One of the most debated doctrines in Sunni Islam is naskh (abrogation), the belief that some Quranic verses cancel or replace others. Classical scholars like al-Suyuti devoted entire sections of their works to identifying “abrogated” verses. Yet, when we examine their lists, the contradictions become apparent: what one authority calls mansūkh, another considers fully valid.

This leaves us with a fundamental dilemma: if abrogation is real, no one can know for certain which verses are valid and which are not.

Suyuti’s Position

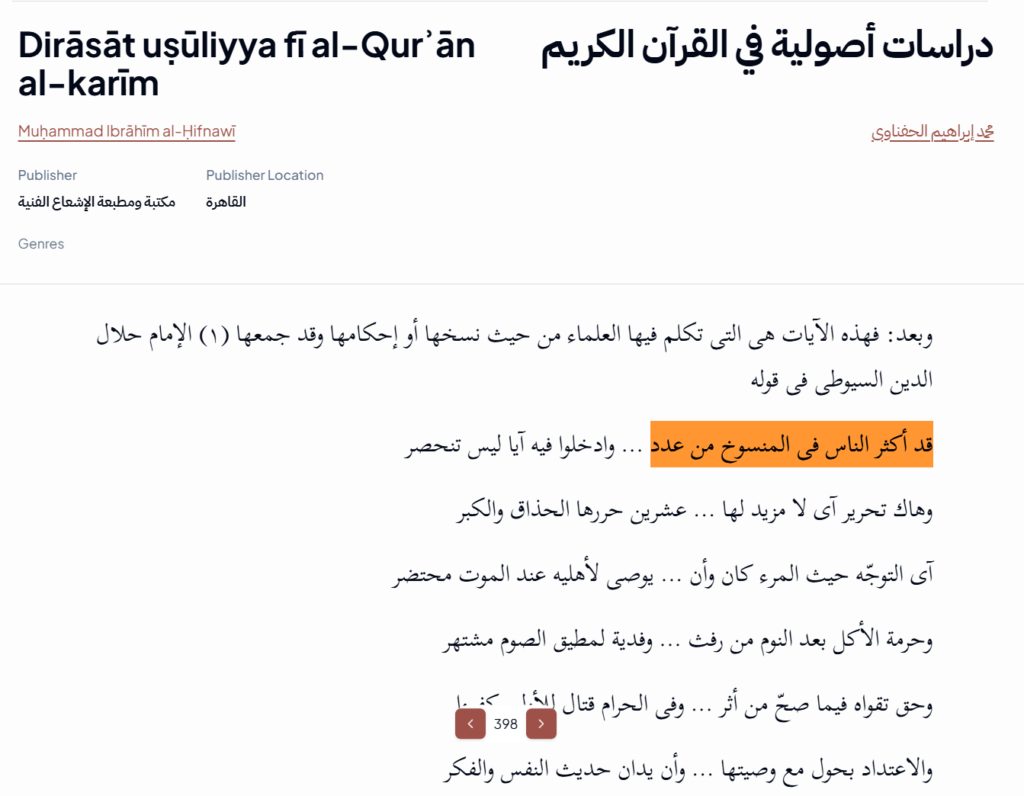

In his famous encyclopedic work Al-Itqān fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, al-Suyuti summarized the issue of abrogation. He acknowledged that earlier scholars had exaggerated the number of abrogated verses, with some claiming over two hundred. To bring order to the debate, he produced a list of about twenty verses that he regarded as genuinely abrogated.

Suyuti even expressed this in a short poem:

People have greatly multiplied the number of “abrogated” verses,

And have included in them verses beyond all count.So here you have a refined list of verses, with nothing beyond them —

Twenty in total, compiled by the experts and masters.The verse about facing the direction (of prayer) wherever one may be,

And that a dying person should make a bequest to his heirs.The prohibition of eating after sleep during fasting,

And the expiation for one who cannot fast, well-known.The command to have true reverence for God (taqwa) as authentically reported,

And the command to fight those who committed disbelief first in the Sacred Months.The requirement of waiting a full year (for widows) along with her bequest,

And that one should be held accountable for inner thoughts and reflections.The command to swear oaths, imprison the adulterer, and the dropping of

Testimony of those who disbelieved, and the commands of patience and going forth (to battle).The prohibition of marrying an adulterer or adulteress,

And that there is no blame upon the Prophet concerning marriage restrictions.The command to pay the dowry to the woman who came (to offer herself),

And the verse of private consultation (najwa).And likewise, the command to stand for night prayer as it was written.

And the addition of the verse about seeking permission concerning those whom the right hand possesses.

Source: Dirāsāt uṣūliyya fī al-Qurʾān al-karīm

Ibn al-Jawzi’s Position

Ibn al-Jawzi authored a dedicated work on abrogation titled “نواسخ القرآن” (Nawāsikh al-Qur’ān), in which he listed the verses he considered abrogated. While the exact number and list can vary depending on manuscript and edition, it is well established that Ibn al-Jawzi did believe in the concept of abrogation and enumerated specific verses. Ibn al-Jawzi is cited as saying:

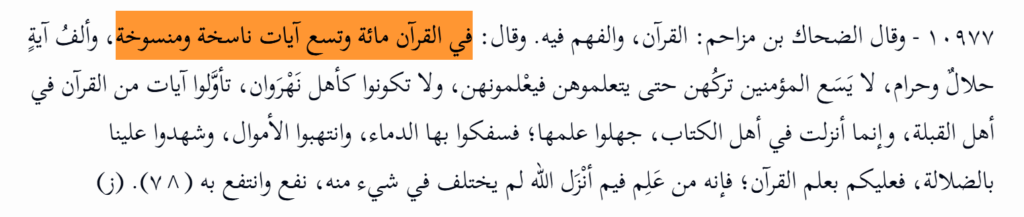

“وقال: في القرآن مائة وتسع آيات ناسخة ومنسوخة، وألف آية حلال وحرام، لا يسع المؤمنين تركهن حتى يتعلموهن فيعلمونهن…”

Translation: “He said: In the Quran there are 120 abrogating and abrogated verses, and a thousand verses of lawful and unlawful, which the believers must not neglect but must learn and teach…”Source: Mawsūʿat al-tafsīr al-maʾthūr – ١٠٩٧٧

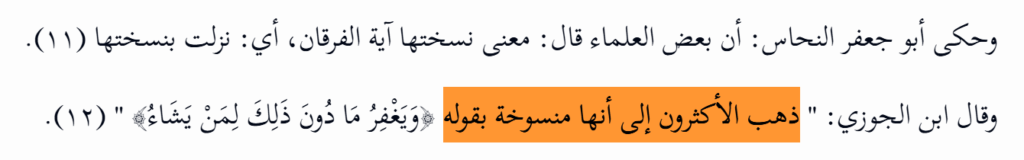

Ibn al-Jawzi often presented both the majority view and dissenting opinions for each verse, sometimes siding with the view that a verse is not abrogated, depending on the evidence and context. For example, regarding the verse ﴾ويغفر ما دون ذلك لمن يشاء, Q 4:48﴿, he wrote:

“ذهب الأكثرون إلى أنها منسوخة بقوله ﴿ويغفر ما دون ذلك لمن يشاء﴾. والثاني: أنها محكمة. وهذا قول أبي هريرة، وابن عمر، وأبي سلمة، وعبيد بن عمير، والحسن، والضحاك، وقتادة، واختاره أبو جعفر النحاس…”

Translation: “Most scholars considered it abrogated by the verse ﴾ويغفر ما دون ذلك لمن يشاء﴿. The second opinion is that it is not abrogated, and this is the view of Abu Huraira, Ibn Umar, Abu Salama, Ubayd bin Umair, al-Hasan, al-Dahhak, Qatadah, and it was chosen by Abu Ja’far al-Nahhas…”The Alleged Abrogated Verse – [39:53] Proclaim: “O My servants who exceeded the limits, never despair of GOD’s mercy. For GOD forgives all sins. He is the Forgiver, Most Merciful.”

The Verse That Allegedly Abrogated 39:53 – [4:48] GOD does not forgive idolatry,± but He forgives lesser offenses for whomever He wills. Anyone who sets up idols beside GOD, has forged a horrendous offense.

Source: Al-Kifāya fī al-tafsīr biʾl-maʾthūr waʾl-dirāya

Other Positions

Abu ‘Ubaid al-Qasim ibn Sallam: He authored “الناسخ والمنسوخ” and is known for a more conservative approach, often listing fewer abrogated verses than Ibn al-Jawzi or Suyuti. His count is generally in the range of a few dozen, though the exact number varies by edition and interpretation.

“فبعضهم عد بضع عشر آية، وبعضهم عد عشرين، وبعضهم رد على ذلك، ولكنه لم يبلغ أقصى ما ذكروه إلا نسبة ضئيلة في المائة”

Translation: “Some counted a few dozen verses, some counted twenty, and some refuted these numbers, but the highest number mentioned is only a small percentage of the total verses”*Abu ‘Ubaid is among those who listed “بضع عشر آية” (a few dozen verses)

Source: Fatāwā al-Shabaka al-Islāmiyya

Al-Nahhas: He wrote a book on abrogation and is mentioned among those who compiled lists, but his number is not always specified. He is grouped with others who sometimes listed “بضع عشر آية” (a few dozen verses) or “عشرين” (twenty verses). The exact number is not always specified, but it is clear he did not approach the high numbers of Ibn al-Jawzi:

“منهم النحاس … وقد تفاوت عدد ما ذكروه من المنسوخ في القرآن، فبعضهم عد بضع عشر آية، وبعضهم عد عشرين…”

Translation: “Among them [are] al-Nahhas … and the number of abrogated verses they mentioned varies: some counted a few dozen verses, some counted twenty…”Source: Fatāwā al-Shabaka al-Islāmiyya

Ibn Hazm: He is also listed among those who wrote on abrogation, but the exact number he gave is not specified. However, he is included in the same group as al-Nahhas and Abu ‘Ubaid, indicating his number is also relatively low and certainly less than Ibn al-Jawzi’s 120:

“منهم النحاس وابن حزم والمقري والكرمي وقتادة وابن البارزي وابن الجوزي…”

Translation: “Among them [are] al-Nahhas, Ibn Hazm, al-Maqri, al-Karmi, Qatadah, Ibn al-Barzi, and Ibn al-Jawzi…”Source: Fatāwā al-Shabaka al-Islāmiyya

Al-Maqri, al-Karmi, Qatadah, Ibn al-Barzi: These scholars are all listed as authors of works on abrogation, and their numbers are described as varying, but always much less than the total number of verses in the Qur’an. They are grouped with those who listed “بضع عشر آية” (a few dozen) or “عشرين” (twenty), and none are reported to have approached the high count of Ibn al-Jawzi:

“وقد ألف في الناسخ والمنسوخ جمع من العلماء منهم النحاس وابن حزم والمقري والكرمي وقتادة وابن البارزي وابن الجوزي… وقد تفاوت عدد ما ذكروه من المنسوخ في القرآن، فبعضهم عد بضع عشر آية، وبعضهم عد عشرين…”

Translation: “Many scholars wrote on abrogation, including al-Nahhas, Ibn Hazm, al-Maqri, al-Karmi, Qatadah, Ibn al-Barzi, and Ibn al-Jawzi… The number of abrogated verses they mentioned varies: some counted a few dozen verses, some counted twenty…”Source: Fatāwā al-Shabaka al-Islāmiyya

The Epistemological Crisis

This isn’t merely an academic curiosity. It represents a fundamental epistemological crisis of knowledge itself concerning the Quran. If abrogation is real and divinely intended, then there should be a clear, reliable way to identify which verses are abrogated. God, presumably, would not leave believers guessing about which parts of His final revelation remain valid. The Quran itself declares that it was sent down as “guidance for mankind” (hudā li’n-nās), but how can it serve as clear guidance if scholars can’t agree on which verses are actually operative? The numbers tell the story starkly:

- Al-Suyuti: ~20 abrogated verses

- Ibn al-Jawzi: 120 abrogated verses

- Abu ‘Ubaid: “A few dozen”

- Others: Various numbers in between

This represents not just disagreement, but disagreement spanning nearly the entire theoretical spectrum. When your most authoritative scholars disagree by a factor of five or more, you’re not looking at minor interpretive differences, but you’re looking at a foundational problem with the entire concept of abrogation. This creates what philosophers would call a logical trap; a situation where all available options lead to problematic conclusions.

Option 1: Accept that abrogation is real, but acknowledge that no one can know which verses are actually abrogated. This makes the Quran’s role as divine guidance fundamentally uncertain. How can believers follow divine commands if they can’t know which commands are still valid?

Option 2: Accept that abrogation is real and that some scholars got it right while others got it wrong. But this raises the question: how do we determine which scholar was correct? What criteria could we use that weren’t available to these classical authorities? And why would God allow such fundamental confusion among His most devoted students? If someone falsely declares a verse abrogated when it is not, wouldn’t that amount to rejecting part of God’s revelation?

Option 3: Reject the doctrine of abrogation entirely. This preserves the Quran’s coherence but requires abandoning a central tenet of traditional Sunni scholarship.

The disagreement over abrogation reveals something deeper than any typical scholarly dispute. It suggests that the traditional Sunni framework for understanding the Quran has a fundamental flaw. If the most learned, dedicated, and pious scholars of the tradition cannot agree on something as basic as which verses remain valid, then perhaps the problem lies not with the scholars, but with the entire framework itself. Al-Suyuti himself seemed to recognize this when he criticized earlier scholars for “greatly multiplying” the number of abrogated verses. But his solution was simply reducing the number to 20, which still leaves us with the same epistemological problem on a smaller scale. How do we know his list is correct when so many other authorities disagree?

The doctrine of naskh was supposed to bring clarity to the Quran. Instead, it has created a situation where believers cannot be certain which verses of their holy book remain valid. Rather than preserving the Quran’s coherence, the abrogation theory has undermined the very certainty it was meant to provide. In the end, the crisis of abrogation forces a difficult question: If scholars this learned and devoted cannot agree on which parts of divine revelation are still operative, what does that tell us about the doctrine itself, and about the broader project of traditional Islamic interpretation?

[6:115] The word of your Lord is complete,± in truth and justice. Nothing shall abrogate His words. He is the Hearer, the Omniscient.

[18:27] You shall recite what is revealed to you of your Lord’s scripture. Nothing shall abrogate His words, and you shall not find any other source beside it.

[78:37] Lord of the heavens and the earth, and everything between them. The Most Gracious. No one can abrogate His decisions.

Keywords:

Quran abrogation, abrogated verses in Islam, Islamic abrogation doctrine, naskh in Quran, Sunni abrogation debate, abrogation of Quranic verses, abrogation controversy Islam, Suyuti abrogation list, Ibn al-Jawzi abrogation, Quran-only perspective on abrogation