In Islamic hadith studies, a mudalis (مدلس) is a transmitter who commits tadlīs (تدليس), which is a form of concealment or misrepresentation in the chain of narration.

There are primarily two types of tadlīs:

- Tadlīs al-isnad: When a narrator claims to have heard a hadith directly from someone they met but didn’t actually hear it from them directly.

- Tadlīs al-shuyukh: When a narrator refers to their teacher by an unfamiliar name, description, or lineage that obscures their identity.

When a transmitter is classified as a mudalis, it raises concerns about the reliability of their narrations. Hadith scholars carefully scrutinize such transmitters’ reports, especially when they use ambiguous terms like “from” (عن) instead of explicitly stating “I heard” (سمعت). The implications vary depending on the severity and frequency of tadlīs. Some mudalis narrators are still considered trustworthy when they clearly state direct transmission, while extensive tadlīs can significantly weaken a transmitter’s credibility.

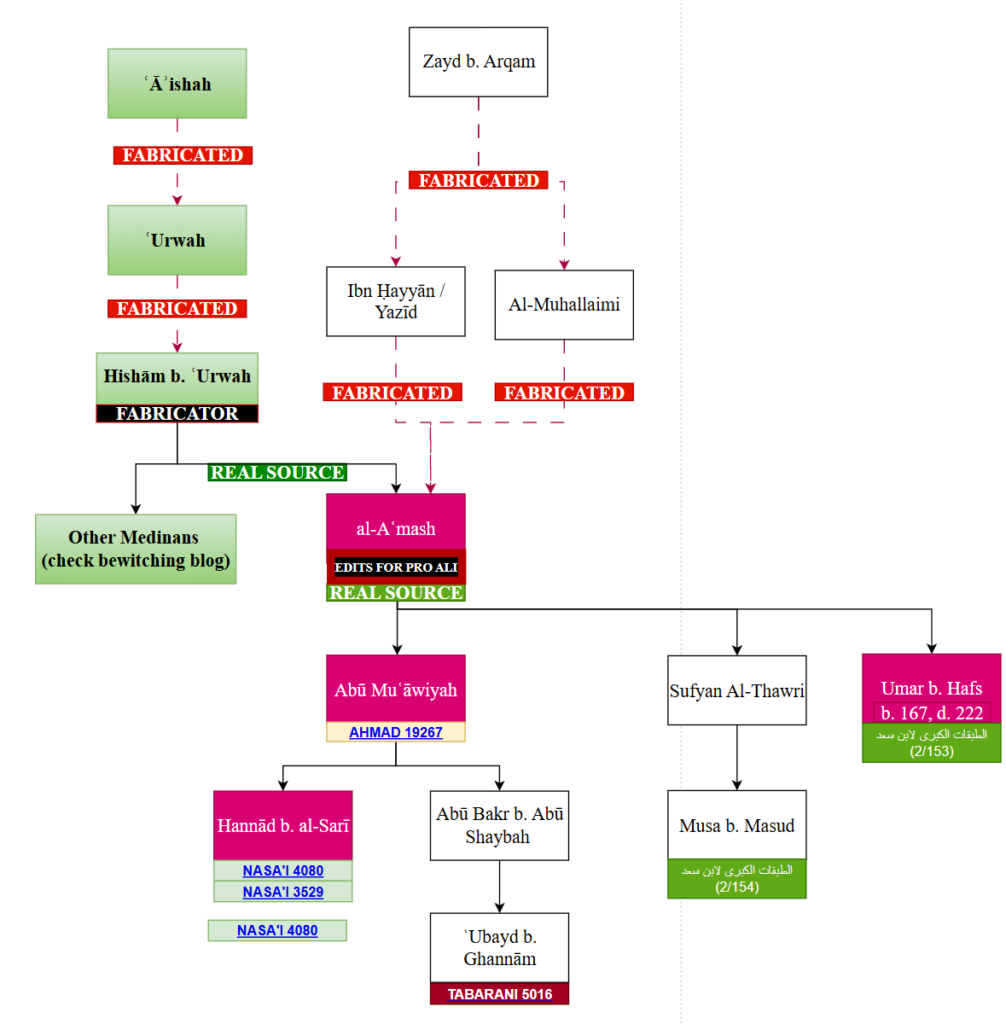

A curious phenomenon exists in the transmission history between two prominent narrators: Hisham ibn Urwa and the renowned Kufan scholar, Sulaiman al-A’mash. In a previous analysis, I examined the hadith describing the alleged bewitchment of Prophet Muhammad. This narration was extensively propagated through Hisham ibn Urwa’s chains of transmission. The account functioned as a polemic against the Jewish community of Medina, advancing the narrative that a local Jewish man had bewitched the Prophet, while simultaneously emphasizing divine intervention that protected Muhammad from the full effects of this sorcery.

What makes this transmission pattern particularly intriguing is that a remarkably similar narrative was circulating in Kufa during the same period. However, these Kufan versions conspicuously lack any citation of Hisham ibn Urwa in their isnad chains, despite his central role in disseminating this tradition elsewhere. This discontinuity raises important questions about the transmission history and regional development of this particular hadith.

The core structure of the narration remains the same between these two narrations, despite details being slightly different. The question is, how did the same incident, become narrated in two different cities, roughly 1,500 km away from each other? The answer is clear: tadlīs.

A Brief History of Al-A’mash

Al-A‘mash (Sulaymān ibn Mahrān, d. 148 AH) was a renowned hadith scholar and transmitter from Kufa. He was known for his strong memory, piety, asceticism, and sharp wit. He studied under some of the greatest scholars of his time and became a key figure in transmitting hadith, with major scholars like Sufyan al-Thawri and Abu Hanifa among his students. Despite his personality, he was highly respected for his knowledge and devotion.

However, he was accused of tadlīs (concealing the identity of narrators in hadith transmission). He was specifically classified as a mudallis of the first category (tadlīs al-isnād), meaning he sometimes narrated hadith with ambiguous wording (e.g., using “from” instead of “heard from”), which could obscure whether he directly heard the hadith from his teacher or not. Because of this, some scholars required explicit confirmation of direct transmission (sama‘) when taking hadith from him. Despite this, his narrations are widely accepted, especially when he explicitly states he heard the hadith directly. His reliability is upheld by major scholars, and he remains a foundational figure in hadith transmission.

Ali ibn al-Madini said: He transmitted around 1,300 hadiths. He saw Anas ibn Malik and narrated from him, though with an element of tadlīs (concealment in hadith transmission). Despite his great scholarly status, he was known for practicing tadlīs. He narrated from Abdullah ibn Abi Awfa in the same manner. He also narrated from Abu Wa’il, Zayd ibn Wahb, Abu ‘Amr al-Shaybani, Ibrahim al-Nakha‘i, Sa‘id ibn Jubayr, Abu Salih al-Samman, Mujahid, Abu Dhibyan, Khaythama ibn Abd al-Rahman, Zur ibn Hubaysh, Abd al-Rahman ibn Abi Layla, Kumayl ibn Ziyad, al-Ma‘rur ibn Suwayd, al-Walid ibn Ubadah ibn al-Samit, Tamim ibn Salamah, Salim ibn Abi al-Ja‘d, Abdullah ibn Murrah al-Hamdani, ‘Amarah ibn ‘Umayr al-Laythi, Qays ibn Abi Hazim, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Rahman ibn Yazid al-Nakha‘i, Hilal ibn Yasaf, Abu Hazim al-Ashja‘i (Salman), Abu al-‘Aliyah al-Riyahi, Ismail ibn Raja’, Thabit ibn ‘Ubayd, Abu Bishr, Habib ibn Abi Thabit, al-Hakam, Dharr ibn ‘Abdullah, Ziyad ibn al-Husayn, Sa‘id ibn ‘Ubaydah, al-Sha‘bi, al-Manhal ibn ‘Amr, Abu Sabr al-Nakha‘i, Abu al-Safar al-Hamdani, ‘Amr ibn Murrah, Yahya ibn Wuthab, and many others among the senior Tabi‘un (successors of the companions), as well as others.

Many narrated from him, including: al-Hakam bin ‘Utayba, Abu Ishaq al-Sabi‘i, Talha bin Musarrif, Habib bin Abi Thabit, ‘Asim bin Abi al-Nujud, Ayyub al-Sakhtiyani, Zayd bin Aslam, Safwan bin Sulaym, Suhayl bin Abi Salih, A‘ban bin Taghlib, Khalid al-Hadha’, Sulaiman al-Taymi, Isma‘il bin Abi Khalid, and others, many of whom were his peers. Also, Abu Hanifa, al-Awza‘i, Sa‘id bin Abi ‘Aruba, Ibn Ishaq, Shu‘ba, Ma‘mar, Sufyan, Shayban, Jarir bin Hazim, Zaidah, Jarir bin ‘Abd al-Hamid, Abu Mu‘awiya, Hafs bin Ghiyath, ‘Abdullah bin Idris, ‘Ali bin Mushir, Waki‘, Abu Usama, Sufyan bin ‘Uyaynah, and many more. The last to narrate from him was Yahya bin Hashim al-Samsar.

Hisham’s Move To Kufa – Did He Meet Al-A’mash?

It’s clear that Al-A’mash was known for being a mudalis, but did he commit tadlis for the bewitching hadith? –

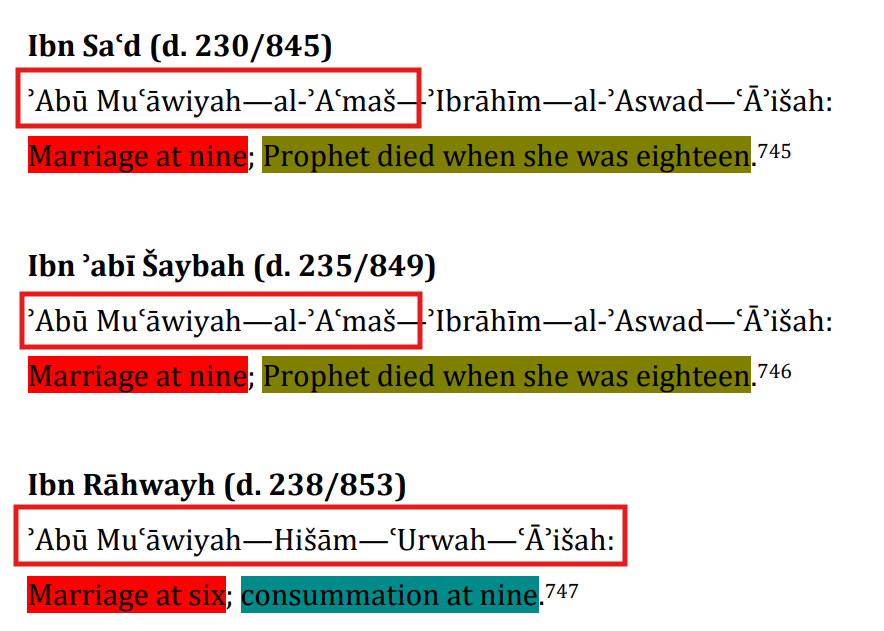

… الكبرى للنسائي:٣٥٢٩ – أَخْبَرَنَا هَنَّادُ بْنُ السَّرِيِّ عَنْ أَبِي مُعَاوِيَةَ عَنْ الْأَعْمَشِ عَنْ ابْنِ حَيَّانَ يَعْنِي يَزِيدَ عَنْ زَيْدِ بْنِ أَرْقَمَ

… النسائي:٤٠٨٠ – أَخْبَرَنَا هَنَّادُ بْنُ السَّرِيِّ عَنْ أَبِي مُعَاوِيَةَ عَنِ الأَعْمَشِ عَنِ ابْنِ حَيَّانَ يَعْنِي يَزِيدَ عَنْ زَيْدِ بْنِ أَرْقَمَ

… أحمد:١٩٢٦٧ – حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو مُعَاوِيَةَ حَدَّثَنَا الْأَعْمَشُ عَنْ يَزِيدَ بْنِ حَيَّانَ عَنْ زَيْدِ بْنِ أَرْقَمَ

… الطبراني:٥٠١٦ – حَدَّثَنَا عُبَيْدُ بْنُ غَنَّامٍ ثنا أَبُو بَكْرِ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ ثنا أَبُو مُعَاوِيَةَ عَنِ الْأَعْمَشِ عَنْ يَزِيدِ بْنِ حَيَّانَ عَنْ زَيْدِ بْنِ أَرْقَمَ

Al-A’mash consistently employs the ambiguous transmission term “from” (عن) rather than the definitive “I heard” (سمعت) across these narrations—a textbook indicator of tadlīs (concealment). This evidence decisively refutes Al-A’mash’s claim of direct transmission from Yazid ibn Hayyan. The mystery of how Al-A’mash acquired this Medinan bewitchment tradition is solved through a simple yet profound reversal: Hisham ibn Urwa was not the recipient but the source. The transmission flowed from Hisham to Al-A’mash during Hisham’s Kufan residence, revealing Al-A’mash’s deliberate obscuring of his true source in the transmission chain.

| Critic | Criticism | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Malik ibn Anas | Did not approve of Hisham, especially his narrations for the people of Iraq. Criticized him for changing the way he narrated reports over his three visits to Kufa. | Tahdhib al-Tahdhib (4/275) |

| Ya’qub ibn Shaybah | Reliable and trustworthy, but after moving to Iraq, he expanded his narrations from his father, which was denounced by the people of his region. His leniency was in transmitting from his father reports he had heard from others about his father. | Tahdhib al-Tahdhib (4/275) |

| Ibn Kharrash | Stated that Malik did not approve of Hisham’s narrations for the people of Iraq. Highlighted changes in Hisham’s transmission style over his three visits to Kufa, evolving from “my father told me” to “from my father, from Aisha.” | Tahdhib al-Tahdhib (4/275) |

| Malik ibn Anas (expanded) | Criticized him specifically for narrating to the Iraqis in ways that were not consistent with his usual standards when in Medina. | Tahdhib al-Tahdhib (4/275)* |

Hishām ibn ‘Urwa ibn al-Zubayr, an Arab, first presented himself to al-Manṣūr in Kufa and later joined him in Baghdad, where he passed away in 146/763 (IS, VII 2, p. 67). The quality of his hadith transmissions is said to have deteriorated after his move to Iraq, an opinion shared by Mālik … (See: al-Dhahabī, Siyar A‘lam al-Nubalā’, VI, p. 35; Juynboll, Encyclopedia of Canonical Hadith, p. 184].

Hisham ibn Urwa’s relocation to Kufa establishes an incontrovertible connection with Sulaiman al-A’mash. The notion that Hisham—a preeminent Medinan transmitter with direct access to prophetic traditions through his father’s connection to Aisha—would not have engaged with al-A’mash, Kufa’s foremost hadith authority, defies logical reasoning. This connection is further cemented by documented evidence showing Hisham transmitted hadith to al-A’mash’s student (Abu Muawiyah), confirming a direct transmission pathway in the scholarly network. These geographical, hierarchical, and documented links form an irrefutable chain of association between these two pivotal figures in hadith transmission.

Islamic Historical Memory

Al-A’mash’s deliberate exclusion of Hisham ibn Urwa from his isnad likely stemmed from the complex sectarian dynamics of Kufa. As a prominent Kufan transmitter operating in an environment with strong pro-Ali and Ahlul Bayt sympathies, Al-A’mash faced a calculated risk when handling traditions originating from Aisha—whose political tensions with Ali were well-documented historical fact. Citing Hisham ibn Urwa, Aisha’s grand-nephew by marriage, would have immediately flagged these narrations within Kufa’s scholarly circles as coming from the “Medinan-Umayyad” transmission network potentially hostile to Ali’s legacy.

This tactical omission reflects Al-A’mash’s pragmatic approach to knowledge transmission in a politically charged environment. By obscuring the Aisha-Hisham connection through tadlīs, he could disseminate these traditions while minimizing resistance from his predominantly Shi’i-leaning audience. The contrast with Abu Muawiyah, who openly acknowledged Hisham, underscores that such concerns varied among transmitters based on their individual standing and audience relationships within Kufa’s complex sectarian landscape.

A Concerning Conclusion

Al-A’mash’s transmission of the bewitchment hadith represents a deliberate case of tadlīs designed to obscure its true Medinan origins. When Hisham ibn Urwa relocated to Kufa, he brought this tradition directly to Al-A’mash, the region’s preeminent transmitter. Al-A’mash, recognizing the narrative’s authenticity but anticipating resistance from his Kufan audience due to its connection to Aisha, made a calculated decision to substitute the isnad.

By fabricating an alternative chain of transmission, Al-A’mash effectively laundered the hadith’s provenance. This strategic substitution allowed him to present the content—which he likely personally deemed credible—while removing the problematic association with Aisha, her nephew, and grand-nephew, that would have triggered immediate skepticism among his pro-Ali audience. This documented case of transmission manipulation raises profound questions about the integrity of Al-A’mash’s broader corpus. If he willingly altered the chain for this politically sensitive chain/hadith, it establishes a troubling precedent that potentially extends to other narrations. The question becomes not whether Al-A’mash received additional material from Hisham, but rather how many other Medinan traditions he similarly reattributed to more palatable sources.

This revelation exposes a significant blind spot in classical hadith criticism. Despite their methodological rigor, the muhadithūn failed to detect this specific instance of transmission fraud—suggesting that similar cases may have escaped scrutiny throughout the canon. The implications extend beyond this single hadith to potentially numerous traditions where Al-A’mash may have systematically obscured Medinan sources unfavorable to Kufan sectarian sensibilities.

👍

Pingback: Sahih Bukhari: Breaking an Idol – Thinking islam