Within traditionalist interpretations of Islamic law, it is commonly held that men are permitted to marry up to four wives, based on a reading of 4:3. At the same time, biographical and hadith literature reports that the Prophet Muhammad was married to nine or more women simultaneously. Does 4:3 establish a definitive upper limit on the number of wives a man may have? Is the verse context-specific, or is it intended as a general principle? And if a limit is indeed present, do the hadith-based reports of the Prophet’s marriages reflect an exception to this rule, or a contradiction?

The Quran repeatedly emphasizes that the Prophet Muhammad was not an independent legislator, but rather a conduit for divine revelation. He was bound to implement and follow the commands revealed to him without alteration. This principle is made explicit in 10:15, where Muhammad is instructed to reject any demand to modify the revelation:

[10:15] When our revelations are recited to them, those who do not expect to meet us say, “Bring a Quran± other than this, or change it!” Say, “I cannot possibly change it on my own. I simply follow what is revealed to me. I fear, if I disobey my Lord, the retribution of an awesome day.”

This verse firmly establishes that Muhammad was not permitted to deviate from the contents of the Quran. His role was to convey, follow, and embody the revelation (e.g., 6:114–115, 46:9). In light of this, any assessment of the Prophet’s conduct must begin with the Quran as the normative standard against which all actions (even those attributed to him in later sources) are measured.

This has direct implications for 4:3, a verse that lays out a specific condition under which polygamy is permitted:

[4:3] If you deem it best for the orphans, you may marry their mothers—you may marry two, three, or four. If you fear lest you become unfair, then you shall be content with only one, or with what you already have. Additionally, you are thus more likely to avoid financial hardship.

Traditional 4:3 Tafsirs

The tradition recognizes 4:3 to prohibit the number of wives a man can have to be 4.

Tafsīr Kitāb Allāh al-ʿAzīz by al-Hawwārī (3rd century AH)

In pre-Islamic times, a man would marry up to ten women or fewer. Then God made it lawful for him to marry up to four. He said:

{Then marry what pleases you from among the women},

{two, three, or four} — and if you fear that you will not be just with four, then marry three. If you fear you won’t be just with three, then marry two. If you fear injustice even with two,

then {marry one, or those your right hands possess} — meaning, you may have intercourse with what your right hand possesses (i.e., female slaves), however many you wish.

al-Bayḍāwī (Anwār al-Tanzīl wa-Asrār al-Taʾwīl, d. 685 AH)

{Two, three, or four (mathnā, wathulāth, warubāʿ)}

These terms are derived from repeated numbers: two-by-two, three-by-three, and four-by-four. They are indeclinable (not taking grammatical case endings) due to their structural modification (taʿdīl) and adjectival usage — they were formed as adjectives though their roots weren’t originally adjective forms. Some say this structure emphasizes repetition or multiplicity.

They are set in the accusative case (ḥāl, or circumstantial qualifier) related to the verb “marry” (ṭāba lakum). The meaning is: permission is granted to any man who desires polygamy to marry as many as he wishes of the stated numbers — whether the same number or different. Similar to saying: “Divide this wealth in twos, threes, or fours.”

If the numbers had been listed singly, the verse would have meant it is allowed to marry only one of each group. If “or” (aw) had been used instead of “and,” it would indicate mutual exclusivity in the numbers (i.e., you may only marry two or three or four, not any combination).

al-Tafsīr al-Kabīr by al-Ṭabarānī (d. 360 AH)

The Meaning of the Verse:

God’s statement: {If you fear that you will not be just with the orphans…} —

Ibn ʿAbbās said:When the verse {Indeed, those who consume the wealth of orphans unjustly…} [Qur’an 4:10] was revealed, people began to fear that they would not act justly in the property of orphans.

At the same time, they used to marry however many women they wanted.

So this verse was revealed to regulate both.Its meaning: If you fear you will not be just with orphans’ wealth, then also fear being unjust to women if you marry many of them.

So only marry as many women as you can properly care for.

This means: marry what is lawful for you, and do not marry more than you can sustain — two, three, or four.

Do not exceed four free women.

It’s pretty normative to see classical Sunni exegetes come out and say that the upper-bound limit of how many wives a man can have is 4. The difficulty arises not from the verse’s clarity, but from post-Quranic reports that attribute to the Prophet nine to eleven concurrent wives, which serves as a direct violation of the limit affirmed by both the Quran and the tafsirs. While some traditionalist scholars argue that the Prophet was exempted from the restriction based on 33:50, this exemption is not unambiguous, and 33:52 appears to impose a restriction, not an open-ended allowance. This discrepancy raises a central question:

How can the Prophet, who is expressly forbidden from deviating from revelation (10:15), be said to violate or be exempt from a legal limit clearly established in 4:3?

Enumerative vs. Definitive

At first glance, this appears to define a permissible range: “two, three, or four.” However, some have argued that this phrasing is descriptive, not prescriptive. The verse enumerates examples, not necessarily a fixed maximum. In Arabic, the phrasing uses a conjunction of numbers (مَثْنَىٰ وَثُلَاثَ وَرُبَاعَ), a construction that may reflect idiomatic variety more than a restrictive limit.

The most compelling evidence against numerical limitation comes from the direct linguistic parallel in Quran 35:1, which describes angels as having wings “مَثْنَىٰ وَثُلَاثَ وَرُبَاعَ” (mathna wa thulatha wa ruba’a) before explicitly stating “يَزِيدُ فِي الْخَلْقِ مَا يَشَاءُ” (yazidu fi’l-khalqi ma yasha’u – “He adds to creation as He wills”). This identical construction in 35:1 definitively proves that the Arabic pattern “mathna wa thulatha wa ruba’a” serves as exemplification rather than exhaustive enumeration. If this construction established absolute limits, angels would be restricted to a maximum of four wings, which 35:1 explicitly contradicts. The linguistic consistency demands that both verses employ the same enumerative function which provides practical examples within a broader principle rather than establishing divine ceilings.

When the Quran intends specific numerical restrictions, it employs unambiguous language such as “أَرْبَعَةَ شُهَدَاءَ” (arba’ata shuhada’a – “four witnesses”) in 24:4, or “ثَلَاثَةَ قُرُوءٍ” (thalathata quru’in – “three menstruations”) in 2:228, using cardinal numbers with definitive grammatical constructions. The “mathna wa thulatha wa ruba’a” construction appears exclusively in contexts where the Quran provides practical examples rather than absolute boundaries, as demonstrated by the angels’ wings verse and its explicit addition clause.

The consensus among Islamic historians places the revelation of Surah 4 (including 4:3) during the early Medinan period, approximately 3-4 AH. However, Prophet Muhammad’s marriages continued well beyond this period, with most of his nine wives being married after the revelation of this verse. The tradition claims this order:

- Khadijah (died 619 CE, before Hijra)

- Sawdah (married 620 CE)

- Aisha (married 623 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

- Hafsah (married 625 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

- Zaynab bint Khuzayma (married 625 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

- Umm Salama (married 626 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

- Zaynab bint Jahsh (married 627 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

- Juwayriyya (married 628 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

- Safiyya (married 629 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

- Umm Habiba (married 629 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

- Maymuna (married 630 CE, after 4:3 revelation)

This chronological evidence demonstrates that the early Submitter community, including the Prophet himself, did not interpret 4:3 as establishing a numerical ceiling, since the majority of his marriages occurred subsequent to the verse’s revelation (assuming there is truth to these marriages). Suppose the Quran intended to establish a maximum. In that case, Arabic grammar provides clear constructions for absolute limits, such as “لا يَتَجَاوَزُ أَرْبَعًا” (la yatajawazu arba’an – “not exceeding four”) or “حَدُّهُ أَرْبَعٌ” (hadduhu arba’un – “its limit is four”). The absence of such definitive limiting language in 4:3 is linguistically significant and supports the exemplification interpretation.

Traditionalists Abuse

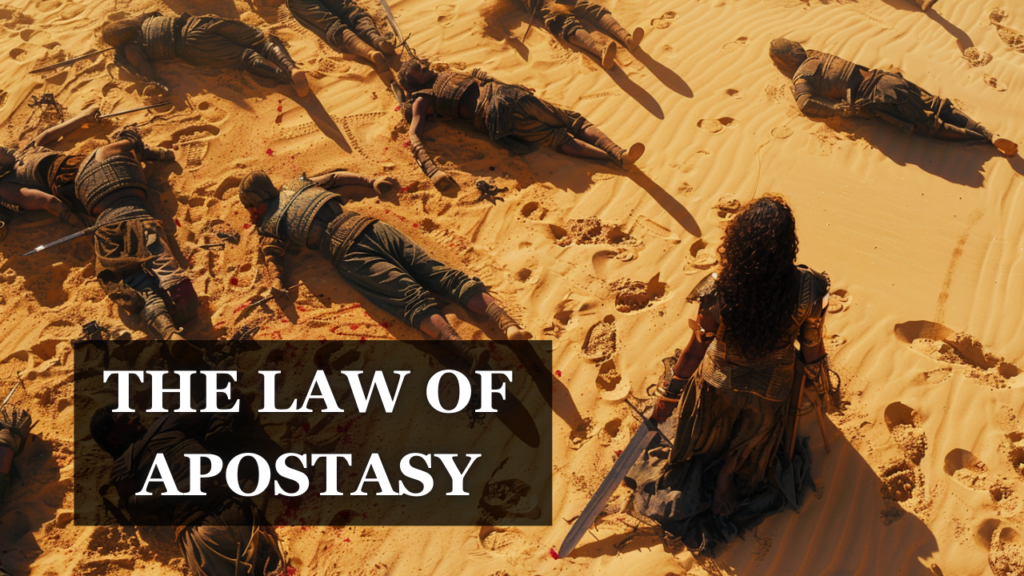

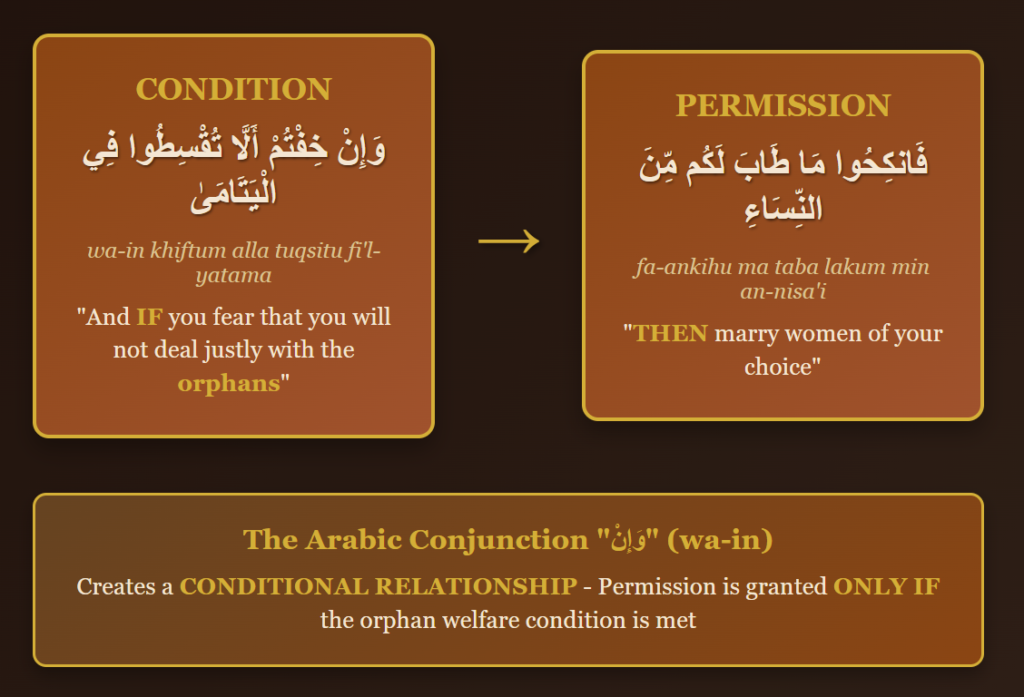

The contextual analysis of Quran 4:3 reveals the verse explicitly frames polygamous marriage within the context of orphan care, not personal gratification. The complete verse states:

“وَإِنْ خِفْتُمْ أَلَّا تُقْسِطُوا فِي الْيَتَامَىٰ فَانكِحُوا مَا طَابَ لَكُم مِّنَ النِّسَاءِ مَثْنَىٰ وَثُلَاثَ وَرُبَاعَ”

“If you deem it best for the orphans, you may marry their mothers—you may marry two, three, or four.”

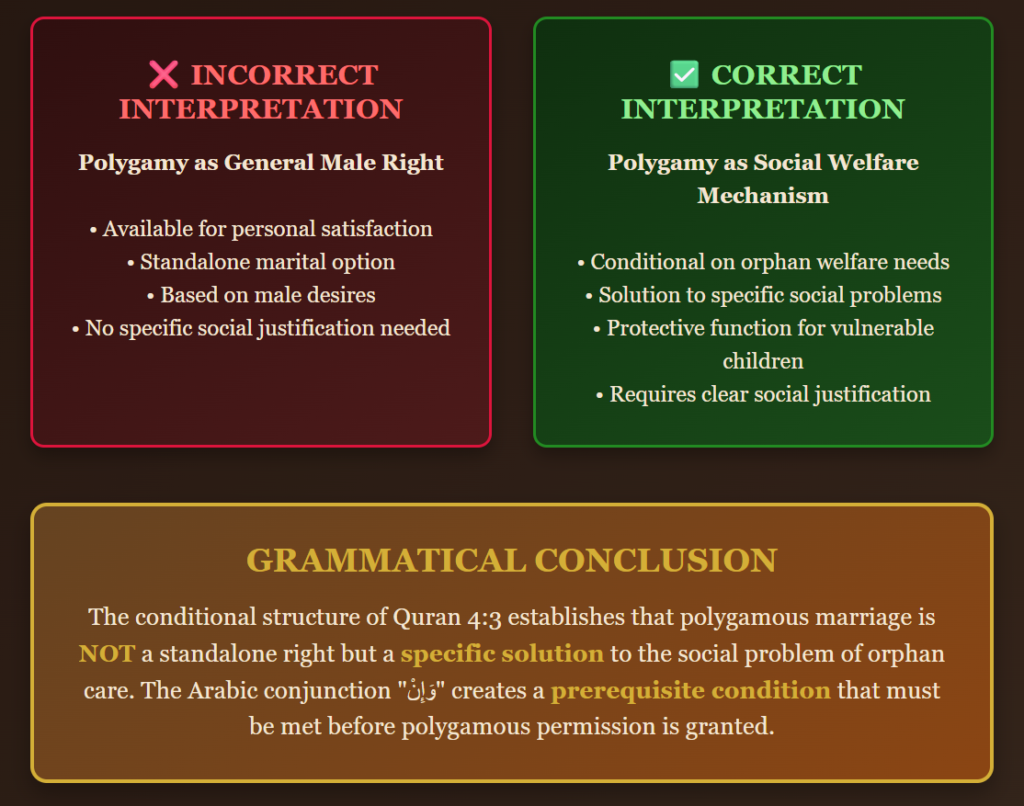

This conditional framework establishes orphan welfare as the primary justification for polygamous arrangements, fundamentally challenging the notion that polygamy exists as a general marital option for male satisfaction. The Arabic conjunction “وَإِنْ” (wa-in – “and if”) creates a conditional relationship between the fear of injustice toward orphans and the permission for polygamy. This grammatical structure indicates that polygamous marriage is not a standalone right, but a specific solution to a particular social problem: the care and protection of orphaned children.

The orphan-centered interpretation establishes several crucial limitations on polygamous practice:

- Circumstantial Requirement: Polygamy becomes permissible only when orphan welfare is at stake, not as a general marital option

- Protective Function: The primary purpose shifts from male satisfaction to child protection and family stability

- Community Responsibility: The verse addresses collective social obligations rather than individual desires

Polygamy was never encouraged as an ideal or right, but rather permitted under tight ethical conditions, with the priority being fairness and protection for the vulnerable. Traditionalist interpretations have abstracted this verse from its ethical and social grounding. By treating polygamy as a general male entitlement, many have ignored the Quran’s warnings about injustice and emotional harm. Some have gone so far as to justify polygamous practices that directly contradict the Prophet’s Quranic duty to follow the revelation (10:15), using hadith to override clear Quranic conditions.

This misreading hasn’t just reshaped theology. It’s had real consequences. Women in many communities have borne the burden of these distortions: entering marriages without informed consent, experiencing unequal treatment, and being told that their suffering is part of a divinely sanctioned order. The original Quranic concern (avoiding harm) has been sidelined, replaced by legalistic loopholes and social norms that run counter to the Quran. Here it from them: