The hadith stating that “if a husband calls his wife to bed and she refuses, causing him to sleep in anger, the angels will curse her until morning” (Sahih al-Bukhari 3237) is often cited as a justification for women’s obligation to satisfy their husbands’ sexual demands. This narration has long been controversial, not only due to its ethical implications but also because of potential issues within its transmission. This article examines the authenticity and implications of this hadith, drawing on historical analysis of its transmission (isnad) and the cultural context in which it might have originated. By analyzing the hadith’s isnad, various chains of transmission, and possible biases, this analysis argues that the hadith is more likely a fabricated or unreliable narration rather than a divinely sanctioned teaching.

The Context and Content of the Hadith

The narration in question stems from various hadith collections, including Bukhari and Muslim, which are widely considered authentic. The crux of the hadith asserts a one-sided “obligation” on women to fulfill their husbands’ sexual demands or face divine punishment, which has sparked modern backlash, especially given its apparent misogynistic implications. Proponents of the hadith argue it reinforces marital harmony, while critics argue it promotes a double standard, objectifies women, and subjects them to unwarranted spiritual consequences.Analyzing the Transmission (Isnad) Chain

To determine the credibility of this hadith, a close examination of the transmission chain is essential. Scholars have pointed out issues with the authenticity of this narration, particularly through the intermediary transmitters:

- Primary Chain (Abu Huraira): The hadith is attributed to Abu Huraira, who is known for narrating a large number of hadiths. His reliability has been debated, particularly since his narrations often contradict those of other companions who lived closely with the Prophet.

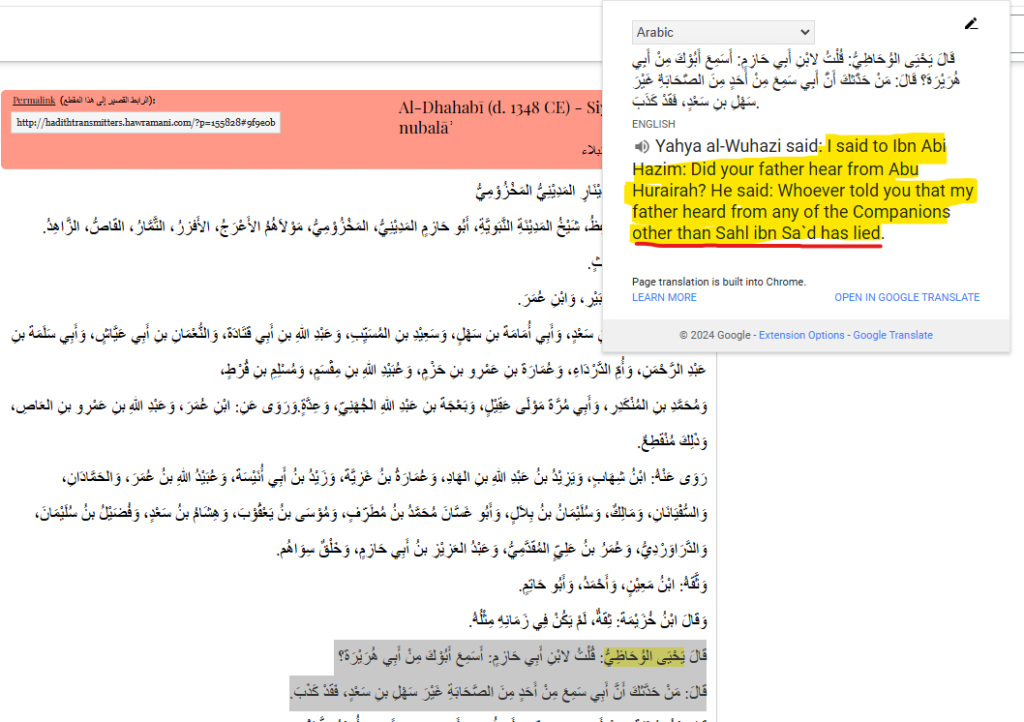

- Transmission to Abu Hazm: One critical issue arises in the connection between Abu Huraira and Abu Hazm. According to sources, Abu Hazm likely never met Abu Huraira directly, calling into question whether he could authentically relay narrations from him. The son of Abu Hazm is reported to have stated that his father never actually heard any hadith from a companion, except one (cited below). This statement directly challenges the veracity of Abu Hazm’s claim to have received this narration from Abu Huraira.

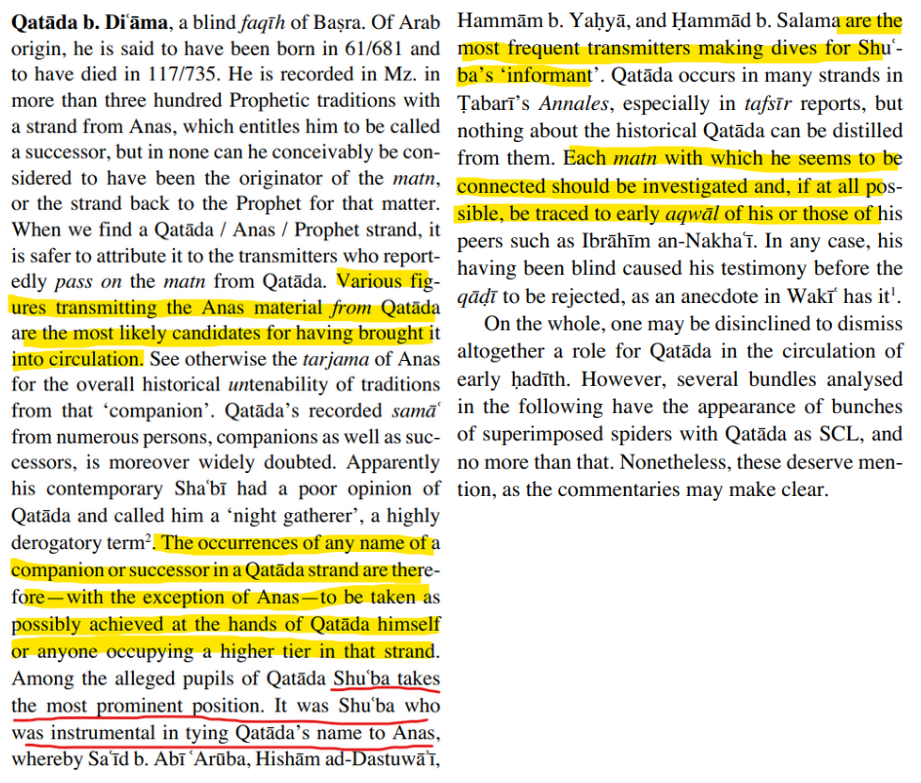

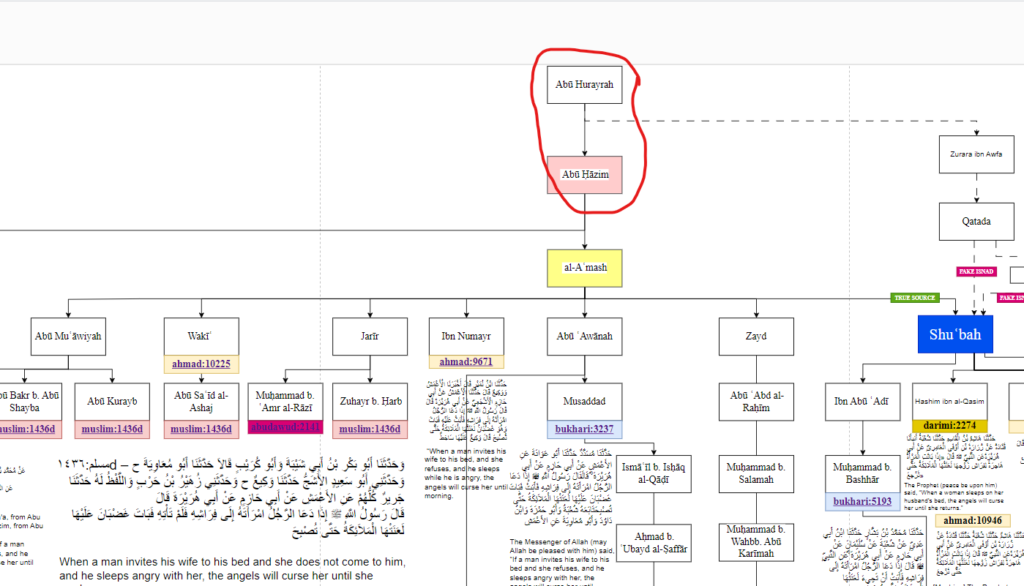

- Fabrication Indicators (Qatada and Shuba): Another issue involves the prominent Basran narrator, Qatada. Scholarly research, including in Juynboll’s “Encyclopedia of Hadith,” notes that Shuba, a student of Qatada, has been documented to manipulate isnads through Qatada to lend additional credibility to hadiths. This isnad manipulation is evident in numerous other narrations attributed to Qatada, particularly when narrators like Shuba inserted Abu Huraira’s name to create an illusion of authenticity.

Evidence of Fabrication: Role of Shuba and Qatada

Several strands of this hadith rely heavily on Qatada and Shuba’s influence. Shuba has been accused in some instances of adjusting isnads through Qatada to circumvent the need for other sources, effectively fabricating independent isnads back to the Prophet. This intentional adjustment appears to artificially elevate the status of Qatada’s narrations by attaching them to prominent figures like Abu Huraira. Since Shuba’s relationship with Qatada has been scrutinized for such practices, there is reason to suspect that this hadith may have been subject to similar manipulations. Juynboll’s study on the transmission techniques of Shuba underscores the extent to which isnad manipulation was used to legitimize hadiths. He explains that Shuba would fabricate independent isnads by attributing narrations to figures like Abu Huraira or Anas, even when his true source was another Basran transmitter. This process casts substantial doubt on the reliability of the isnad leading to Abu Huraira, a critical factor since this hadith heavily relies on such connections.

Divergence in Hadith Versions: Indications of Evolution

Another element that raises suspicion about this hadith’s authenticity is the existence of multiple, conflicting versions:

- Swearing by God’s Name: One version of the hadith attributes the words, “By Him in whose hand is my soul” to the Prophet, suggesting a more severe divine command. However, other versions omit this phrase, indicating possible later additions meant to bolster the hadith’s authority.

- Absence of Angelic Cursing: Some versions of the hadith merely state that God is “displeased” with the woman who refuses her husband’s invitation, whereas others emphasize an angelic curse. This inconsistency signals that the idea of “angels cursing” may be an interpolation that crept into the narration over time to amplify the gravity of a woman’s refusal.

Cultural Context and Patriarchal Bias

It is essential to examine the sociocultural context in which these narrations likely emerged. The Arabian Peninsula during the early Islamic period was heavily patriarchal, where women’s roles were largely confined to domestic spheres. This cultural backdrop may have influenced narrators to project societal expectations onto religious teachings. Thus, while the Qur’an emphasizes mutual respect and compassion within marriage (Quran 30:21), certain hadiths, like the one under examination, may reflect a patriarchal bias rather than divine intent. This hypothesis aligns with research by scholars like Fatima Mernissi, who argue that many narrations were influenced by societal norms and later inserted into hadith collections to reinforce male dominance.

Ethical and Theological Implications

Beyond questions of authenticity, this hadith also has problematic theological and ethical implications. It contradicts the Qur’anic principle of marital compassion and mutual consent. Imposing spiritual guilt or divine punishment on women who decline sexual relations introduces a form of coercion, which is fundamentally at odds with the Qur’anic call for kindness and fairness within marriage. Furthermore, no similar obligations are imposed upon men, which introduces a troubling double standard inconsistent with Quranic principles of justice and equity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the analysis of the hadith about “angels cursing women who do not comply with their husbands’ sexual requests” reveals significant concerns regarding its authenticity, transmission, and ethical implications. Upon examining the isnad (chain of transmission) and matn (content) through critical scholarly frameworks, it becomes evident that the hadith may not only suffer from fabrication but also bears marks of later social and cultural interpolations, possibly motivated by the reinforcement of specific patriarchal norms that favored male authority in domestic relationships. This assessment aligns with numerous criticisms raised by scholars who scrutinize narrations that conflict with fundamental Quranic principles or ethical justice.

Firstly, the dubious transmission chain — involving Abu Hazm, Qatada, and Shuba — raises considerable doubts about the hadith’s origin. Testimonies from scholars like Yahya al-Wazir and the statements attributed to Abu Hazm’s son assert that Abu Hazm never received narrations from Abu Huraira, casting suspicion over those claiming otherwise. Furthermore, variations in narration, as identified in sources like Bukhari, Sahih Muslim, and the Musnad of Ahmad ibn Hanbal, suggest that this hadith underwent significant alterations and embellishments, with later transmitters attempting to enhance its authority by tracing it back to respected figures like Abu Huraira. Such inconsistencies indicate a troubling pattern where, under scrutiny, the isnad collapses and no longer supports the narration’s purported legitimacy.

Moreover, the ethical ramifications of this hadith cannot be ignored. The hadith’s content appears to be fundamentally at odds with the Quran’s teachings on marital relationships, which emphasize compassion, mutual respect, and kindness between spouses (Quran 30:21). The Quran advocates for a marriage based on “love and mercy,” a concept that this hadith disrupts by assigning a coercive duty to women and threatening them with divine punishment for non-compliance. This narrative contradicts the Quran’s broader principles of personal agency, mutual consultation, and equity within marriage (Quran 2:187). It further risks perpetuating an imbalance of power, misrepresenting the ideals of Quranic ethics in a way that prioritizes male desires over female autonomy and moral dignity.

Additionally, the integration of fabricated or dubious narrations into canonical texts, despite ethical incongruities and weak chains of transmission, underscores a structural issue within hadith compilation methodologies of early scholars. These compilers often lacked the necessary contextual filters to evaluate hadiths against Quranic values fully. Consequently, problematic narrations like this one were preserved, allowing certain interpretations to solidify over time. The result has been a body of hadith literature that, while idolized, includes a corpus filled with shirk, misogyny, and anti-Quranic ideals mixed in with fabricated truths.

Pingback: Hadith Scholars Fulfilling Their Desires in Hadith - hadithcriticblog.com