Tracing a Hadith to its Talmudic Source

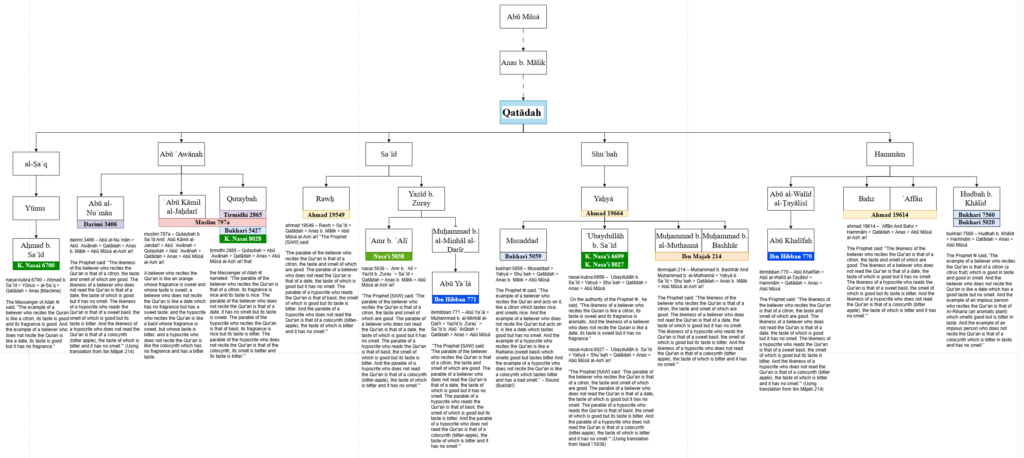

Here is a fascinating case involving Qatada – a controversial hadith transmitter from Basra who lived in the 8th century, borrowing hadith from Talmudic sources. What caught my attention was a hadith where the Prophet Muhammad supposedly compares believers to different fruits based on whether they read the Quran and how it affects their “taste” and “fragrance.” But here’s the thing – this exact parable shows up earlier in Jewish texts, specifically in Vayikra Rabbah (a commentary on Leviticus).

Musnad of Ahmad

ahmad:19664 – Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd > Shuʿbah > Qatādah > Anasʿ> Abū Mūsá – The Prophet said:

“The likeness of the believer who recites the Qur’an is that of a citron, the taste and smell of which are good.

The likeness of a believer who does not read the Qur’an is that of a date, the taste of which is good but it has no smell.

The likeness of a hypocrite who reads the Qur’an is that of a sweet basil, the smell of which is good but its taste is bitter.

And the likeness of a hypocrite who does not read the Qur’an is that of a colocynth (bitter apple), the taste of which is bitter and it has no smell.’“

Vayikra Rabbah 30:12

Another matter: “The fruit of a pleasant [hadar] tree” – this is Israel; just as the citron has taste and has fragrance, so Israel has people among them who have Torah and have good deeds.

“Branches of date palms” – this is Israel; just as the date palm has taste but has no fragrance, so Israel has people among them who have Torah but do not have good deeds.

“A bough of a leafy tree” – this is Israel; just as the myrtle has fragrance but has no taste, so Israel has people among them who have good deeds but do not have Torah.

“Willows of the brook” – this is Israel; just as the willow has no taste and has no fragrance, so Israel has people among them who do not have Torah and do not have good deeds.

The Undeniable Talmudic Origins of Qatada’s Fruit Metaphor

Looking closely at the two texts side by side, the evidence for Qatada’s borrowing from Talmudic sources becomes overwhelming. This isn’t merely a case of similar ideas emerging independently – we’re seeing a deliberate transplantation of a Jewish metaphorical framework into Islamic tradition.

Structural Parallels

The core metaphorical structure in both texts is identical: four types of fruits representing four types of people, with each fruit possessing a specific combination of taste and fragrance. This specific four-part taxonomy using the same sensory qualities (taste and smell) appears in both texts with remarkable fidelity.

- Citron (etrog): Has both taste and fragrance

- Date palm: Has taste but no fragrance

- Myrtle/sweet basil: Has fragrance but no taste

- Willow/colocynth: Has neither taste nor fragrance

Such precise structural parallels cannot be coincidental, especially given the relative obscurity of this specific metaphorical framework. The odds of independently developing this exact system with the same sensory qualities is vanishingly small. What’s particularly revealing is how Qatada adapted this Jewish teaching to fit Islamic theology. He cleverly repurposed the metaphor by:

- Replacing the Jewish focus on “Torah and good deeds” with the Islamic focus on “believers and Qur’an recitation”

- Maintaining the same sensory qualities (taste and smell) as evaluation criteria

- Preserving the four-part structure while subtly shifting the categories to fit Islamic concepts of believers and hypocrites

This systematic adaptation demonstrates conscious borrowing rather than unconscious influence. Qatada didn’t just remember a similar idea; he deliberately reworked Jewish material to serve Islamic purposes.

Transmission History

The hadith attributes this teaching to the Prophet Muhammad through a chain leading back through Anas and Abu Musa – a classic example of retroactive isnad fabrication. This practice was unfortunately common in this period, especially among Basran transmitters like Qatada. By creating a chain of transmission from the Prophet → Abu Musa → Anas → Qatada → Shu’bah → Yahya ibn Sa’id → Ahmad, Qatada effectively “Islamized” what was clearly Talmudic material.

What makes this particularly suspicious is that we have multiple transmitters allegedly receiving this tradition from Qatada, suggesting a deliberate effort to establish the hadith’s credibility through seeming multiple attestation. This borrowing must be understood within the broader context of early Islamic scholarly environments, particularly in Basra. As a center of learning where Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions intersected, Basra provided ample opportunity for transmitters like Qatada to encounter and adapt non-Islamic material. Qatada, known for his extensive knowledge of various traditions, would have had access to Jewish texts and teachings, either directly or through converts familiar with Talmudic literature.

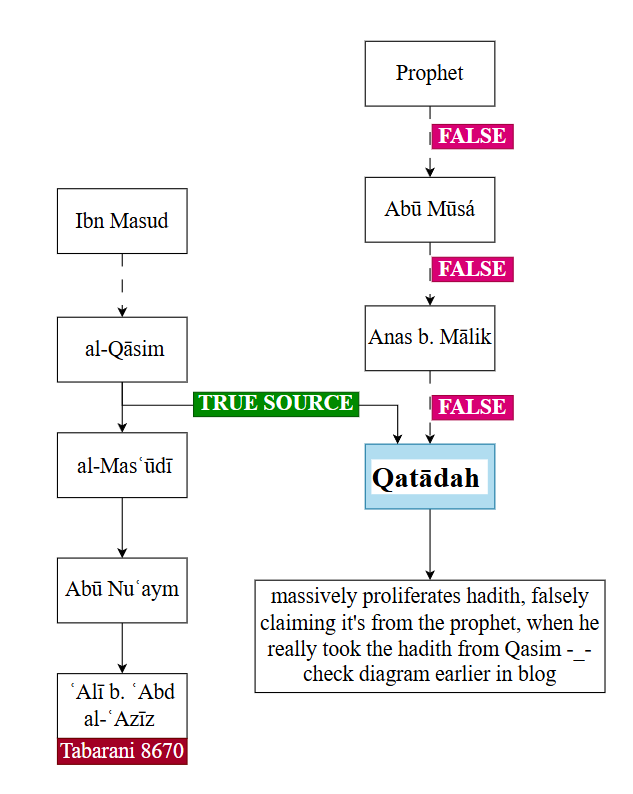

But the discovery of Ibn Mas’ud’s version adds another crucial dimension to this analysis. This variant, transmitted through al-Ṭabarānī (ḥadīth #8670), presents essentially the same allegorical framework but with a critical difference – it’s attributed only to the companion ‘Abdallāh ibn Mas’ūd and makes no claim of prophetic origin. The transmission chain through al-Qāsim (Ibn Mas’ūd’s grandson) places this version in Kufa, not Basra, revealing how the tradition likely traveled between these intellectual centers.

tabarani:8670 –ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz > Abū Nuʿaym > al-Masʿūdī > al-Qāsim

Abdullah said, “The example of one who recites the Qur’an but does not act upon it is like that of a fragrant flower with no taste.

And the example of one who acts upon the Qur’an but does not recite it is like that of a date with a pleasant taste but no fragrance.

And the example of one who learns the Qur’an and teaches it is like that of a fragrant and tasty citrus fruit.

And the example of one who neither recites the Qur’an nor acts upon it is like that of a bitter gourd with a foul taste and smell.”

Ibn Mas’ud’s version preserves stronger parallels to the original Talmudic text while applying the framework to Quranic recitation and practice. The terms are nearly identical – comparing those who recite but don’t practice to aromatic plants with pleasant smell but no taste, those who practice but don’t recite to dates with taste but no smell, those who both teach and learn to citron with both qualities, and those who neither recite nor practice to colocynth with neither quality. This intermediate version exposes Qatada’s methodology: he wasn’t directly importing from Jewish tradition, but rather “elevating” an existing companion saying by fabricating a prophetic isnad. This process of “raf’ al-ḥadīth” (raising a statement’s status to prophetic) was precisely what early ḥadīth critics like Juynboll suspected Qatada of doing regularly. The fruit allegory provides a textbook example of this process – a saying that began as Jewish wisdom, entered Islamic discourse through Ibn Mas’ud without prophetic attribution, then was retrospectively assigned to Muhammad by Qatada and disseminated through multiple transmission channels.

The strategic placement of Anas and Abū Mūsā in Qatada’s fabricated chain served to distance the tradition from its actual origins while providing the appearance of reliable prophetic transmission. The multiple students allegedly receiving this tradition from Qatada then further embedded it in hadith literature through seeming independent attestation.

Textbook Case of Sahih Al-Yahud Material In Sahih Hadith Corpus

This case provides a textbook example of how certain hadith actually originated: not with the Prophet Muhammad, but through a complex process of transmission and transformation across religious and geographical boundaries. The complete transmission history can be traced from Jewish sources through companion sayings to prophetic hadith:

First, the allegory appears in the Jewish Vayikra Rabbah 30:12, using four plants (citron, date palm, myrtle, and willow) to represent four types of Jews based on their possession of Torah knowledge and good deeds.

This framework then entered Islamic discourse as a companion saying attributed to Ibn Mas’ud in Kufa, who applied the same four-part structure to Quranic engagement rather than Torah observance, but crucially made no claim of prophetic origin. This version was transmitted through his grandson al-Qasim.

Finally, Qatada in Basra transformed this companion saying into a prophetic hadith by fabricating a chain of transmission through Anas and Abu Musa back to Muhammad. He then disseminated this “elevated” version through multiple students, creating the appearance of independent attestation to strengthen its credibility.

This evolutionary pathway – from Talmudic text to companion saying to prophetic hadith – reveals the sophisticated mechanisms by which external material was incorporated into Islamic tradition. Rather than simply attributing borrowed material directly to the Prophet, the process often involved intermediate steps and strategic isnad fabrication. The fruit allegory serves as a revealing window into the actual historical development of hadith literature, demonstrating how critical analysis can uncover the true origins of traditions that became foundational to Islamic religious thought.

Pingback: Ṣaḥīḥ al-Yahūd – Being Merciful To Inhabitants of Earth - HadithCritic