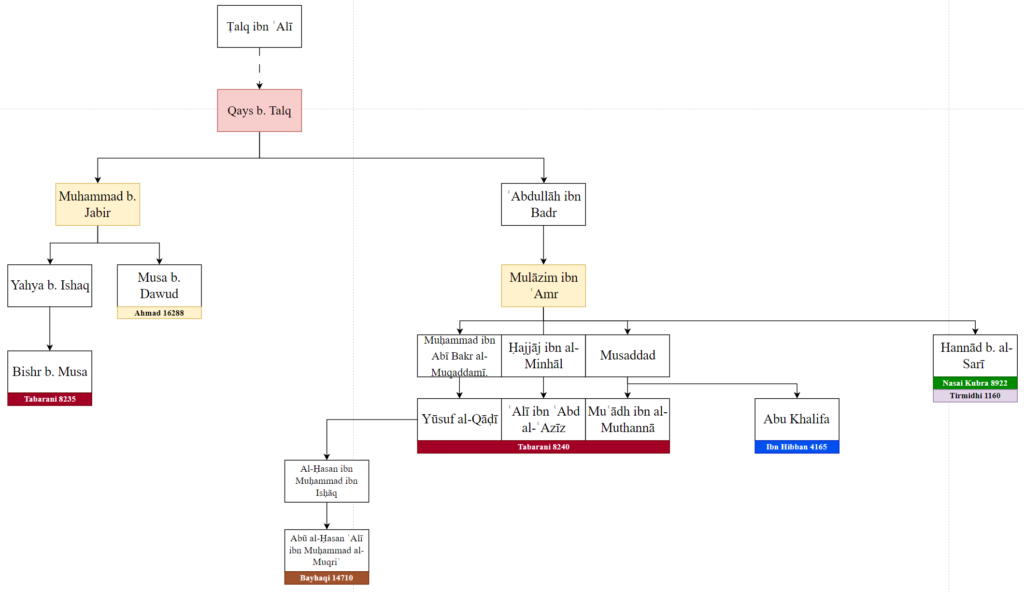

Throughout the history of hadith transmission, there have been instances where certain narrators have justified using the hadith corpus to enforce practices that were never commanded by the Prophet. In some cases, these narrators sought to manipulate religious texts to legitimize practices that aligned with their personal or societal agendas. One such example is the narration involving Qays ibn Talq, who serves as the common link in a tradition that states women are obligated to answer every sexual call of their husbands, regardless of the circumstances. This hadith, transmitted through various chains, serves as a tool to compel women to adhere to a specific behavior that were not authorized by the Prophet. By creating a false chain of transmission, these hadiths were propagated to force a particular social norm. Let’s take a closer look at this specific narration (and its variant traditions) and examine its authenticity, context, and the implications.

| Source | Isnad | Arabic Text (Matn) | English Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

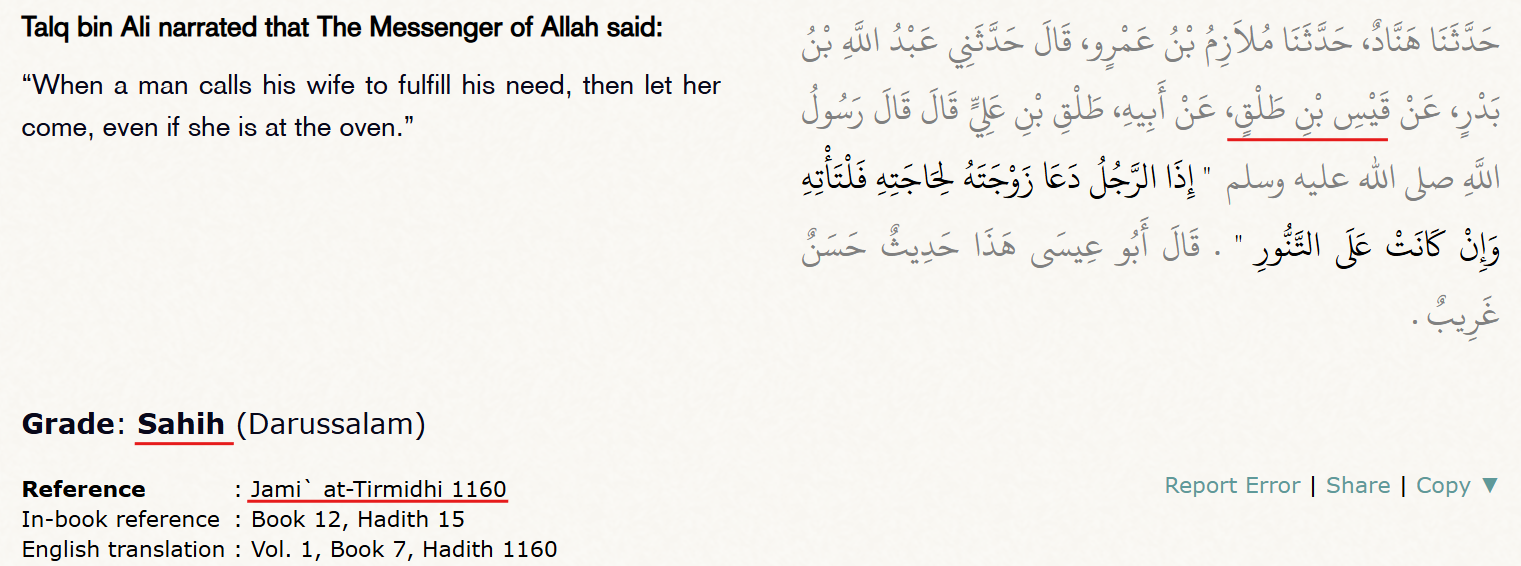

| Al-Nasa’i (Al-Kubra, 8922) | Hannad ibn Al-Sari → Mulazim ibn Amr → Abdullah ibn Badr → Qays ibn Talq → Talq ibn Ali | إِذَا الرَّجُلُ دَعَا زَوْجَتَهُ لِحَاجَتِهِ فَلْتَأْتِهِ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ عَلَى التَّنُّورِ | “If a man calls his wife for his need, she should come to him, even if she is at the tannur (oven).” | Uses “دَعَا” (calls) and “فَلْتَأْتِهِ” (she should come to him). No explicit grading given. |

| Al-Tirmidhi (1160) | Hannad → Mulazim ibn Amr → Abdullah ibn Badr → Qays ibn Talq → Talq ibn Ali | إِذَا الرَّجُلُ دَعَا زَوْجَتَهُ لِحَاجَتِهِ فَلْتَأْتِهِ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ عَلَى التَّنُّورِ | “If a man calls his wife for his need, she should come to him, even if she is at the tannur (oven).” | Same wording as Al-Nasa’i. Graded as Hasan Gharib by Al-Tirmidhi. |

| Ibn Hibban (4165) | Abu Khalifa → Musaddad → Mulazim ibn Amr → Abdullah ibn Badr → Qays ibn Talq → Talq ibn Ali | إِذَا دَعَا الرَّجُلُ زَوْجَتَهُ لِحَاجَتِهِ فَلْتُجِبْهُ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ عَلَى التَّنُّورِ | “If a man calls his wife for his need, she should respond to him, even if she is at the tannur (oven).” | Replaces “فَلْتَأْتِهِ” with “فَلْتُجِبْهُ” (she should respond to him). Graded as Sahih. |

| Al-Tabarani (8240) | Ali ibn Abdul-Aziz → Hajjaj ibn Al-Minhil → Mulazim ibn Amr → Abdullah ibn Badr → Qays ibn Talq → Talq ibn Ali | إِذَا دَعَا الرَّجُلُ زَوْجَتَهُ لِحَاجَتِهِ فَلْتُجِبْهُ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ عَلَى التَّنُّورِ | “If a man calls his wife for his need, she should respond to him, even if she is at the tannur (oven).” | Matches Ibn Hibban. No explicit grading given. |

| Al-Bayhaqi (14710) | Abu Al-Hasan → Al-Hasan ibn Muhammad → Yusuf ibn Yaqub → Muhammad ibn Bakr → Mulazim ibn Amr → Abdullah ibn Badr → Qays ibn Talq → Talq ibn Ali | إِذَا الرَّجُلُ دَعَا زَوْجَتَهُ لِحَاجَتِهِ فَلْتُجِبْهُ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ عَلَى التَّنُّورِ | “If a man calls his wife for his need, she should respond to him, even if she is at the tannur (oven).” | Matches Ibn Hibban and Al-Tabarani in wording. No explicit grading given. |

| Ahmad (16288) | Musa ibn Dawud → Muhammad ibn Jabir → Qays ibn Talq → Talq ibn Ali | إِذَا أَرَادَ أَحَدُكُمْ مِنْ امْرَأَتِهِ حَاجَةً فَلْيَأْتِهَا وَلَوْ كَانَتْ عَلَى تَنُّورٍ | “If one of you wants something from his wife, let him go to her, even if she is at the tannur (oven).” | Uses “أَرَادَ” (wants) and “فَلْيَأْتِهَا” (let him go to her). Graded as Da’if. |

| Al-Tabarani (8235) | Bishr ibn Musa → Yahya ibn Ishaq → Muhammad ibn Jabir → Qays ibn Talq → Talq ibn Ali | إِذَا أَرَادَ أَحَدُكُمْ مِنَ امْرَأَتِهِ حَاجَتَهَا فَلْيَأْتِهَا وَلَوْ كَانَتْ عَلَى تَنُّورٍ | “If one of you wants something from his wife, let him go to her, even if she is at the tannur (oven).” | Matches Ahmad. No explicit grading given. |

Matn Differences:

- The phrase “فَلْتَأْتِهِ” vs. “فَلْتُجِبْهُ” appears to be the primary variation.

- Some versions use “إِذَا أَرَادَ” instead of “إِذَا دَعَا”.

Chain of Transmission:

- Most sources trace the isnad through Qays ibn Talq from his father Talq ibn Ali, with slight variations in intermediaries.

- The narrators Mulazim ibn Amr and Abdullah ibn Badr appear consistently.

Narrations Through Muhammad ibn Jabir

Ahmad (16288)

Arabic:

إِذَا أَرَادَ أَحَدُكُمْ مِنْ امْرَأَتِهِ حَاجَةً فَلْيَأْتِهَا وَلَوْ كَانَتْ عَلَى تَنُّورٍ

Translation:

“If one of you wants something from his wife, let him go to her, even if she is at the tannur (oven).”

Al-Tabarani (8235)

Arabic:

إِذَا أَرَادَ أَحَدُكُمْ مِنَ امْرَأَتِهِ حَاجَتَهَا فَلْيَأْتِهَا وَلَوْ كَانَتْ عَلَى تَنُّورٍ

Translation:

“If one of you wants something from his wife, let him go to her, even if she is at the tannur (oven).”

Narrations Through Mulazim ibn Amr

Al-Nasa’i (Al-Kubra, 8922)

Arabic:

إِذَا الرَّجُلُ دَعَا زَوْجَتَهُ لِحَاجَتِهِ فَلْتَأْتِهِ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ عَلَى التَّنُّورِ

Translation:

“If a man calls his wife for his need, she should come to him, even if she is at the tannur (oven).”

Al-Tirmidhi (1160)

Arabic:

إِذَا الرَّجُلُ دَعَا زَوْجَتَهُ لِحَاجَتِهِ فَلْتَأْتِهِ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ عَلَى التَّنُّورِ

Translation:

“If a man calls his wife for his need, she should come to him, even if she is at the tannur (oven).”

Ibn Hibban (4165)

Arabic:

إِذَا دَعَا الرَّجُلُ زَوْجَتَهُ لِحَاجَتِهِ فَلْتُجِبْهُ وَإِنْ كَانَتْ عَلَى التَّنُّورِ

Translation:

“If a man calls his wife for his need, she should respond to him, even if she is at the tannur (oven).”

Key Differences Between Chains:

- Focus of Action:

- Muhammad ibn Jabir narrations emphasize the husband’s role:

- “فَلْيَأْتِهَا” (let him go to her).

- Mulazim ibn Amr narrations emphasize the wife’s role:

- “فَلْتَأْتِهِ” (she should come to him) or “فَلْتُجِبْهُ” (she should respond to him).

- Muhammad ibn Jabir narrations emphasize the husband’s role:

- Initiation:

- Muhammad ibn Jabir narrations are initiated by the husband’s desire (أَرَادَ).

- Mulazim ibn Amr narrations are initiated by the husband’s call (دَعَا), reflecting a verbal request.

- Terminology:

- Muhammad ibn Jabir uses حَاجَةً (general need or desire).

- Mulazim ibn Amr uses حَاجَتِهِ (his need), specifying the husband’s request.

- Consistency:

- The Mulazim ibn Amr narrations are relatively consistent across sources (Al-Nasa’i, Al-Tirmidhi, Ibn Hibban, etc.).

- The Muhammad ibn Jabir narrations differ slightly in phrasing (Ahmad vs. Al-Tabarani).

Interpolation

It seems to be the case that Muhammad ibn Jabir received a similar hadith to that of Mulazim ibn Amr/Abdullah ibn Badr. The common link for this tradition would be Qays b. Talq

When consulting the ilm al rijal, we have mixed reviews on this narrator:

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | قَيْسُ بْنُ طَلْقِ بْنِ عَلِيِّ بْنِ الْمُنْذِرِ (Qays ibn Talq ibn Ali ibn al-Mundhir) |

| Lineage | حَنَفِي، يَمَامِيّ (Hanafi – Yamami) |

| Relations | ابن أخيه: عجيبة بن عبد الحميد, ابنه: هوذة بن قيس بن طلق الحنفي |

| Date of Death | 121 هـ – 130 هـ |

| Narrator Rank | الطبقة الثالثة |

| Rank by Ibn Hajar | صَدُوقُ |

| Rank by Al-Dhahabi | وثقه العجلي |

| Criticism and Praise | Ibn Hiban: Included in Al-Thiqaat, trusted by Al-‘Ajali. |

| – | Ibn Hajar: Classified in the third generation, famous Tabi’i, reliable. |

| – | Al-Daraqutni: Said not strong. |

| – | Al-Shafi’i: Did not find sufficient knowledge of him to accept his reports. |

| – | Al-‘Ajali: Considered him a reliable Tabi’i. |

| Al-‘Ajali | Known as trustworthy and classified as a Yemeni Tabi’i. |

| Al-Khallaal | Ahmad ibn Hanbal: Said others were more reliable than him. |

| Al-Mizzi | His father, Talq ibn Ali, was a companion of the Prophet (صلى الله عليه وسلم). |

| Al-Darimi | Said that Yahya ibn Ma’in considered his narrations as coming from trustworthy Yemeni elders. |

Not Looking Good For Qays

It’s plausible that Qays ibn Talq fabricated this hadith, attributing it to his father, in an effort to legitimize a practice by fabricating a chain of narration to the prophet. By creating a false chain of narration and linking it to his father, Qays was able to connect this tradition to the Prophet and present it as a legitimate narration. This manipulation allowed the narration to be passed along through various chains, reinforcing a narrative that would ultimately serve the agendas of those who sought to impose strict and potentially harmful expectations on women.

The Quran provides clear verses that contradict the ideas proposed in this fabricated hadith. For example, Surah An-Nisa (4:19) commands men to “treat them nicely” and emphasizes mutual respect and compassion within marriage.

[4:19] O you who believe, it is not lawful for you to inherit what the women leave behind, against their will. You shall not force them to give up anything you had given them, unless they commit a proven adultery. You shall treat them nicely. If you dislike them, you may dislike something wherein GOD has placed a lot of good.

Quran 4:19

Similarly, Surah Al-Baqarah (2:223) acknowledges the importance of consent and mutual desire in marital relations, stating,

[2:223] Your women are the bearers of your seed. Thus, you may enjoy this privilege however you like, so long as you maintain righteousness. You shall observe GOD, and know that you will meet Him. Give good news to the believers.

Quran 2:223

These verses emphasize equality, consent, and respect between spouses, fundamentally challenging the abusive nature of the hadith that mandates women to answer every call without consideration for their circumstances.

Moreover, the Quran warns against fabricating false statements in the name of the Prophet. Surah Al-An’am (6:112) explicitly states:

[6:112] We have permitted the enemies of every prophet—human and jinn devils—to inspire in each other fancy words, in order to deceive. Had your Lord willed, they would not have done it. You shall disregard them and their fabrications.

[6:113] This is to let the minds of those who do not believe in the Hereafter listen to such fabrications, and accept them, and thus expose their real convictions.*

Quran 6:112 – 113

This verse implies that enemies of the Prophet sought to create falsehoods and spread misleading teachings in order to distort the authentic message. It is not beyond possibility that such enemies of the Prophet, or those with personal agendas, might have fabricated sayings in order to promote ideas that were contrary to the true spirit of the religion.

The tradition regarding women’s compulsory submission to the sexual demand of their spouse is not only unsubstantiated by the Quran, but also abusive in nature. It undermines the principles of mutual respect, dignity, and kindness that the religion upholds in marital relationships. By allowing such fabrications to be passed as legitimate, they create a dangerous precedent that fosters inequality, disrespect, and abuse. It becomes very clear that individuals within the corpus of Hadith, like Qays, deceived large masses of individuals and scholars into believing such statements, defying 6:113, “…You shall disregard them and their fabrications.“

For more on hadith scholars inserting their whims and desires into the hadith corpus: