In recent years, a growing number of Muslims have acknowledged the faults of the hadith sciences and just Sunnism in general. Many have adopted the Quran alone position, but there’s a growing group who have embraced something called “Quran-centrism”. It’s the idea that we should accept or reject hadith based on whether they align with or contradict the Quran. On the surface, this approach appears more rational and objective than traditional hadith scholarship. After all, why wouldn’t we use the Quran, which Muslims & Submitters believe to be the direct word of God, as our standard for evaluating other religious texts?

But beneath this seemingly logical methodology lies a web of contradictions and problems that may actually make hadith evaluation less reliable, not more. The reality is that Quran-centrism doesn’t solve the fundamental issues of traditional Islamic scholarship. All it does is simply move them to a different location while creating entirely new dilemmas.

Paradox 1: Subjectivity

The most glaring problem with Quran-centrism is what we might call the “subjectivity paradox.” Advocates present their approach as objective and rational, claiming they’re simply checking whether hadith align with the clear teachings of the Quran. But this process is entirely dependent on one’s personal interpretation of Quranic verses; interpretations that are just as subjective as any traditional scholarly opinion.

Here’s an example:

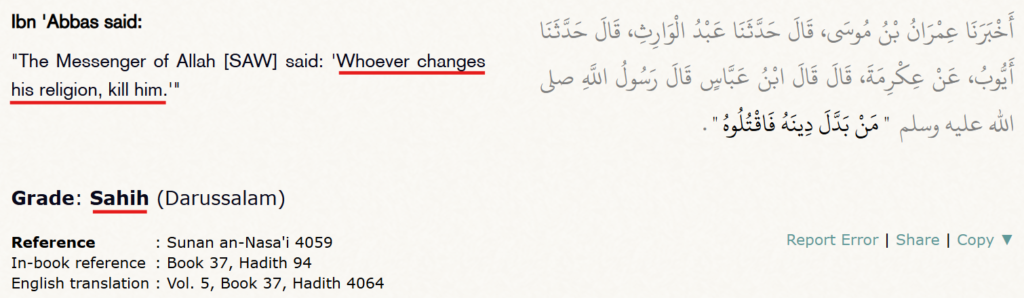

ANTI-APOSTASY EXECUTION

When evaluating hadith about executing those who leave Islam, some Quran-centrists point to verse 2:256:

[2:256] There shall be no compulsion in religion: the right way is now distinct from the wrong way. Anyone who denounces the devil and believes in God has grasped the strongest bond; one that never breaks. God is Hearer, Omniscient.

They argue that threatening someone with death for leaving the faith is inherently compulsive, directly contradicting this Quranic principle. Therefore, they conclude that any hadith supporting apostasy punishment must be fabricated.

PRO-APOSTASY EXECUTION

Other Quran-centrists, however, point to verses like 9:5 and 5:33, interpreting them as supporting severe punishment for those who oppose Islam. Using the exact same methodology—comparing hadith to Quranic teachings—they reach the opposite conclusion and accept the apostasy hadith as authentic.

[5:33] The just retribution for those who fight GOD and His messenger, and commit horrendous crimes, is to be killed, or crucified, or to have their hands and feet cut off on alternate sides, or to be banished from the land. This is to humiliate them in this life, then they suffer a far worse retribution in the Hereafter.

[9:5] Once the Sacred Months are past, (and they refuse to make peace) you may kill the idol worshipers when you encounter them, punish them, and resist every move they make. If they repent and observe the Contact Prayers (Salat) and give the obligatory charity (Zakat), you shall let them go. GOD is Forgiver, Most Merciful.

The result is a completely subjective system where people accept or reject narrations based on what they personally believe aligns with the Quran. Each person becomes their own religious authority, claiming that their understanding of “what contradicts the Quran” is the correct one. But this raises an obvious question: who exactly decides what the correct understanding of the Quran is?

Paradox 2: The Circular Reasoning Trap

This subjectivity leads directly to a circular reasoning problem that undermines the entire Quran-centric methodology. The process works like this: a person interprets the Quran in a particular way, then judges a hadith to be authentic if it agrees with that interpretation. But their Quranic interpretation was never objectively validated in the first place. They’re using one subjective view (their reading of the Quran) to validate another subjective claim (the hadith’s authenticity). Take this example:

Imagine someone who falsely believes that Boston is the capital of the United States. If they encounter a historical document claiming “George Washington declared the nation’s capital to be in New England,” they might think: “This aligns with my understanding that Boston is the capital, so this document must be authentic.” But since their foundational belief is wrong, their authentication of the document is also wrong.

The same dynamic occurs with Quran-centrism. If someone has a flawed interpretation of a Quranic passage, they will evaluate hadith authenticity based on that flawed understanding. The hadith evaluation becomes corrupted from the start because the measuring stick itself is unreliable.

Paradox 3: Abandoning Sunni-Historical Verification

I’ve mentioned in many videos on the HadithCritic YouTube channel how the various hadith methodological sciences are highly subjective and weak. In the case of Quran-centrism, an extremely troubling aspect is its complete abandonment of historical verification. Traditional hadith scholarship, whatever its flaws, at least attempted to verify whether the Prophet Muhammad actually said or did what a hadith claims. Quran-centrists, by focusing solely on content alignment, make the dangerous assumption that ideological consistency equals historical authenticity. This creates a bizarre situation where a hadith with transmission gaps of 200, 400, or even 600 years can be accepted as “authentic” simply because its content doesn’t obviously contradict someone’s interpretation of the Quran. A clever forger could easily fabricate sayings about kindness, charity, or moral behavior that would pass any Quranic filter, yet Quran-centrists would have no way to detect such fabrications.

Paradox 4: The Theological Contradiction

There’s also a fundamental theological contradiction at the heart of Quran-centrism. If Quran-centrists believe that certain hadith are genuinely from the Prophet, they are attributing prophetic authority to those sayings. But if they do this without any historical verification, they are making a religious claim with absolutely no evidence. They’re essentially saying “This is what the Prophet said” while admitting they have no idea whether he actually said it.

On the other hand, if they don’t believe the hadith actually comes from the Prophet, then why quote it at all in religious discussions? Many Quran-centrists will say things like “Well, I don’t know if the Prophet actually said this, but it’s good advice that aligns with Quranic values, so I’ll accept it.” But consider what this means: if you don’t believe a hadith truly comes from the Prophet but you accept it for its moral value, then what makes that hadith any more special than good moral teachings found in literature? Harry Potter teaches about courage and standing up against evil. The Lord of the Rings emphasizes mercy and resisting corruption. These are excellent moral teachings that “align with Quranic values” of justice and righteousness. By Quran-centric logic, should we start quoting Gandalf and Dumbledore in religious discussions?

This absurdity exposes the core problem: either you believe these are actual words of the Prophet Muhammad, in which case you need to verify that claim historically, or you’re just collecting inspirational quotes from various sources, in which case, stop calling them “hadith” and stop giving them religious authority.

Paradox 5: The False Promise of Objectivity & The Logical Conclusion

Ironically, a thorough critique of Quran-centrism points toward an entirely different conclusion than its advocates intended. If both traditional hadith scholarship and Quran-centrism lead to subjective disagreements, and if the Quran claims to be complete and sufficient guidance (6:38: “We have not neglected anything in the Book”), then perhaps the solution isn’t to fix hadith methodology—perhaps it’s to abandon the entire enterprise of hadith authentication altogether. After all, if the Quran truly is the complete guidance from God, why are we so desperate to supplement it with other sources whose authenticity we can never definitively establish? Quran-centrism wants the benefits of hadith without the responsibility of properly verifying them. It’s trying to have it both ways—using external sources for guidance while claiming the Quran alone is sufficient.

The methodology reveals itself as an intellectual compromise that satisfies neither rigorous historical standards nor consistent theological principles. In attempting to solve the problems of traditional Islamic scholarship, Quran-centrism has created a system with all the same flaws plus additional complications of its own making.