البخاري:٣١٧٥ – حَدَّثَنِي مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْمُثَنَّى حَدَّثَنَا يَحْيَى حَدَّثَنَا هِشَامٌ قَالَ حَدَّثَنِي أَبِي عَنْ عَائِشَةَ

أَنَّ النَّبِيَّ ﷺ سُحِرَ حَتَّى كَانَ يُخَيَّلُ إِلَيْهِ أَنَّهُ صَنَعَ شَيْئًا وَلَمْ يَصْنَعْهُ – صحيح (البخاري)

Translation:

Muḥammad b. al-Muthanná > Yaḥyá > Hishām from my father > ʿĀʾishah

Once the Prophet ﷺ was bewitched so that he began to imagine that he had done a thing which in fact he had not done. – Sound (Bukhārī)

bukhari:3175

The hadith narrating that the Prophet Muhammad was bewitched by a Jewish man is fraught with theological and textual issues that render it baseless when juxtaposed with the Quran. The Quran is unequivocal in affirming the Prophet’s mental clarity and divine protection from such afflictions. For instance, God reassures the Prophet in 68:2 –

[Quran – 68:2] You have attained a great blessing from your Lord; you are not crazy.

[Quran – 52:29] You shall remind the people. With your Lord’s blessings upon you, you are neither a soothsayer, nor crazy.

[Quran – 25:8] Or, “If only a treasure could be given to him!” Or, “If only he could possess an orchard from which he eats!” The transgressors also said, “You are following a bewitched man.”

Quran

Furthermore, Surah Al-Furqan (25:8) records the accusations of the transgressors who mockingly claimed, “You are following a bewitched man,” an allegation that the Quran itself refutes by presenting the Prophet’s impeccable character and mission as evidence of his truthfulness. These verses not only highlight the baselessness of the claim but also emphasize God’s safeguarding of the Prophet’s mission. Despite this clear Quranic testimony, the hadith in question persists in certain narrations, originating from Hisham ibn ‘Urwa, a controversial figure whose reliability has been challenged by numerous scholars. To fully expose the fabrications attributed to him, it is essential to examine both the origins and intent of this report.

Assessing the Isnads

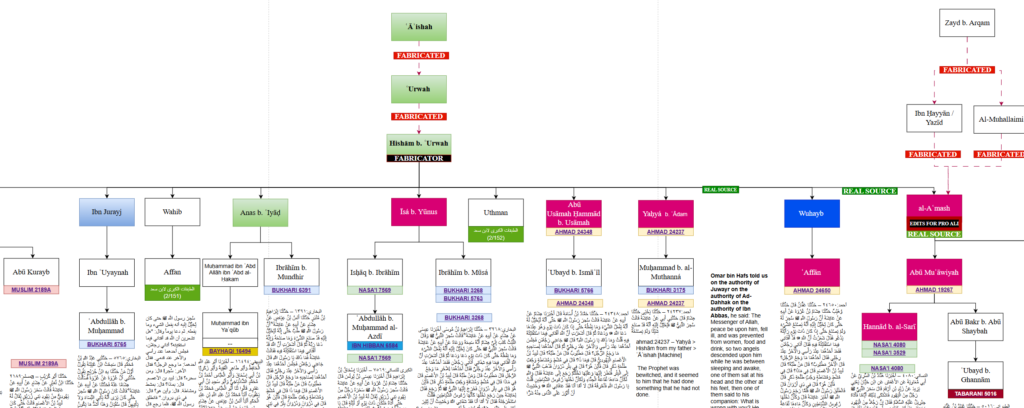

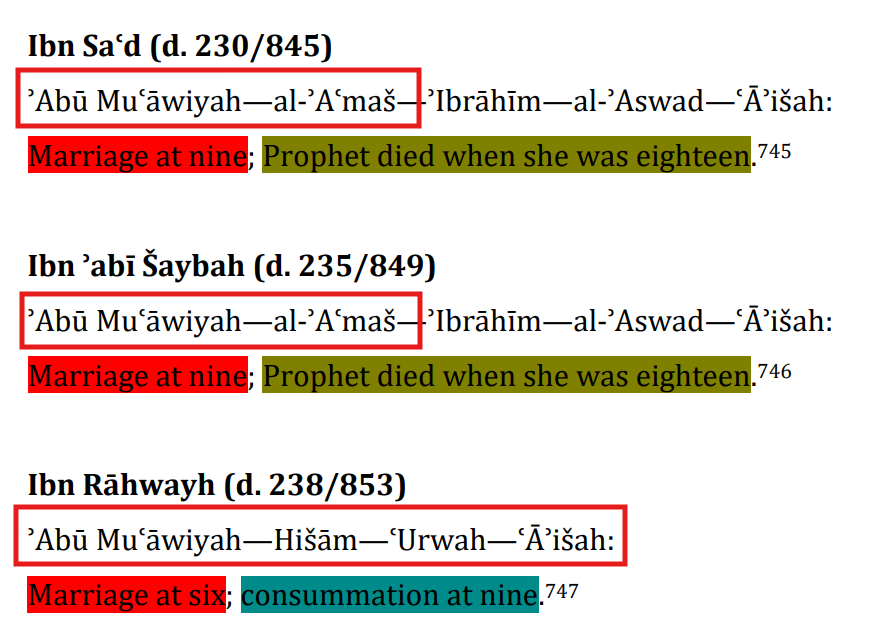

The different isnāds of the hadith about the Prophet being affected by magic all trace back to a single common link: Hisham ibn Urwa. Despite variations in transmitters and collections, Hisham consistently narrates this report from his father, Urwa ibn al-Zubayr, who attributes it to Aisha. This pattern is clear in the isnāds found in major hadith collections, including those of Ibn Hibban, Ahmad, Muslim, Bukhari, and Bayhaqi. Whether the chain involves Ibn Numayr, Anas ibn Iyad, or others, Hisham remains the key figure connecting the transmitters to the original source. This convergence highlights Hisham’s central role in transmitting this report, making him the primary link through which the narrative of the Prophet being affected by magic was preserved and shared across different compilations.

The three narrations in Musnad Ahmad (24237, 24348, and 24300) represent our earliest attestations of the hadith about the Prophet being affected by magic. These narrations are transmitted directly from Hisham ibn Urwa by three different transmitters: two Kufans (Yahya and Ibn Numayr) and one Medinan (Hammad ibn Usama). Their provenance provides insight into the early spread of this report through both Kufan and Medinan networks of hadith transmission. Below is a comparison table highlighting the key differences among these narrations.

| Narration | Arabic Matn | English Translation | Differences/Omissions/Additions | Context/Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad 24237 (Yahya) | حَدَّثَنَا يَحْيَى حَدَّثَنَا هِشَامٌ قَالَ حَدَّثَنِي أَبِي عَنْ عَائِشَةَ قَالَتْ سُحِرَ النَّبِيُّ ﷺ فَيُخَيَّلُ إِلَيْهِ أَنَّهُ قَدْ صَنَعَ شَيْئًا وَلَمْ يَصْنَعْهُ | Yahya narrated to us, Hisham narrated, he said: My father narrated to me from Aisha, who said: “The Prophet ﷺ was bewitched, and it was imagined to him that he had done something when he had not done it.” | This narration is concise and does not include the extended story about the two men or the discovery of the magical materials in the well. | Shortest of the three narrations, reflecting an early concise form of the report. |

| Ahmad 24348 (Hammad ibn Usama) | حَدَّثَنَا حَمَّادُ بْنُ أُسَامَةَ قَالَ أَخْبَرَنَا هِشَامٌ عَنْ أَبِيهِ عَنْ عَائِشَةَ قَالَتْ سُحِرَ رَسُولُ اللهِ ﷺ حَتَّى أَنَّهُ لَيُخَيَّلُ لَهُ أَنَّهُ يَفْعَلُ الشَّيْءَ وَمَا يَفْعَلُهُ… [Full narration provided earlier] | Hammad ibn Usama narrated to us, Hisham narrated from his father from Aisha, who said: “The Messenger of Allah ﷺ was bewitched to the extent that it was imagined to him that he was doing something when he was not doing it… (extended narrative follows).” | Adds an elaborate narrative, including the two men, their conversation, the identification of Labid ibn al-A’sam, the location of the well, the Prophet’s visit to it, and the description of the water and palm trees. | Provides a detailed account, showing progression and embellishment compared to 24237. |

| Ahmad 24300 (Ibn Numayr) | حَدَّثَنَا ابْنُ نُمَيْرٍ حَدَّثَنَا هِشَامٌ عَنْ أَبِيهِ عَنْ عَائِشَةَ قَالَتْ سَحَرَ رَسُولَ اللهِ ﷺ يَهُودِيٌّ مِنْ يَهُودِ بَنِي زُرَيْقٍ يُقَالُ لَهُ لَبِيدُ بْنُ الْأَعْصَمِ… [Full narration provided earlier] | Ibn Numayr narrated to us, Hisham narrated from his father from Aisha, who said: “A Jew from the Jews of Banu Zurayq, named Labid ibn al-A’sam, bewitched the Messenger of Allah ﷺ… (extended narrative follows).” | Similar to 24348 but includes slight variations in wording (e.g., specifying Labid as “a Jew from Banu Zurayq”). Adds final detail about the well being buried on the Prophet’s orders. | minor linguistic differences and additional details compared to 24348. |

The hadith about the Prophet being affected by magic appears to have originated from Hisham ibn Urwa, as evidenced by the isnāds in these hadith collections. This conclusion is supported by the fact that all known versions of the report ultimately trace back to Hisham as the pivotal transmitter. At least seven individuals transmitted this hadith from Hisham. Despite the variations in the chains of transmission and minor differences in wording, the core narrative remains consistent.

The convergence of isnāds on Hisham raises significant questions about the authenticity of the report, as it lacks corroboration from other independent sources beyond Hisham’s circle. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Hisham’s credibility as a transmitter was scrutinized by some scholars, particularly regarding the reports he narrated after moving to Iraq. Critics such as Malik ibn Anas and others have suggested that Hisham’s memory may have deteriorated in his later years, leading to doubts about the reliability of his transmissions during that period.

| Critic | Criticism | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Malik ibn Anas | Did not approve of Hisham, especially his narrations for the people of Iraq. Criticized him for changing the way he narrated reports over his three visits to Kufa. | Tahdhib al-Tahdhib (4/275) |

| Ya’qub ibn Shaybah | Reliable and trustworthy, but after moving to Iraq, he expanded his narrations from his father, which was denounced by the people of his region. His leniency was in transmitting from his father reports he had heard from others about his father. | Tahdhib al-Tahdhib (4/275) |

| Ibn Kharrash | Stated that Malik did not approve of Hisham’s narrations for the people of Iraq. Highlighted changes in Hisham’s transmission style over his three visits to Kufa, evolving from “my father told me” to “from my father, from Aisha.” | Tahdhib al-Tahdhib (4/275) |

| Malik ibn Anas (expanded) | Criticized him specifically for narrating to the Iraqis in ways that were not consistent with his usual standards when in Medina. | Tahdhib al-Tahdhib (4/275)* |

Given the absence of corroboration from other Medinan authorities or contemporaries of Urwa ibn al-Zubayr, it is plausible to consider that the report was either misrepresented or fabricated by Hisham. This hypothesis gains traction when analyzing the role of Hisham as the sole common link in the isnāds and the contextual factors that may have influenced his transmission. Further analysis of Hisham’s possible intent and the sociopolitical context in which the report emerged can shed light on why this narrative might have been constructed.

Al-A’mash/The Kufan Strand

We have 4 alternative accounts of the Hisham ibn Urwa hadith that does not go through Hisham ibn Urwa, but rather have Kufan tradents. The narrations from al-Tabarani, al-Nasa’i, and Ahmad present a version of the incident of the Prophet being affected by magic that diverges notably from the accounts commonly associated with Hisham ibn Urwa. These reports are transmitted through a different chain, beginning with Abu Muawiyah narrating from Al-A’mash, from Yazid ibn Hayyan, and ultimately from the Companion Zayd ibn Arqam. This chain is entirely distinct from the often-cited isnāds involving Hisham ibn Urwa, suggesting an independent line of transmission.

Here’s a comparison table for the hadiths narrated by Abu Muawiyah and the early Hisham ibn Uwa version found in Ahmad 24300:

| Hadith Source | Text | Omissions/Changes/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ahmad 24300 | حَدَّثَنَا ابْنُ نُمَيْرٍ حَدَّثَنَا هِشَامٌ عَنْ أَبِيهِ عَنْ عَائِشَةَ قَالَتْ سَحَرَ رَسُولَ اللهِ ﷺ يَهُودِيٌّ مِنْ يَهُودِ بَنِي زُرَيْقٍ يُقَالُ لَهُ لَبِيدُ بْنُ الْأَعْصَمِ حَتَّى كَانَ رَسُولُ اللهِ ﷺ يُخَيَّلُ إِلَيْهِ أَنْ يَفْعَلَ الشَّيْءَ وَمَا يَفْعَلُهُ…فَأَمَرَ بِهَا فَدُفِنَتْ | Detailed account of the Prophet being affected by magic, including the identity of the Jewish man, the supernatural visions experienced by the Prophet, the location of the magic (in a well), and the instructions to bury the magical object. Also includes Prophet’s reluctance to publicize the source of his affliction. |

| Abu Muawiyah (Tabarani 5016) | حَدَّثَنَا عُبَيْدُ بْنُ غَنَّامٍ ثنا أَبُو بَكْرِ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ ثنا أَبُو مُعَاوِيَةَ عَنِ الْأَعْمَشِ عَنْ يَزِيدِ بْنِ حَيَّانَ عَنْ زَيْدِ بْنِ أَرْقَمَ قَالَ سَحَرَ النَّبِيَّ ﷺ رَجُلٌ مِنَ الْيَهُودِ فَاشْتَكَى لِذَلِكَ أَيَّامًا فَأَتَاهُ جِبْرِيلُ ﷺ فَقَالَ إِنَّ رَجُلًا مِنَ الْيَهُودِ سَحَرَكَ… | Brief version of the story, stating the Prophet was affected by magic, but without specific mention of the name of the magician or the location of the magic. The healing process is more focused on the effect of the untying of knots. No mention of the Prophet’s internal visions or the magical object being buried. Gabriel & Ali are mentioned as being apart of helping the prophet which is mentioned nowhere else but these Abu Muawiyah variants. |

| Abu Muawiyah (Nasa’i 4080) | أَخْبَرَنَا هَنَّادُ بْنُ السَّرِيِّ عَنْ أَبِي مُعَاوِيَةَ عَنِ الْأَعْمَشِ عَنْ يَزِيدِ بْنِ حَيَّانَ عَنْ زَيْدِ بْنِ أَرْقَمَ قَالَ سَحَرَ النَّبِيَّ ﷺ رَجُلٌ مِنْ الْيَهُودِ فَاشْتَكَى لِذَلِكَ أَيَّامًا فَأَتَاهُ جِبْرِيلُ عَلَيْهِ السَّلَامُ فَقَالَ إِنَّ رَجُلًا مِنَ الْيَهُودِ سَحَرَكَ عَقَدَ لَكَ عُقَدًا فِي بِئْرِ كَذَا وَكَذَا…فَمَا ذَكَرَ ذَلِكَ لِذَلِكَ الْيَهُودِيِّ وَلاَ رَآهُ فِي وَجْهِهِ قَطُّ | Similar to the Tabarani version, this one is also brief and lacks the detailed specifics of the magic ritual. It includes the Prophet being affected and the healing process, but omits specifics about the object used and the Prophet’s internal experiences. The Jewish magician’s name and the specific location are not mentioned. Gabriel & Ali are mentioned as being apart of helping the prophet which is mentioned nowhere else but these Abu Muawiyah variants. |

| Abu Muawiyah (Nasai Al-Kubra 3529) | Similar to the previous Nasa’i version in style and content. The magic is acknowledged, and Gabriel’s role is highlighted, but it lacks specific details regarding the type of magic, the object used, and the emotional and psychological impact on the Prophet. The incident is again recounted in a more concise manner without the lengthy narrative of the burial of the magical object. | This version omits details about the Prophet’s specific visions and the instructions to bury the object. The only focus is on the recovery process after Gabriel’s intervention, with less emphasis on the Prophet’s internal suffering or any details that could implicate the Jewish magician or the cause of the affliction in-depth. Gabriel & Ali are mentioned as being apart of helping the prophet which is mentioned nowhere else but these Abu Muawiyah variants. |

The content of these narrations is simpler and less detailed compared to the Hisham tradition. The reports describe a Jewish man casting magic on the Prophet, leading to days of illness. Gabriel informs the Prophet about the location of the magical knots, which are retrieved by Ali ibn Abi Talib and untied, resulting in the Prophet’s immediate recovery. The narrative focuses on the Prophet’s physical restoration, using the vivid imagery of being “released from a tether,” but does not delve into psychological effects such as imagining things that did not occur. Notably, these narrations emphasize the Prophet’s restraint; despite knowing the identity of the perpetrator, he neither confronted nor punished the individual. These narrations, preserved in collections like al-Tabarani, al-Nasa’i, and Ahmad, provide an alternative version of the hadith to the Hisham tradition. So if Hisham ibn Urwa is the Common Link and originator of his version, then what explains Al-A’mash/Abu Muawiyah’s version of events?

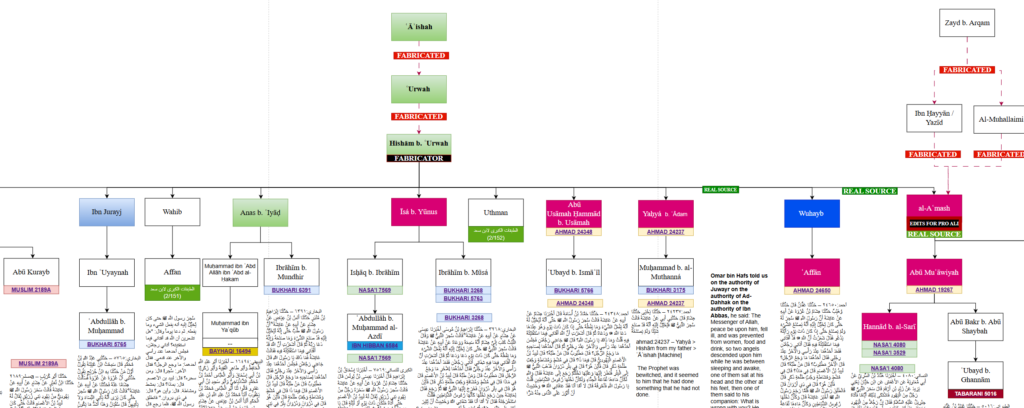

Dr. Joshua Little & The Marital Hadith of Aisha

2:11 – “Now what you will often also find, is that at least one other strand that bypasses a common link, and goes all the way back independently to the prophet, and so Schact thought that this was a false parallel pseudo corroborating isnad that was essentially the product of what he called, the spread of isnads, the spreading of isnads. So the idea is just that there are various incentives and pressures for people to create alternative paths of transmission, for materials that they liked. So it might be that people have there own preference of who should be in the isnad. For example there are regional preferences, there are familial or tribal preferences, there are sectarian preferences, additionally there is just the desire not to transmit from a contemporary – not to have uh you know if you met the person whom another person is citing I mean you you could just directly site that person as well even though you’re actually hearing it from a contemporary or you just might might want to shorter isnad so you construct an isnad with you know much longer lived people in it or for example you may just want a rare isnad or in general you might just want corroborating isnads because some early Muslims especially early rationalists demanded multiple independent isnads in order to accept hadiths. So there’s a whole regime of incentives and pressures that exist in the early period for people to create parallel independent seemingly independent isnads…”

Dr Joshua Little Excerpt Explaining Tradent Dives and ICMA – Clip from The Impactful Scholar on YT

Dr. Joshua Little explains the phenomenon of independent isnads, referring to chains of narration that appear to bypass a common link and go directly back to the Prophet. These independent chains can sometimes be seen as “false parallel pseudo-corroborating isnads,” which Schact believed were the result of what he called the “spread of isnads.” The idea behind this is that narrators or compilers may have created multiple chains of transmission for a single hadith to provide additional corroboration and make the hadith seem more authentic.

There were various pressures and incentives for doing this, including personal preferences for certain individuals to be included in the isnad, regional or sectarian biases, or simply the desire to have shorter isnads. Additionally, there was a demand among early Muslims, particularly rationalists, for multiple independent chains to ensure the reliability of a hadith. This process of constructing parallel isnads was a strategic move to enhance the credibility of a hadith by offering seemingly independent paths of transmission.

In the case of Al-A’mash, we can see how these principles apply. Al-A’mash’s isnad is a different account of the Jewish bewitching with a different strand of transmission that appears to provide corroboration for the same hadith. Motivations for constructing these parallel isnads could include a desire to make the hadith more credible, align with regional or tribal preferences, or simplify the chain by reducing the number of intermediaries.

Moreover, Al-A’mash’s sectarian views, particularly his affiliation with the Shia’s, might have influenced the creation of isnads that included narrators from his ideological circle. These independent chains were likely meant to bolster the authenticity of the hadith, especially when those narrations were of theological or doctrinal importance. The construction of independent isnads, as Dr. Little explains, was thus a strategic move in early Islamic scholarship to ensure that a hadith was supported by multiple sources and appeared more reliable, even when those chains might not have been as independent as they seemed.

Why Would Al-A’mash Cite Others If He Received It From Hisham ibn Urwa? Did He Ever Receive Hadith from Hisham?

Islamic Historical Memory

As Dr. Joshua Little demonstrated through his analysis of the marital hadith of Aisha, the concept of Hisham ibn Urwah fabricating hadith is not a new phenomenon. In line with his research, we find a Common Link where Hisham ibn Urwah claims to have received a hadith from his father, Urwah, who in turn claims to have received it from Aisha. Furthermore, we also have attestation from Al-A’mash who directly received transmission from Hisham. This establishes a reliable link between the two. Given this, it becomes plausible to consider the possibility that the hadith regarding the Jew who bewitched the Prophet Muhammad could have been an instance where Al-A’mash chose to cite his Kufan counterparts. Rather than openly acknowledging his true source, Hisham ibn Urwah, Al-A’mash concealed his true source.

Earlier, we mentioned Imam Malik ibn Anas, the leader of the Medinan Maliki school of thought, who raised concerns about Hisham ibn Urwah’s reliability. Let’s examine some of these criticisms:

Ibn Kharrash said: “Malik did not approve of him, though Hisham was truthful, and his reports are included in the authentic collections. I was informed that Malik criticized him for narrating to the people of Iraq. He went to Kufa three times: the first time, he would say, ‘My father told me, saying: I heard Aisha.’ The second time, he would say, ‘My father informed me from Aisha.’ The third time, he would say, ‘From my father, from Aisha.’ Among those who heard from him later were Waki’, Ibn Numayr, and Muhadir.” (Tahdhib al-Tahdhib 4/275)

Abd al-Rahman ibn Yusuf ibn Kharrash also said: “Malik did not approve of him, though Hisham was truthful, and his reports are included in the authentic collections. I was informed that Malik criticized him for narrating to the people of Iraq. He went to Kufa three times: the first time, he would say, ‘My father told me, saying: I heard Aisha.’ The second time, he would say, ‘My father informed me from Aisha.’ The third time, he would say, ‘From my father, from Aisha.’ Among those who heard from him later were Waki’, Ibn Numayr, and Muhadir.” (Tahdhib al-Kamal 30/232)

Tahdhib al-Tahdhib 4/275, Tahdhib al-Kamal 30/232

These critiques indicate that while Hisham ibn Urwah was generally seen as trustworthy in Medina, Imam Malik, a central figure in Medinan jurisprudence, harbored doubts about Hisham’s narrations. Malik’s disapproval stems not from Hisham’s truthfulness, but from his pattern of narrating to the people of Iraq, a practice Malik found problematic. Furthermore, Ibn Kharrash documents that Hisham visited Kufa multiple times, and it was during these visits that his narrations began to take on a different tone. Hisham’s increasing reliance on vague attributions like “My father told me” rather than providing direct, transparent chains raised red flags for scholars like Malik.

Dr. Little further explores this concern in his analysis of the marital hadith of Aisha. In particular, he noted that none of the hadiths discussing Aisha’s marriage at the age of six or nine appear in early Medinan legal works. This is significant because such narrations would have been vital content for early legal and juristic discussions, yet they were conspicuously absent. The explanation for this absence, Dr. Little suggests, is simple: the narrations did not exist at that time. They only emerged after Hisham ibn Urwah had relocated to Iraq, where the fabrication could be more easily incorporated into the region’s political and sectarian debates.

Dr. Little’s conclusion that the marital-age hadiths trace directly back to Hisham ibn Urwah’s time in Iraq is compelling. He explains:

“None of the hadiths can be traced back to Medina in the 7th or 8th centuries CE; they cannot be traced to earlier generations in Iraq either. All versions of the hadith trace back to an ur-version, with Hisham’s version being the most widespread. The unique qualities of Hisham’s version align with the characteristics of the ur-version, suggesting that Hisham himself played a central role in creating this hadith.“

Dr. Little argues that Hisham’s creation of the marital-age hadith aligns perfectly with his contextual motivations. The 8th-century ideological conflict between early proto-Sunnis and proto-Shi’is was intensifying, and Aisha was a central figure in these sectarian debates. The fabrication of a hadith extolling her virtues, including her status as the Prophet’s only virgin wife, would serve as an ideological defense for proto-Sunnis. Hisham, as a member of this group and a relative of Aisha, had a clear motivation for fabricating such a hadith, especially once he had settled in Kufa, a Shi’i stronghold where his fabricated version would gain traction among Sunnis.

Dating of The Bewitching: Pre-Move to Kufa, or Post-Move to Kufa?

Now that we’ve established the context and implications of the marital hadith of Aisha, let’s return to our focus on the hadith about the bewitching of the Prophet Muhammad. The marital hadith represents a pro-Aisha, pro-Sunni narrative crafted in response to an anti-Aisha, anti-Sunni context in Kufa. This fabricated narrative served a sectarian purpose by positioning Aisha as a symbol of Sunni virtue in the face of Shi’i opposition. On the other hand, the hadith of the bewitching, when considered within its context, makes far more sense within Medina than it does after Hisham ibn Urwah’s move to Kufa.

The bewitching hadith, which claims that a Jew bewitched the Prophet, presents a clear polemic that serves to undermine Jews while emphasizing the Prophet’s divine protection. This claim — that a Prophet of Islam could be subjected to such an indignity — would have been wholly incongruous with the image of the Prophet maintained by Kufa’s Shi’i-dominated intellectual environment. The Jews were often viewed with suspicion and hostility in Medina, where Jewish tribes such as Banu Harith, Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Shtayba, Banu Ghassan, and Banu Qurayza coexisted with the believers. In this environment, creating an anti-Jewish polemic made perfect sense. The Medinan context was rife with tension between Muslims and Jewish tribes, making the claim of a Jewish bewitching a strategic narrative to solidify the Prophet’s status as divinely protected and favored by God.

In contrast, Kufa, where Hisham ibn Urwah later settled, was a more Shi’i-leaning region. The notion of a Jew bewitching the Prophet would not carry the same weight or urgency there. Shi’ism, with its focus on the purity and divinity of the Prophet’s family, would not have had the same ideological need to elevate the Prophet’s protection from a Jewish adversary. Therefore, the bewitching hadith makes far more sense as a Medinan creation, aimed at reinforcing the Prophet’s might and divine favor in a context where Jewish communities posed a significant challenge to Muslim rule.

So how did Al-A’mash come to transmit this hadith from Hisham ibn Urwah? When we compare the transmission of this hadith by Al-A’mash to other reports from Hisham, subtle but notable differences emerge. These differences point to Al-A’mash’s possible modification or selective transmission of Hisham’s narration. By deliberately omitting his source, Al-A’mash could have recontextualized the hadith to better align with his own objectives or his audience’s expectations, rather than faithfully transmitting Hisham’s words in their original form:

—

Ahmad: 24300 – Ibn Numayr – Hisham ibn Urwa

“A Jewish man from the Banu Zurayq, named Labid ibn al-A’sam, bewitched the Messenger of Allah ﷺ. So much so that the Messenger of Allah ﷺ would imagine that he had done something, but he had not. A day or night came when the Messenger of Allah ﷺ called me, and then he called again, and said: ‘O Aisha, I feel that Allah has answered my request regarding what I sought His judgment on. Two men came to me and one sat at my head and the other at my feet. The one by my head said to the one by my feet, “What is wrong with the man?” He replied, “He is bewitched.” “Who has bewitched him?” “Labid ibn al-A’sam.” “What did he use?” “A comb and some hair, and the pollen of a male date palm.” “Where is it?” “In the well of Arwan.”‘ Aisha said: ‘The Messenger of Allah ﷺ went to the well with some of his companions, then came back and said: “O Aisha, the water looks like the liquid of henna, and its date palms look like the heads of devils.” I asked: “O Messenger of Allah, why didn’t you burn it?” He replied: “I have been healed by Allah, and I did not want to stir up evil among the people.” Then he ordered it to be buried.'”

In the Kufan/Al-A’mash version, Gabriel and Ali are cited to have helped the prophet when he was bewitched. Gabriel assisted the prophet by informing him of the bewitching, and Ali was the one who was sent by the Prophet to find the source of the magic. This adds significant Shi’i color to the hadith, emphasizing Ali’s direct involvement in the healing of the Prophet. It makes sense that Al-A’mash would include these figures—Gabriel and Ali—as the active agents, as this aligns with a pro-Shi’i sentiment that elevates Ali’s role and stature, particularly in situations of aiding and protecting the Prophet. This emphasis on Ali’s participation also strengthens his position as the divinely chosen figure capable of aiding the Prophet, reinforcing Shi’i views.

However, this narrative divergence becomes apparent when comparing it with Hisham ibn Urwa’s version, where no specific companion is mentioned in relation to the Prophet’s healing. Instead, the hadith focuses solely on the Prophet’s experience and divine intervention, not having any overt Shi’i embellishments. The insertion of Ali as a key figure in the Al-A’mash version seems to reflect a deliberate alteration to cater to a particular ideological stance, highlighting the Shi’i notion of Ali’s importance and proximity to the Prophet. This shift underscores the potential for Hadiths to be modified, whether through intentional or inadvertent transmissions, to reflect sectarian loyalties or political climates at the time of narration.

What Really Happened (pre-Kufan Fabrication)

The most plausible transmission history of this hadith would unfold as follows: Hisham ibn Urwah, living in Medina, was regarded by Imam Malik as generally trustworthy but marked with suspicion due to his frequent attribution of hadiths to his father (in addition to other criticisms, as mentioned earlier). Medina, at the time, was home to a number of Jewish tribes, and there was ongoing polemical debate about the validity of Prophet Muhammad’s prophethood a century after his death. In this environment, Hisham, motivated by the ideological and sectarian struggles of the time, sought to strengthen the position of the Prophet and assert his divine protection.

To this end, Hisham fabricated a hadith attributed to his father, Urwah, and his aunt, Aisha, recounting a false story in which a Jewish man bewitched the Prophet. This narrative not only sought to demonstrate the Prophet’s divine protection but also served as an anti-Jewish polemic. The hadith, emphasizing the Prophet’s supernatural healing and his protected status as a messenger, spread throughout Medina. However, it was not collected by Imam Malik because, being a non-legal or non-judicial hadith, it did not have a place in Malik’s legal compilations.

After leaving Medina for Kufa, Hisham continued to spread fabricated hadiths, including the marital-age Aisha hadith, as Dr. Little has pointed out, to counter Shi’i claims and reinforce Sunni positions. Hisham now presented the bewitching hadith to Al-A’mash, who further altered the text to fit the traditions of Kufa. In this version, Hisham attributed the narration to a false isnad through a recognized source in Kufa. This alteration provided a better sounding story with Ali being involved, which was later canonized in the collections of hadith.

Thus, we see a clear pattern of manipulation of transmission by Hisham, first fabricating the story in Medina to support the Prophet’s divine protection against Jewish hostility, then modifying the narration further in Kufa to gain acceptance within the Kufi tradition. This false corroboration of the isnad, over time, gained legitimacy and was included in later collections, solidifying its place in hadith literature despite its dubious origins.

The Preliminary assessment of this narration on X: https://x.com/HadithCritic/status/1758711719742869716

Pingback: Hisham ibn Urwa: The Man Who Stopped Menstruating Women From Praying - HadithCritic

Pingback: Isnad Politics: The Case of Al-A'mash and Hisham - HadithCritic