The Sunni tradition has great motivation to depict Muhammad ibn Shihab al-Zuhri as a good and trustworthy narrator of hadith from the beginning of his life until the end. He is frequently referred to as a “super-proliferator” of hadith, meaning that countless narrations in the Sunni corpus exist solely on account of him. Weakening al-Zuhri’s credibility changes the status of all the subsequent narrations linked to his chain of transmission and has great implications for the entire hadith literature.

For this reason, later biographers and hadith apologists have a vested interest in portraying al-Zuhri as above political influence, downplaying or outright erasing his decades-long service to the Umayyad court. But the historical record — including testimony from his own students and contemporaries — paints a far more complicated picture. This apologetic framing insists that his proximity to power was incidental, that he “had freedom in the courts,” and that accusations of being a Umayyad agent are based on orientalist misunderstandings or polemical reports. Al-Zuhri was deeply embedded in the Umayyad administrative and ideological apparatus for decades, playing a key role in religious projects that served state interests.

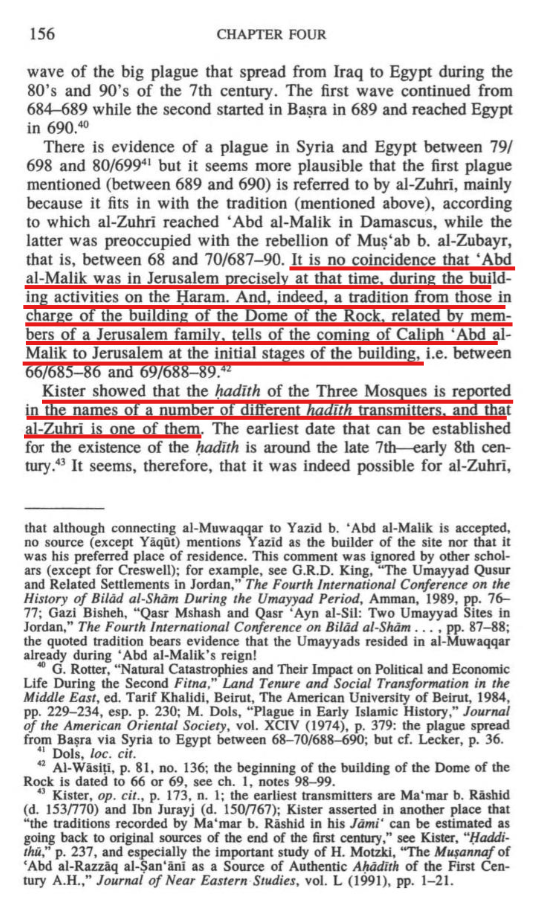

One of the clearest examples of al-Zuhri’s service to the Umayyad political agenda is his role in promoting the sanctity of Jerusalem during the reign of ʿAbd al-Malik. As Prof. Suleiman A. Mourad has shown, this was not an organic development in Islamic piety but a deliberate policy. With Mecca under the control of Ibn al-Zubayr (a rival claimant to the caliphate), the Umayyads sought to elevate Jerusalem as an alternative sacred center. Massive resources were invested in constructing the Dome of the Rock and expanding the al-Aqsa Mosque complex to establish a pilgrimage site firmly under Umayyad control. Al-Zuhri was one of the principal architects of the hadith narratives supporting this policy, including the famous report that only three mosques merit special travel: those in Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem. Michael Lecker, building on Goldziher’s earlier work, notes that al-Zuhri was “given the task of justifying this politically motivated reform of religious life” by attributing such sayings to the Prophet.

The idea that al-Zuhri merely visited the court from time to time collapses when we examine the details of his life. He:

- Served as qāḍī under Yazid II.

- Acted as tutor to Hisham b. ʿAbd al-Malik’s sons.

- Resided in the court city of al-Ruṣāfah for nearly twenty years.

- Dictated hadith directly to caliphal secretaries (sometimes under explicit orders) and allowed Umayyad officials to circulate material in his name without personally verifying its accuracy.

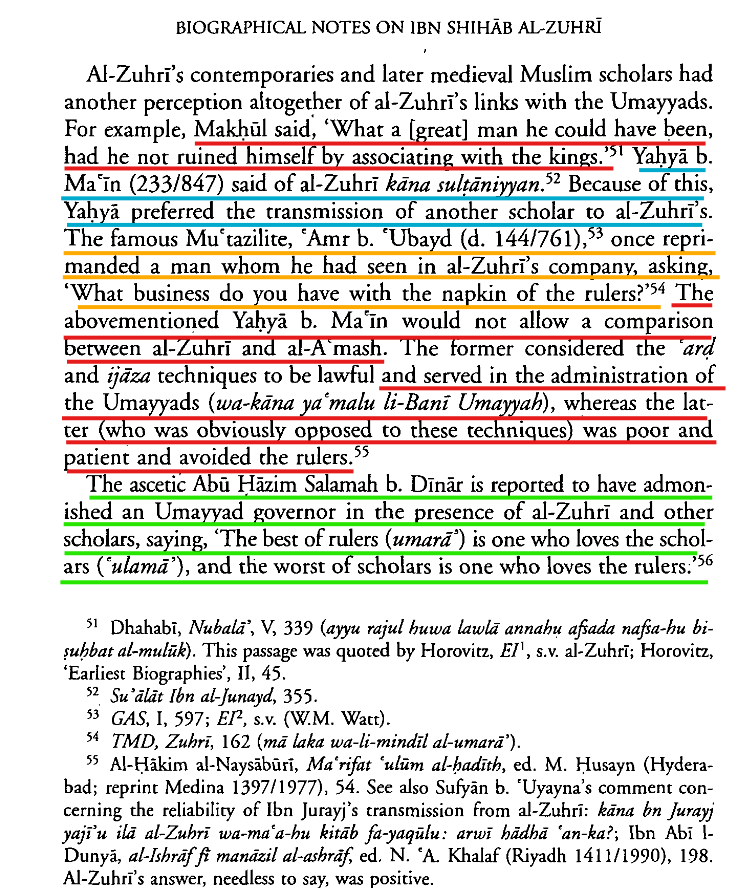

The skepticism about al-Zuhri’s independence is not a modern orientalist invention — it was voiced by respected Muslim scholars in his own era and the generations immediately after. Their words strip away the hagiography:

- Makhūl remarked: “What a man he could have been, had he not ruined himself by associating with the kings.”

- Yahya b. Maʿīn, one of the most respected hadith critics, flatly called him sultānī — “a man of the rulers” — and preferred the transmission of other scholars over his.

- ʿAmr b. ʿUbayd scolded a man for being in al-Zuhri’s company, saying: “What business do you have with the napkin of the rulers?” — a metaphor for being too close to their table.

- Malik b. Anas chastised him for using sacred knowledge to gain worldly advantage.

ON IBN SHIHAB AL-ZUHRI*

MICHAEL LECKER (p. 14)

These were not fringe voices or political enemies. They were leading figures in the transmission and critique of hadith, people who understood both the scholarly and political worlds of their time. Al-Zuhri’s hadith transmission forms a major artery in Sunni isnād networks. Undermining his neutrality doesn’t just tarnish one man’s name, but it calls into question swaths of the hadith corpus that pass solely through him (common link). That is precisely why later Sunni biographers worked to minimize or excuse his long-standing service to the Umayyads. It wasn’t just about defending a scholar’s honor; it was about protecting the perceived stability of the entire hadith tradition.

Why The Cope Fails

Khaleel’s portrayal of al-Zuhri as an essentially independent scholar with only incidental ties to the Umayyads is undermined by the weight of historical evidence. His reasoning leans on a classic fallacy: assuming that because al-Zuhri narrated pro-ʿAli hadith at one stage in his life, he must have maintained that same independence throughout. This ignores the obvious reality that motivations evolve. Al-Zuhri’s career spanned multiple decades, across radically different political contexts — his later life in the orbit of Umayyad power cannot be explained away by citing earlier transmissions from Medina.

The Jerusalem episode alone demonstrates the fusion of politics and piety in his work. When ʿAbd al-Malik needed religious legitimacy for elevating Jerusalem as an alternative pilgrimage center while Mecca was in rival hands, al-Zuhri delivered it. When the caliphs wanted hadith recorded and disseminated through official scribes, he complied; even permitting material to circulate in his name without personally verifying it.

Early Muslim critics recognized the compromises inherent in the approach. Makhūl lamented what he “could have been” without royal association. Yahya b. Maʿīn called him sultānī. Malik b. Anas warned him about using sacred knowledge for worldly ends. These assessments weren’t from anti-Umayyad agitators or modern “orientalists” — they came from within the hadith establishment itself. Recognizing these facts is not an attack for its own sake. It’s a call to evaluate hadith transmission in its historical context, not through the sanitized lens of later hagiography. To continue venerating al-Zuhri as a pillar of Sunni hadith is a theological decision. But to claim his transmission was politically neutral — or to dismiss all contrary evidence as “polemics” — is historically whitewashing him.