One of the most influential hadiths in Islamic legal theory states: “If a judge passes judgment and strives to reach the right conclusion and gets it right, he will have two rewards; if he strives to reach the right conclusion but gets it wrong, he will still have one reward.“

This tradition became a cornerstone of usul al-fiqh (legal methodology), providing divine justification for judicial reasoning (ijtihad) and protecting judges from criticism when their rulings proved incorrect. But a careful analysis of its transmission history reveals troubling patterns that cast serious doubt on its authenticity.

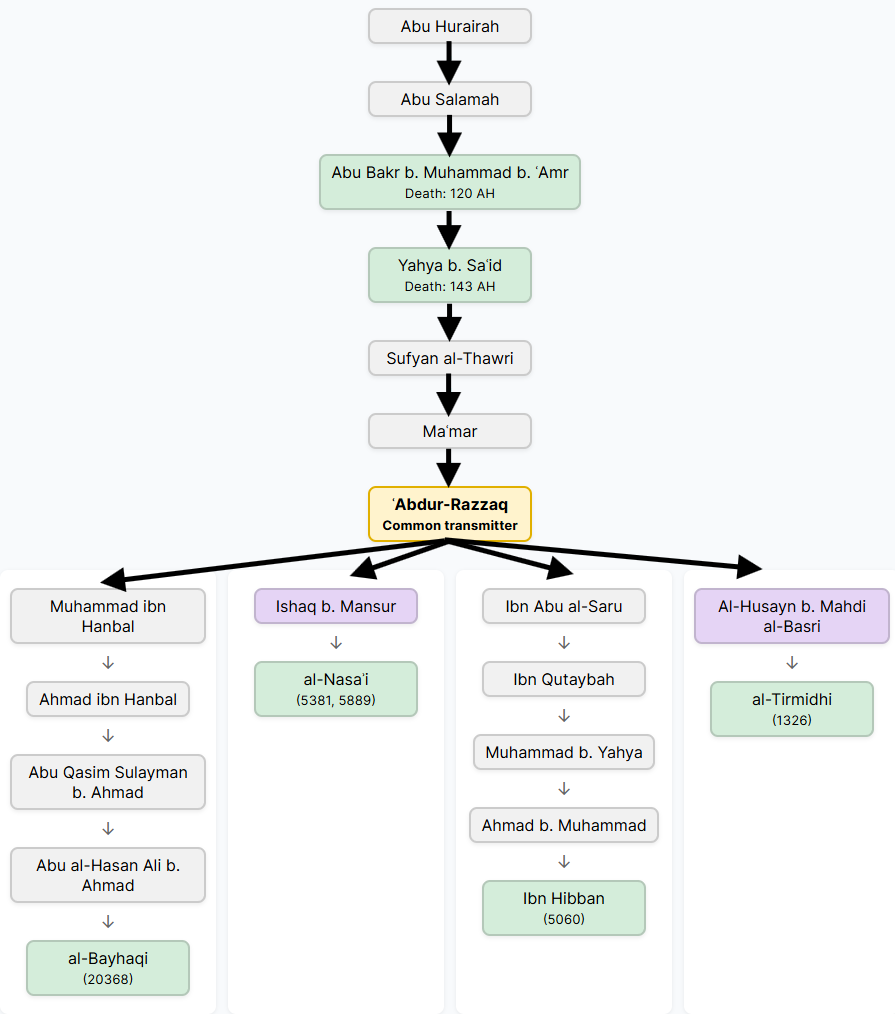

Bundle 1: The Yahya Chain

The first transmission bundle shows:

- Common Link: Abd al-Razzaq al-San’ani (d. 211 AH)

- Key Transmitters: Abu Bakr ibn Muhammad ibn Amr ibn Hazm (d. 120 AH), Yahya ibn Sa’id al-Ansari (d. 143 AH)

- Geographic Origin: Medina (Green blocked names)

- Professional Background: Both Abu Bakr and Yahya were prominent Medinan jurists; Abu Bakr served as judge of Medina under Caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz

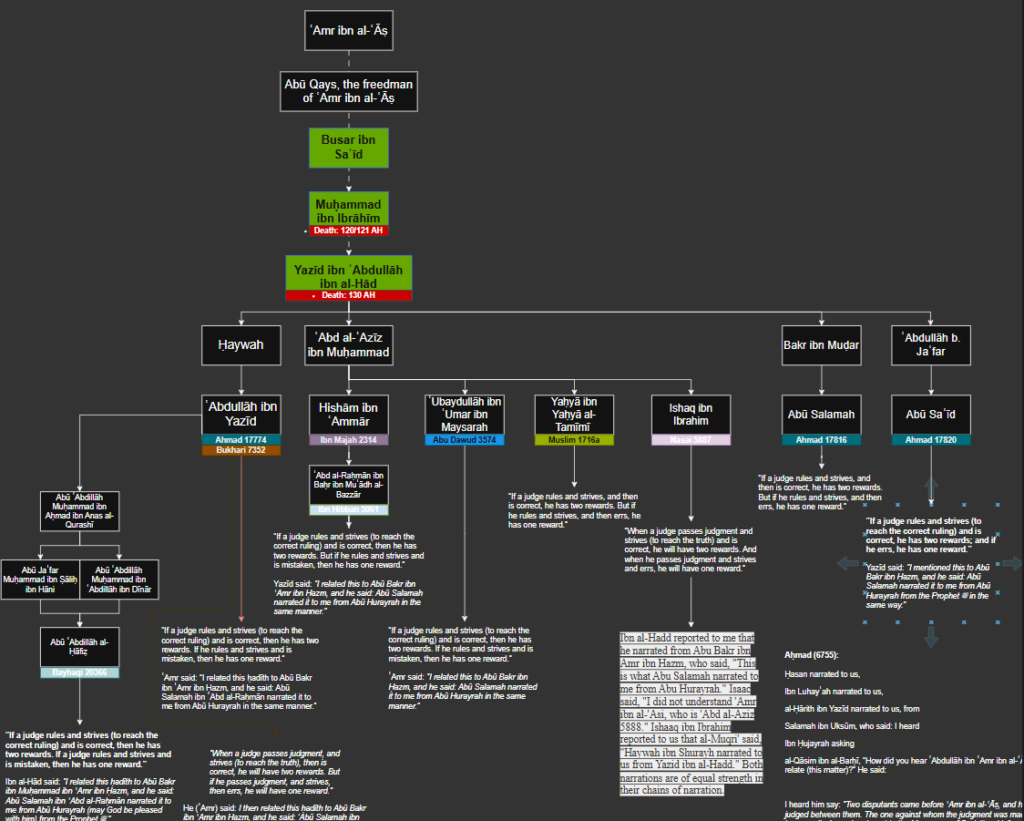

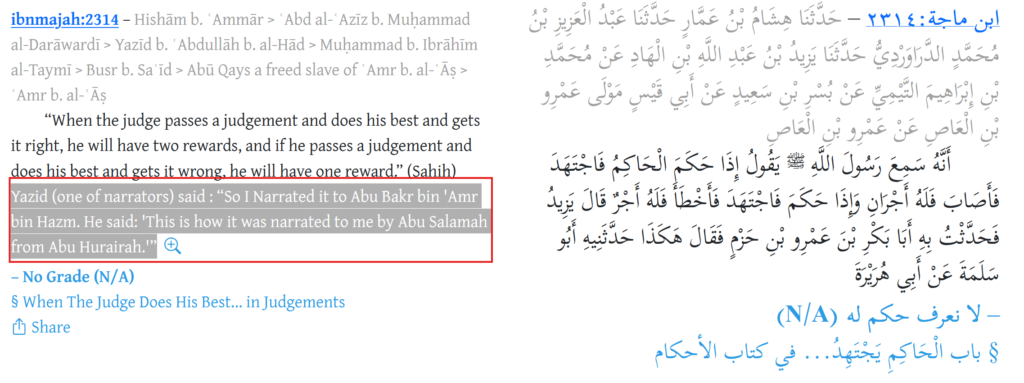

Bundle 2: The Yazid Chain

The second transmission bundle presents:

- Common Link: Yazid ibn Abdullah ibn al-Had (d. 130 AH)

- Key Transmitters: Busar ibn Sa’id, Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Taymi (d. 120/121 AH)

- Critical Addition: Yazid includes a note stating he related this hadith to Abu Bakr ibn Hazm, who confirmed: “Abu Salamah narrated it to me from Abu Hurayrah in the same manner.”

At first glance, this appears to be strong evidence – multiple independent chains converging on the same content, all passing through respected Medinan authorities.

The Malik Test: The Smoking Gun

The most devastating evidence against this hadith’s authenticity comes from what it doesn’t appear in: Imam Malik’s Muwatta. Malik ibn Anas (d. 179 AH) was the definitive compiler of Medinan legal tradition. His Muwatta was specifically designed to preserve the authentic legal practices and hadith of Medina. Consider the implications:

- This hadith allegedly passed through five different Medinan jurists in the early 2nd century AH

- Malik personally knew these scholarly circles and frequently cited Yahya ibn Sa’id al-Ansari in other contexts

- This hadith addresses fundamental questions of judicial methodology – exactly the kind of legal principle Malik would prioritize

- If authentic and circulating among Medinan jurists during Malik’s lifetime, his omission is inexplicable

The silence of the Muwatta on this crucial legal doctrine is damning evidence that the hadith did not exist in early Medinan scholarly circles. Every major transmitter in both bundles was a judge or jurist – precisely the professional class that would benefit from a doctrine providing divine reward even for incorrect rulings:

- Abu Bakr ibn Hazm: Judge of Medina

- Yahya ibn Sa’id: Leading Medinan jurist

- Muhammad ibn Ibrahim: Medinan legal scholar

- Yazid ibn Abdullah: Medinan jurist

This represents a classic case of cui bono – who benefits from this tradition’s existence? The hadith essentially provides religious insurance for judicial decisions, protecting the professional interests of those transmitting it. The transmission structure reveals a concerning pattern:

Bundle 1: Common link at Abd al-Razzaq al-San’ani (d. 211 AH)

Bundle 2: Common link at Yazid ibn Abdullah ibn al-Had (d. 130 AH)

This suggests we may be looking at one bundle influencing the other rather than truly independent transmission. If the hadith originated with Yazid (d. 130 AH), why didn’t Malik (d. 179 AH) encounter it during the nearly 50 years between Yazid’s death and his own? The late convergence at Abd al-Razzaq for Bundle 1 suggests potential back-construction of an alternative chain. The hadith exhibits classic circular reasoning: it’s used to justify the very system of juristic reasoning (ijtihad) that produced it. Legal scholars cite this prophetic tradition to validate their authority to create legal rulings – but the tradition itself appears to emerge from that same juristic system. The timing of this hadith’s appearance in the historical record is revealing:

Abd al-Razzaq (d. 211 AH): Serves as transmission common link for Bundle 1

Malik (d. 179 AH): No mention despite comprehensive Medinan legal compilation

Al-Shafi’i (d. 204 AH): Cites it prominently in Kitab Jami’ al-‘Ilm

The hadith emerges precisely during the 25-year window when legal theorists like Al-Shafi’i were systematizing usul al-fiqh and needed prophetic justification for judicial reasoning. Yazid’s note about seeking confirmation from Abu Bakr ibn Hazm appears suspicious rather than authenticating:

- Why would an authentic tradition require such verification?

- This resembles someone testing whether their created hadith would be accepted by established authority

- The added “Abu Salamah → Abu Hurayrah” chain conveniently provides Companion-level authentication

- The corroboration story may be a literary device designed to create authenticity rather than evidence of it

This hadith appears during a crucial period in Islamic legal development. By the late 2nd/early 3rd century AH, Islamic law had evolved into complex systems of juristic reasoning. Scholars needed religious justification for their methodology, particularly the controversial practice of ijtihad – making legal rulings based on scholarly opinion where texts were silent. Rather than acknowledge the human origins of their legal methods, jurists created prophetic traditions that provided divine sanction for their practices. This hadith perfectly serves that function by: Making judicial reasoning a religiously meritorious act, protecting judges from criticism when they err, and providing divine authority for human legal interpretation.

The evidence strongly indicates this hadith was fabricated in the late 2nd/early 3rd century AH to provide religious justification for the developing system of judicial reasoning. The impressive Medinan transmission chains were likely constructed to give authority to what was actually a later juristic innovation. This represents a textbook case of how human legal opinion became disguised as divine command through fabricated prophetic authority. The pattern is clear:

- Legal doctrine develops through human reasoning

- Religious justification becomes necessary for acceptance

- Prophetic traditions are created with prestigious isnads

- The human origin is obscured behind divine authority