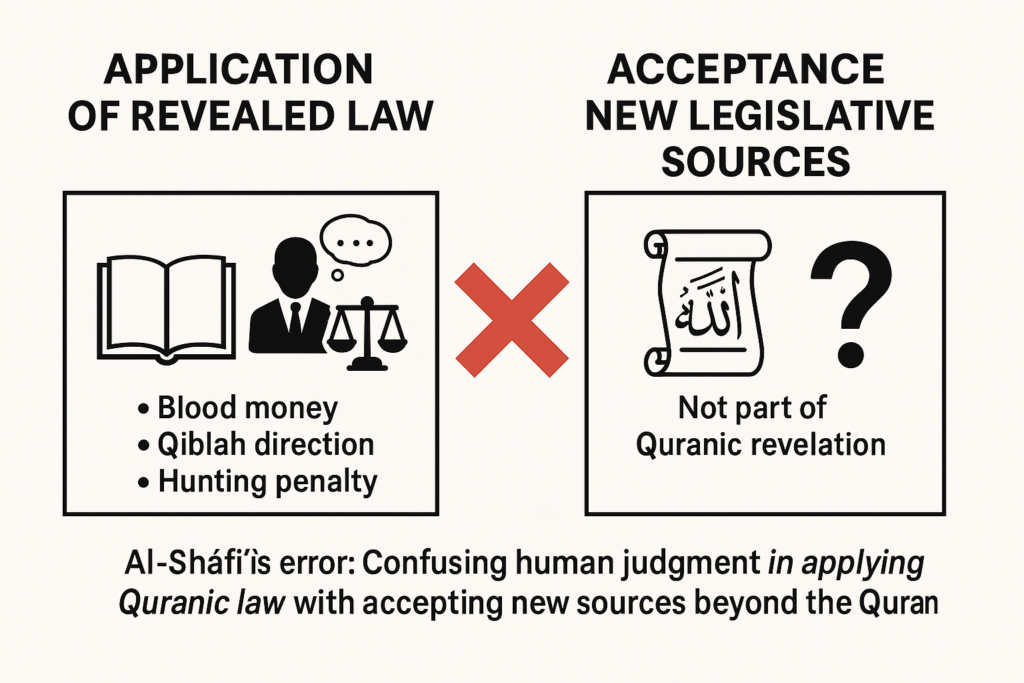

Al-Shāfiʿī commits a fundamental false analogy by equating Quranic commands that require human judgment in application with accepting extra-Quranic sources. These are categorically different. The verses he cites (blood money, hunting penalties, qisas, Qiblah) are all divine revelations requiring human judgment in their implementation. Hadith acceptance involves adding new sources of law beyond what God revealed.

Applying Quranic law with ijtihād ≠ accepting additional sources of law

His argument assumes what it’s trying to prove. He argues that since Islamic law (which he defines as including hadith) permits probabilistic knowledge, therefore, hadith should be accepted. But this presupposes that “Islamic law” rightfully includes hadith in the first place – the very point in contention. He even misrepresents many of the examples he cites:

Verse 4:92 (Accidental killing): This requires estimating equivalent compensation within Quranic parameters – not accepting new sources of law.

Verse 5:95 (Hunting during pilgrimage): Requires determining equivalent livestock – again, application of revealed law, not new legislation.

Verse 2:178 (Qisas): Establishes the principle of equivalence – the “probabilistic” element is in determining equivalent compensation within the Quranic framework.

Verse 2:144 (Qiblah): This actually undermines his argument! God directly revealed the Qiblah direction. When facing uncertainty about direction, believers use their best judgment to face the divinely specified direction, not accept alternative directions from other sources.

There is a fundamental confusion between two distinct epistemological domains in al-Shāfiʿī’s reasoning. Al-Shāfiʿī discusses the practical uncertainty involved in applying a revealed legal ruling, for example, estimating the amount of compensation equivalent to blood money or determining the direction of the Qiblah. He then equates this with the uncertainty regarding whether we should accept solitary hadith reports as authoritative sources for new divine legislation. However, these are entirely different types of judgments.

- The first is a human judgment exercised within the divinely established framework of the Quran. For instance, when a judge estimates the equivalent blood compensation in verse 4:92, he is applying Quranic law using human reasoning and ijtihād, but always within clear Quranic boundaries.

- The second is a judgment about accepting new sources of legislative authority beyond the Quran, effectively introducing external material into the religion. When scholars accept and select hadith reports as sources of law, they are elevating these reports to a status equivalent to revelation, which the Quran does not sanction.

Al-Shāfiʿī’s analogy, therefore, confuses uncertainty in the application of established divine rulings with uncertainty in the acceptance of new legislative sources, making the comparison invalid.

The Quran also explicitly warns against adding to or subtracting from God’s revelation:

- “These are God’s revelations that we recite to you truthfully. In which hadith, after God and His revelations, do they believe?” (45:6)

- “Shall I seek other than God as a source of law, when He has revealed to you this book fully detailed?” (6:114)

- “We did not leave anything out of the book” (6:38)

If probabilistic knowledge justifies accepting hadith, why stop there? By his logic, any “probable” religious claim from any source should be acceptable, which would open the door to infinite permutations of religious innovations. He claims rejecting hadith would make “Islamic legal reasoning impossible,” but Quran Alone adherents don’t reject reasoning – they reject additional sources beyond the Quran. The Quran itself provides comprehensive guidance and explicitly claims to be complete and detailed.

In summary, Al-Shāfiʿī presents a false dilemma:

- Either accept the hadith or

- Abandon all probabilistic reasoning (including the Quranic examples above)

Submitters engage in ijtihād within the Quranic framework without needing external sources. The fundamental flaw is treating the application of divine law (which requires human judgment) as equivalent to acceptance of additional sources of law (which contradicts Quranic sufficiency).